Given the persistent disinflationary pressures in China, monetary policy divergence lends itself to a gradual depreciation of the Chinese yuan against the greenback in 2016 towards 6.70 yuan per US dollar. On 30 November, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) officially decided to make the Chinese yuan (also called renminbi) the fifth sovereign currency in the Special Drawing Right (SDR), joining the US dollar, the euro, the British pound and the Japanese yen in this prestigious basket. The new composition of the SDR will be the following: 41.73% in US dollar (previously 41.9%), 30.93% in euro (previously 37.4%), 10.92% in Chinese yuan, 8.33% in Japanese yen (previously 9.4%) and 8.09% in British pound (previously 11.3%). Some 50% of the weighting was determined by the country's share of exports and the other 50% by financial variables, like the currency’s share in global official reserves. The previous weightings were based on a 60/40 rule. The effective change will not occur until 1 October 2016 with the launch of the new basket. To understand some of the implications of this announcement, it is useful to look more closely at what the SDR is. The role of the SDR The SDR is an interest-bearing international reserve asset created by the IMF in 1969 to supplement other reserve assets of member countries.

Topics:

Luc Luyet considers the following as important: Macroview, Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

Claudio Grass writes Gold climbing from record high to record high: why buy now?

Claudio Grass writes Gold climbing from record high to record high: why buy now?

Claudio Grass writes Gold climbing from record high to record high: why buy now?

Claudio Grass writes The permacrisis strategy: the mortal dangers of our “new normal”

Given the persistent disinflationary pressures in China, monetary policy divergence lends itself to a gradual depreciation of the Chinese yuan against the greenback in 2016 towards 6.70 yuan per US dollar.

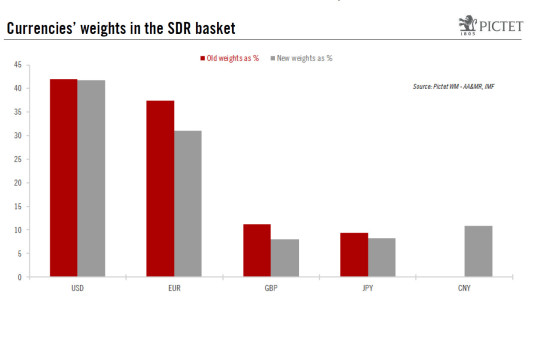

On 30 November, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) officially decided to make the Chinese yuan (also called renminbi) the fifth sovereign currency in the Special Drawing Right (SDR), joining the US dollar, the euro, the British pound and the Japanese yen in this prestigious basket. The new composition of the SDR will be the following: 41.73% in US dollar (previously 41.9%), 30.93% in euro (previously 37.4%), 10.92% in Chinese yuan, 8.33% in Japanese yen (previously 9.4%) and 8.09% in British pound (previously 11.3%). Some 50% of the weighting was determined by the country's share of exports and the other 50% by financial variables, like the currency’s share in global official reserves. The previous weightings were based on a 60/40 rule. The effective change will not occur until 1 October 2016 with the launch of the new basket. To understand some of the implications of this announcement, it is useful to look more closely at what the SDR is.

The role of the SDR

The SDR is an interest-bearing international reserve asset created by the IMF in 1969 to supplement other reserve assets of member countries. It was a response to concerns about the inadequacy between the supply of gold and the US dollar (the two key reserve assets) and the growing demand for international liquidity. However, its birth has not been blessed by a good fairy. Indeed, given the heated debate at that time on the nature of this new reserve asset, the free-of-connotations name “Special Drawing Right” was chosen. More importantly, the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 reduced significantly the role of the SDR, as fears of a liquidity shortage were abated. In practice, holders of SDRs can obtain reserve currencies in exchange for their SDRs. However, as a reserve asset, the composite currency has no obvious advantage compared with the SDR’s constituents, as there are no SDR-denominated bonds or derivatives. Furthermore, except in 2009 when a sharp increase in the stock of SDR (from SDR21.4bn to SDR182.6) was accepted in response to the global financial crisis, there is reluctance among major shareholders in the IMF to increase the SDR supply. As a result, the share of global central bank reserves held as SDRs is low, currently around 3%. Consequently, its main role so far has mostly been to serve as the unit of account of the IMF and other international organisations.

SDR currencies and reserve currencies

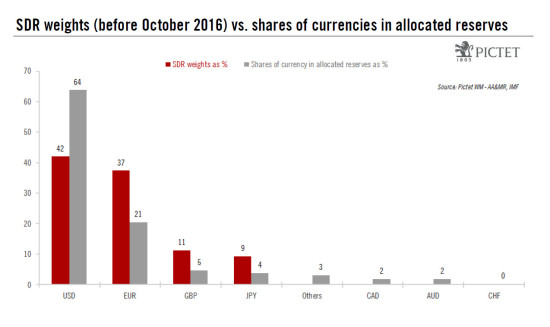

The current criteria to join the SDR basket is that the currency should be issued by members or currency unions whose exports of goods and services need to have the largest value over a five-year period, and to be determined by the IMF as “freely usable”. The latter term does not mean that the currency needs to be either freely floating or fully convertible. As long as it is widely used to make payments for international transactions and widely traded in the principal exchange markets, the currency can be defined as “freely usable”. However, it has to be understood that the currencies’ weights in the SDR do not have a direct impact on the behaviour of reserve managers. For example, while the weightings in the SDR of the British pound and the Japanese yen were 11.3% and 9.4%, respectively, before the inclusion of the Chinese yuan, they only represented 4.7% and 3.8% of global allocated reserves. In practice, central banks consider a currency a reserve asset based on various considerations, notably the existence of a deep and liquid bond market and how fully convertible the currency is. As a result, even if the Chinese yuan has a 10.92% weighting in the new SDR basket to be launched in October 2016, the resulting weight of the Chinese currency in global reserves should likely be lower. If we assume that the Chinese yuan reached 5% of global reserve in a 5-year time window, given that global reserves ex-China amount to around $8tn, this would represent roughly $80bn per year in demand for the Chinese yuan. This is quite comparable to the amount of Chinese yuan that Chinese importers, who need to pay their trading partners in dollars, or Chinese exporters, who get paid in dollars, respectively sell or buy per month. So the inclusion of the Chinese yuan in the SDR is unlikely to have significant implications on the value of the currency in the next 2 to 3 years.

CNY inclusion is just another step in a broader journey

The inclusion of the Chinese yuan is not the end game for China but only a milestone in a broader journey. Indeed, the main objective for China is to continue with financial reforms and to further open up its financial markets to foreign flows. However, recent reforms have been tied to the SDR campaign. In July, China removed all limits on long-term investments of foreign central banks, financial institutions and sovereign wealth funds (other foreign investors are still subject to quotas). In August, following remarks from the IMF, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) eliminated the persistent gap between USD/CNY and its daily fixing, by changing the way the fixing was determined. Finally, in September, the ministry of finance announced its plan to issue for the first time three-month discount bonds, which was necessary as the SDR interest rate is based on three-month instruments. The inclusion of the Chinese yuan in the SDR was therefore necessary to give credibility to these reforms and to push for further liberalisation of its financial market. Coincidently, as China continues to move towards full capital account liberalisation, the Chinese yuan will become a major reserve currency. However, China is likely to walk surely but slowly down that track.

Consequences of the CNY inclusion

As stated earlier, the short-term implications for the Chinese yuan are likely insignificant. For the Chinese yuan to be credible as a reserve currency, further developments in the Chinese financial markets and a more flexible and market-based currency should be necessary. In that regard, it is very unlikely that the PBoC will allow any significant depreciation of its currency on a trade-weighted basis, as it would go against its desire to attract foreign flows into the Chinese capital markets. However, given the persistent disinflationary pressures in China, monetary policy divergence lends itself to a gradual depreciation of the Chinese yuan against the greenback in 2016 towards 6.70 yuan per US dollar. In the longer term, the seal of approval from the SDR inclusion should raise demand for the Chinese currency, especially if China continues to open its capital account. However, while the rest of the world is significantly underweight in Chinese assets, the Chinese people are also significantly underweight in non-China assets. As China pushes further towards full capital account liberalisation, it is still very difficult to estimate what the net change in capital flows will be.