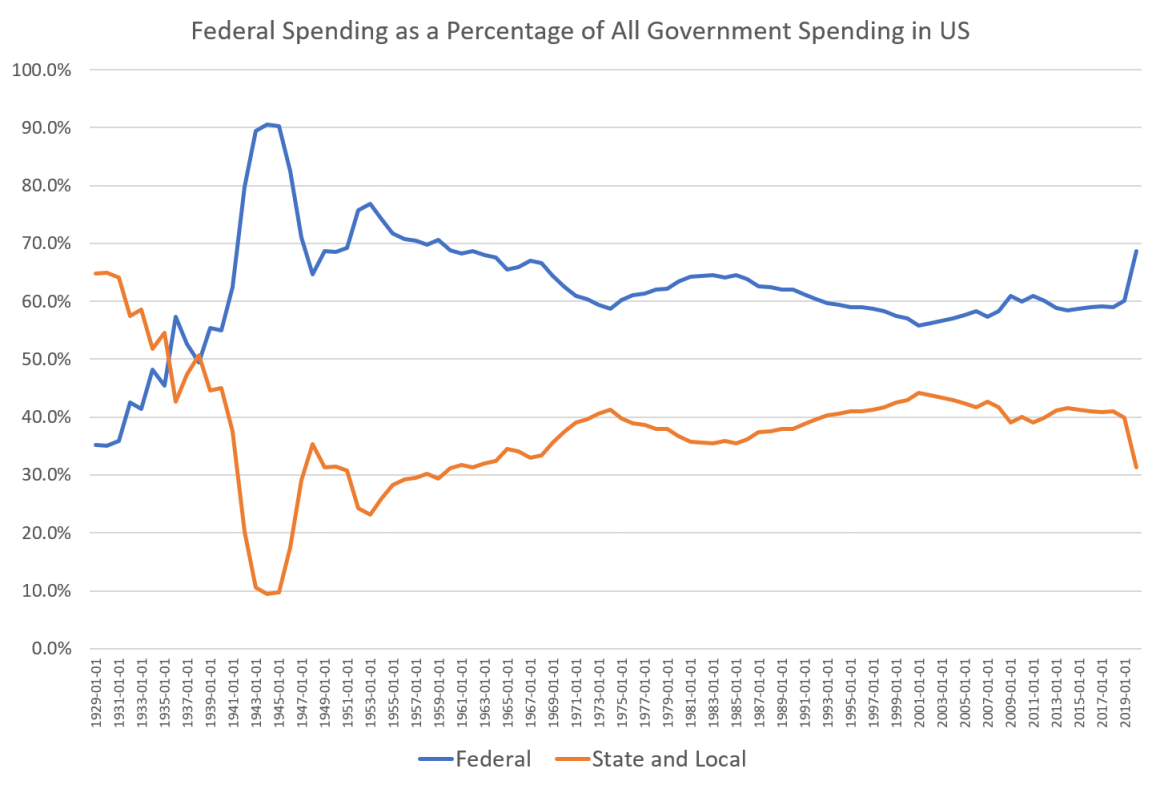

In the wake of the Covid Recession and the drive to pour ever larger amounts of “stimulus” into the US economy, the Federal Government in 2020 spent more than double—as a percentage of all government spending—of what all state and local governments spent in 2020, combined. By the end of 2020, the US’s federal government was spending 68 percent of all government spending in America, while state and local governments spent only 31 percent of all government spending. More specifically, federal expenditures reached 6.8 trillion for the year while state and local spending reached “only” 2.9 trillion. This was a sizable change from the decade leading up to 2020 when the federal government’s share of all government spending tended to hover around 60 percent, while state

Topics:

Ryan McMaken considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

| In the wake of the Covid Recession and the drive to pour ever larger amounts of “stimulus” into the US economy, the Federal Government in 2020 spent more than double—as a percentage of all government spending—of what all state and local governments spent in 2020, combined.

By the end of 2020, the US’s federal government was spending 68 percent of all government spending in America, while state and local governments spent only 31 percent of all government spending. More specifically, federal expenditures reached 6.8 trillion for the year while state and local spending reached “only” 2.9 trillion. This was a sizable change from the decade leading up to 2020 when the federal government’s share of all government spending tended to hover around 60 percent, while state and local spending remained close to 40 percent. The sudden spike to 68 percent pushed the federal share up to the highest it’s been since the 1960s and the Vietnam War. Moreover, from 2019 to 2020, growth in state and local spending nearly flatlined, dropping to 0.38 percent growth over the previous year. That’s the lowest growth rate in state and local spending since 2011 in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Yet, at the same time, federal spending increased by 25 percent. This was the largest year-over-year increase in federal spending since the Korean War. |

Federal Spending as a Percentage of All Government Spending in US, Jan 1929 - 2019 |

A Lot of State and Local Spending Is Really Federal Spending

Yet, these numbers actually understate the extent to which federal spending dominates all government spending in America. This is because a lot of state and local spending is really federal spending, thanks to federal grants.

As noted by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in 2018,

Federal grants to state and local governments help finance critical programs and services across the country. These grants provide roughly 31 percent of state budgets and 23 percent of state and local budgets combined, according to the most recent data.

The share of state spending composed of federal grants varies from state to state with the largest share at 41.9 percent in Michigan, and the smallest in Hawaii at 17.5. Of course, this percentage is driven both by total state spending and by the total amount of federal grants. States that tax a lot and spend a lot in general (e.g., Hawaii, Massachusetts) tend to have a small share of federal spending within their state budgets.

In any case, this is a continuation of a well-established trend. In fiscal year 2011, federal grants accounted for about 25 percent of state and local spending.

So when we’re comparing federal spending with state and local spending, that “60 percent” figure for federal spending over the past decade (as a proportion of all spending) is a low-ball figure.

We should also expect this number to get a lot bigger. Thanks to rising Medicaid costs (mandated by federal law but only partly covered by federal grants) total state spending will increase, but federal grants will rise as well.

In fiscal year 2011, “the federal government provided $607 billion in grants to state and local governments.” By 2019, that figure had risen to $721 billion. My mid-2020, it was clear this total was around $800 billion, and that’s not counting bailout funds and other covid-related funds handed over to state and local governments.

The Role of Deficit Spending and the Central Bank

Perhaps the biggest reason we should expect the federal role to keep getting bigger is because it can do so easily. That is, state and local governments will continue to find it politically difficult to keep raising taxes to cover rising costs. The federal government, on the other hand, has a lot more freedom to spend.

This is because the federal government has much greater access to borrowed funds than state and local governments, and this borrowing process is also subsidized by the US’s central bank.

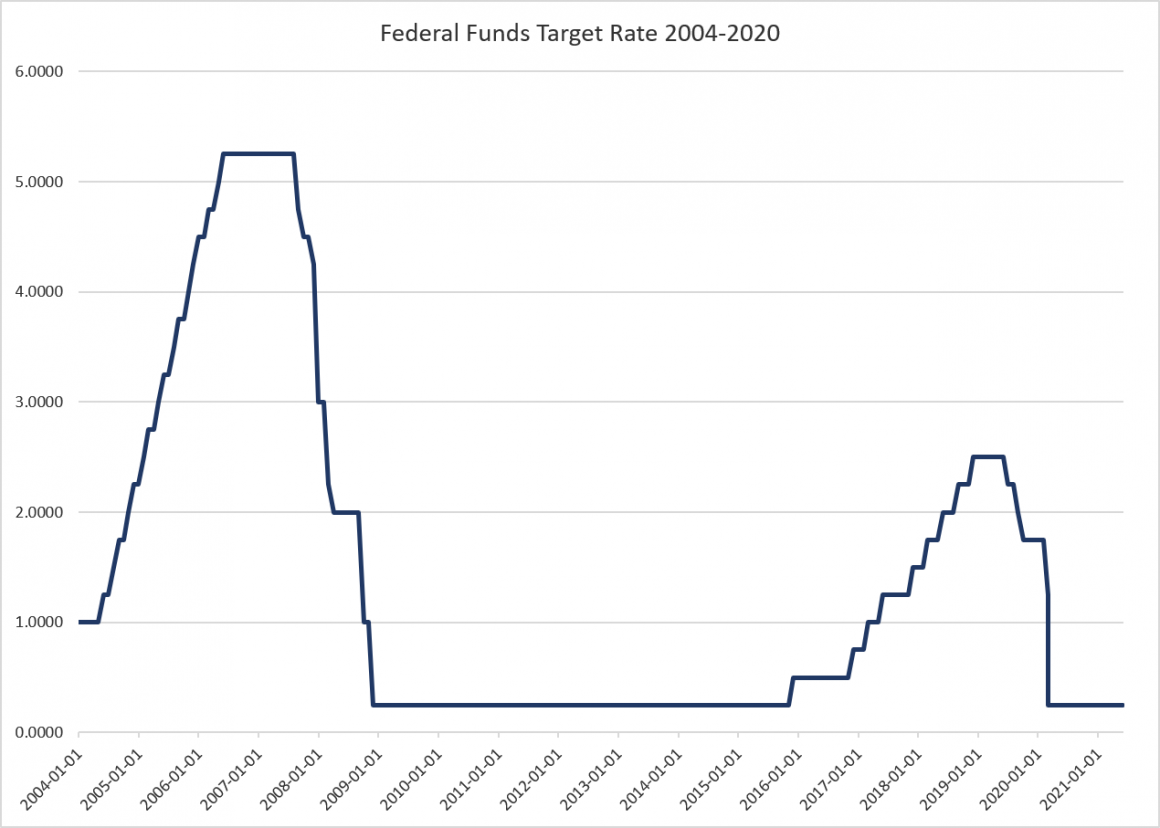

This isn’t normal. In most of the world, and for most state and local governments, rising deficits and mounting debt will tend to lead to rising interest rates and greater difficulty in finding a growing pool of borrowers to take on the government’s debts. The US government, on the other hand, has two things working its favor which allows it to take on trillions in new debts without having to face the realities of rising interest rates: the Federal Reserve, and the status of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

Thanks to the Federal Reserve, when the US government needs to borrow another $500 billion or even another trillion dollars—as has been the case in recent years—the feds need not worry about flooding the debt markets with “too much” debt. Rather, the central bank will swoop in to buy up trillions of dollars in government debt—as has happened since 2008—to ensure that interest rates remain low. The central bank thus prints up trillions in new money in order to put more government debt in its portfolio, essentially monetizing the debt and subsidizing the federal government’s ability to spend.

Of course, if the US were a “normal” country with an ordinary fiat currency, it could never do that. All those trillions of dollars used to force down interest rates on government debt would cause the currency to devalue at catastrophic rates. Things would look more like the situation in Argentina. Fortunately for the federal government and the central bank, however, the dollar remains the world’s reserve currency, partly because the other central banks of the world are at least as irresponsible as the US’s central bank. So, investors and other central banks are still willing to mop up all those extra dollars and store them away.

States and local governments can’t do anything like this. The State of Illinois can’t just spend an extra $100 billion because if it did so, the interest rate it had to pay on its debt would skyrocket. Moreover, even if Illinois had its own currency and a central bank to buy up a lot of this debt, the “Illinois dollar” would not have the benefits of being a global reserve currency.

So, the US’s federal government is in a unique position to keep funds flowing into state and local governments when those governments couldn’t get away with taxing, spending, and borrowing on their own. This means that over time, the federal government will continue to replace state and local tax-and-spend mechanisms with federal spending and federal taxes. It’s just another way that the central bank enables the centralization and growth of political power in the United States.

Tags: Featured,newsletter