The best-case scenario is those who love their “great city” will accept the daunting reality that even greatness can go bankrupt. Two recent essays pin each end of the “urban exodus” spectrum. James Altucher’s sensationalized NYC Is Dead Forever, Here’s Why focuses on the technological improvements in bandwidth that enable digital-economy types to work from anywhere, and the destabilizing threat of rising crime. In his telling, both will drive an accelerating urban exodus over the long-term. Jerry Seinfeld’s sharp rebuttal, So You Think New York Is ‘Dead’, focuses on the inherent greatness of NYC and other global metropolises based on their unique concentration of wealth, arts, creativity, entertainment, business, diversity, culture, signature neighborhoods, etc.

Topics:

Charles Hugh Smith considers the following as important: 5.) Charles Hugh Smith, 5) Global Macro, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

The best-case scenario is those who love their “great city” will accept the daunting reality that even greatness can go bankrupt. Two recent essays pin each end of the “urban exodus” spectrum. James Altucher’s sensationalized NYC Is Dead Forever, Here’s Why focuses on the technological improvements in bandwidth that enable digital-economy types to work from anywhere, and the destabilizing threat of rising crime. In his telling, both will drive an accelerating urban exodus over the long-term.

Jerry Seinfeld’s sharp rebuttal, So You Think New York Is ‘Dead’, focuses on the inherent greatness of NYC and other global metropolises based on their unique concentration of wealth, arts, creativity, entertainment, business, diversity, culture, signature neighborhoods, etc.

The core issue neither writer addresses is the financial viability of high-cost, high-tax urban centers.

It’s telling that Seinfeld’s residency in Manhattan began in the summer of 1976, shortly after the federal government provided loans to save the city from defaulting on its debts and declaring bankruptcy.

In other words, Seinfeld arrived at the very start of New York’s fiscal rebuilding, though its social decline would continue for another few years (the 1977 blackout and looting, etc.). Fiscal conservative Ed Koch was elected mayor in 1977 and by 1978, the city had paid off its short-term debt.

This return to solvency laid the foundation for the eventual revival that attracted capital, talent and hundreds of thousands of new residents, replacing the 1 million+ residents who had moved to the suburbs in the tumultuous 1960s and 70s.

This urban exodus had led to urban decay which had generated a self-reinforcing feedback: the greater the decline in livability, the more people who moved out, which then reduced commerce and taxes, further exacerbating urban decay, and so on.

As I explained in How Extremes Become More Extreme, these feedback loops are one way that Extremes Become More Extreme until a tipping point / phase change is reached and livability and solvency both collapse.

The other dynamic I discuss is the Pareto Distribution, the 80/20 rule which can be distilled to 64/4 (80% of 80% is 64%, 20% of 20% is 4%). Once the vital 4% act, they exert outsized influence on the 64%, far out of proportion to their numbers.

Thus the expanding criminality of the 4% criminal class can dramatically change perceptions of safety and security of the 64%.

Telling people who no longer feel safe in the city that crime only went up 10% will not change their minds.

If 20% of the businesses in a district close for good, the district might retain enough of a concentration of commerce to draw customers.

But once the number of businesses plummets below a critical threshold, the survival of the remaining enterprises becomes doubtful as the customer base drops below the level needed to sustain the remaining businesses.

As I have repeatedly stressed, the surviving businesses are burdened by high fixed costs, none of which have declined even as commerce collapsed.

Again, you cannot persuade people who no longer feel that shopping is safe and fun to get out there and spend, spend, spend like they did a year ago.

Neither Altucher nor Seinfeld mention the macro-issues of demographics and the broader economy.

Despite soaring inflation and a roller-coaster stock market, jobs were plentiful in the 1970s, partly because the Baby Boomers were entering the market for goods and services and partly due to low costs for employers.

Despite soaring inflation and a roller-coaster stock market, jobs were plentiful in the 1970s, partly because the Baby Boomers were entering the market for goods and services and partly due to low costs for employers.

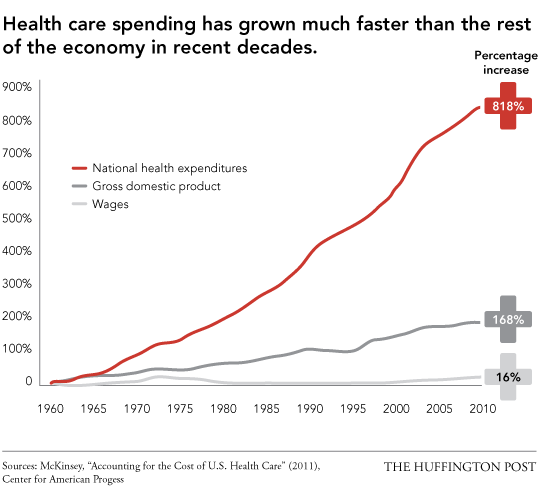

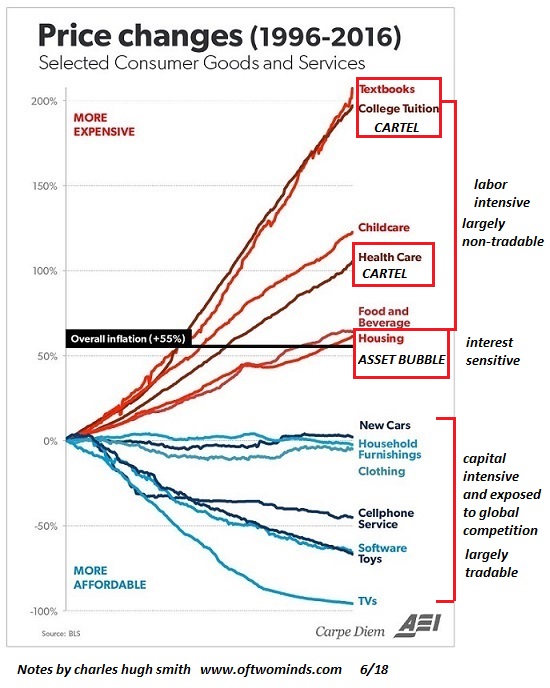

As late as the mid-1980s, it only cost me $50/month (one day’s pay for a moderate-wage worker) to provide good healthcare insurance for a single, young worker. Try buying a month of good healthcare insurance today for one day’s moderate-wage pay.

Not only were rents much cheaper (measured by the number of hours of work needed to pay rent), there were “squats” where the rent was zero, and a variety of cheap “slum” dwelling options. These options have mostly disappeared from the housing inventory, so it now takes enormous sacrifices to live in a “great city”.

Compare these positive demographics and cost structure then to the present. Not only are jobs no longer plentiful, many of the Millennials who flocked to a “great city” for jobs and the amenities can no longer afford to live there.

Many found jobs in the dining-out and retail sectors that have been devastated, and they only survived financially by sharing flats with multiple roommates.

Costs such as healthcare insurance and housing are “sticky:” insurers, landlords, etc. are reluctant to cut prices for fear that cost reductions may become permanent, hurting their profitability.

These high costs are also endangering all the cultural institutions and commercial life that attracted people to the “great cities.” I doubt that every symphony, opera company, museum, music venue, etc. will survive the downturn, due to their incredibly high fixed costs of operation.

As I’ve noted before, the patrons who are financially able to support these costly institutions are older and wealthier, and have the most to lose if they feel their basic security is no longer assured. They’re the first to join the exodus to safer, less risky homes elsewhere. Yes, they’ll miss all the amenities, but not enough to make them stay.

I’ve also stressed the absolute necessity for any entity to be financially viable. If the entity isn’t viable in terms of income covering all expenses, it dissolves regardless of its greatness.

Seinfeld is on solid ground arguing that great cities will never go away, as their benefits are simply too compelling. On the other hand, goats were grazing in Rome’s Forum, a few decades after the Western Empire collapsed.

What collapsed wasn’t just Imperial authority; the city could no longer afford all the free bread and circuses which fed and amused much of its vast populace, not could it defend / maintain the long trade routes that fueled commerce or the political structure that secured the wealth of its nobility.

Cities are not cheap to operate, and they must continually attract workers and capital / wealth which can both be taxed at a high rate. They also need a high volume of commerce that can be taxed.

Most employers are facing a profound reset that will very likely require permanent cost-cutting to maintain profits, and remote work is very cost-effective, as commuting and office space are both unnecessary expenses that can be eliminated.

In terms of financial viability, much of the activity that generated taxes for “great cities” is gone for good: downtown concentrations of tens of thousands of workers that supported hundreds of small businesses, commercial landlords paying high property taxes, and so on.

The question nobody seems to be asking is: are cities no longer financially viable, given the enormous cost of living, the high taxes needed to run the city, and the strong economic and demographic headwinds?

What kind of city is possible if half the small businesses close and tax revenues fall by 50%? What effect will those massive changes have on the livability of the city and its most compelling attractions? How will the city provide services on half the revenues?

The worst-case scenario is only those who can’t afford to leave will be left. Unless great sacrifices are made by those remaining, that’s not a recipe for financial viability, it’s a recipe for goats grazing in the Forum.

The best-case scenario is those who love their “great city” will accept the daunting reality that even greatness can go bankrupt, and that the city will have to adapt in new and wrenching ways to remain financially viable as tax revenues decline and some percentage of the wealthiest taxpaying residents have left or will leave.

It’s not just the urban exodus that’s the challenge–it’s who’s in each successive wave of the exodus. If the wealthy, the entrepreneurs and the displaced small business owners leave in the first wave, the adaptation will have to be rapid and profound, as the modest, incremental reforms that typify the past 75 years will not be enough to be consequential.

Tags: Featured,newsletter