The era of abundance was only a short-lived artifact of the initial boost phase of globalization and financialization. Global corporations didn’t go to all the effort to establish quasi-monopolies and cartels for our convenience–they did it to ensure reliably large profits from control and scarcity. Not all scarcities are artificial, i.e. the result of cartels limiting supply to keep prices high; many scarcities are real, and many of these scarcities can be traced back to the stripping out of redundancy / multiple suppliers of industrial essentials to streamline efficiency and eliminate competition. Recall that competition and abundance are anathema to profits. Wide open competition and structural abundance are the least conducive setting for generating reliably

Topics:

Charles Hugh Smith considers the following as important: 5.) Charles Hugh Smith, 5) Global Macro, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

The era of abundance was only a short-lived artifact of the initial boost phase of globalization and financialization.

Global corporations didn’t go to all the effort to establish quasi-monopolies and cartels for our convenience–they did it to ensure reliably large profits from control and scarcity. Not all scarcities are artificial, i.e. the result of cartels limiting supply to keep prices high; many scarcities are real, and many of these scarcities can be traced back to the stripping out of redundancy / multiple suppliers of industrial essentials to streamline efficiency and eliminate competition.

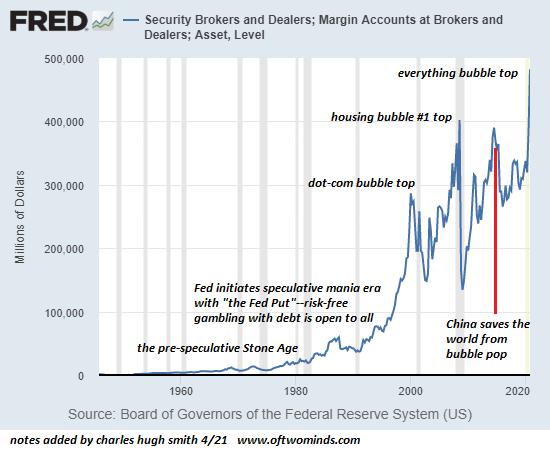

Recall that competition and abundance are anathema to profits. Wide open competition and structural abundance are the least conducive setting for generating reliably ample profits, while quasi-monopolies and cartels that control scarce supplies are the ideal profit-generating machines.

The incentives to expand the number of suppliers, i.e. increase competition, are effectively zero. America’s corporations spent $11 trillion buying back their own stocks over the past decade; that’s equal to the combined GDP of Japan, Germany and Italy. If adding new suppliers to the global supply chain were profitable, some of that $11 trillion would have exploited those vast profits.

The financial reality is attempting to compete with an established cartel that has captured regulatory and political mechanisms is a foolhardy waste of capital. If firing up a new supplier of essential solvents, etc. was so captivatingly profitable, the why wouldn’t Google and Apple take a slice of their billions in cash and go make some easy money?

The financial reality is attempting to compete with an established cartel that has captured regulatory and political mechanisms is a foolhardy waste of capital. If firing up a new supplier of essential solvents, etc. was so captivatingly profitable, the why wouldn’t Google and Apple take a slice of their billions in cash and go make some easy money?

The barriers to entry are high and the markets are limited. A great many specialty lubricants, solvents, alloys, wires, etc. are essential to the manufacture of all the consumer and industrial products that are sourced globally, but the markets are narrow: manufacturers need X amount of a specialty solvent, not 10X.

Back in the good old days before globalization and financialization conquered the world, corporations lined up three reliable suppliers for every critical component, as this redundancy alleviated supply chain chokeholds. But to keep those three suppliers in business, you need to spread the order book among all three. Nobody will keep a facility open if it’s only used occasionally when the primary supplier runs into a spot of bother.

And so now we’re all seated at the banquet of consequences flowing from stripping out redundancy and competition, and ceding control of supply chains to quasi-monopolies and cartels. Scarcities are their source of profits, and since it makes zero financial sense to spend a fortune building a plant to make solvents, lubricants, alloys, etc. in limited quantities in markets dominated by quasi-monopolies and cartels, shortages are a permanent feature of the 21st century global economy.

The era of abundance was only a short-lived artifact of the initial boost phase of globalization and financialization; now that the consolidation is complete, shortages make fantastic financial sense.

By all means thank Corporate America for squandering $11 trillion to further enrich the top 0.1% and insiders. Alas, there was no better use for all those trillions than further enriching the already-super-rich.

Tags: Featured,newsletter