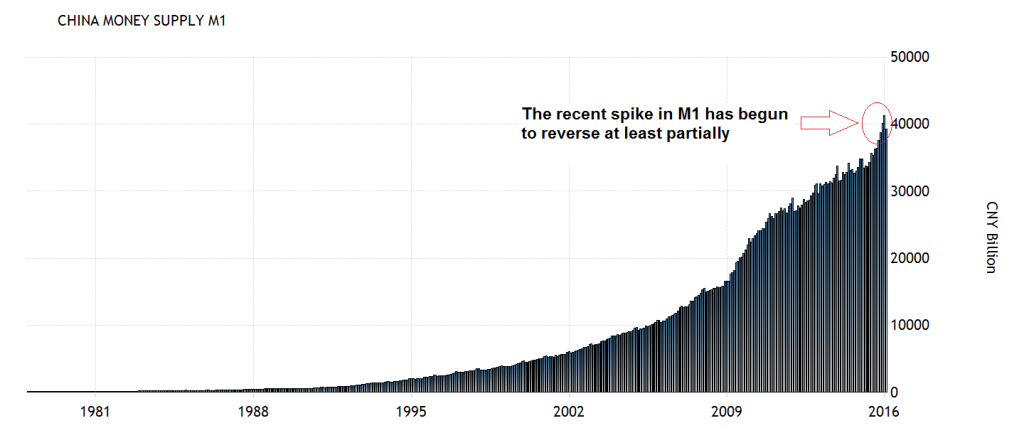

Economic and Demographic Changes We have discussed China’s debt and malinvestment problems in these pages extensively in the past (most recently we have looked at various efforts to keep the yuan propped up). In a way, China is like the proverbial “watched pot” that never boils though. Its problems are all well known, and we have little doubt that they will increasingly find expression. China’s credit bubble is one of the many dangers hanging over the global economy’s head, so to speak. China’s narrow money supply M1 – the money side of the ledger, which is a reflection of China’s enormous credit expansion. The recent spike higher has begun to reverse noticeably in February, with M1 falling back to roughly the level of November 2015 – click to enlarge. However, as we are also fond of stressing, it seems to us that many outside observers are making the mistake of underestimating the strong entrepreneurial spirit of China’s people. In addition, there is a lot of focus on the many ways in which China’s government is faking data to make things appear better than they are (something it has in common with all other governments, only it is more brazen about it), but perhaps not enough focus on what is not known about China’s economy.

Topics:

Pater Tenebrarum considers the following as important: Debt and the Fallacies of Paper Money, Featured, newsletter, On Economy

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Economic and Demographic Changes

We have discussed China’s debt and malinvestment problems in these pages extensively in the past (most recently we have looked at various efforts to keep the yuan propped up). In a way, China is like the proverbial “watched pot” that never boils though. Its problems are all well known, and we have little doubt that they will increasingly find expression. China’s credit bubble is one of the many dangers hanging over the global economy’s head, so to speak.

However, as we are also fond of stressing, it seems to us that many outside observers are making the mistake of underestimating the strong entrepreneurial spirit of China’s people. In addition, there is a lot of focus on the many ways in which China’s government is faking data to make things appear better than they are (something it has in common with all other governments, only it is more brazen about it), but perhaps not enough focus on what is not known about China’s economy.

In other words, there may still be components of economic growth in China that are underestimated, simply because the data that are currently available are not comprehensive enough. It is after all a giant country, and in spite of being run by an authoritarian regime, it has in many ways a lot more economic freedom than the regulatory socialist democracies of the West. Economic freedom and slightly deficient statistics are often related, since the main reason for the State to gather such statistics at all is to provide itself with justifications for meddling with the economy.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Sir John James Cowperthwaite, the former governor of Hong Kong, famously refused to even collect unemployment statistics – on the grounds that they would merely tempt the government to meddle with the economy. He was of course 100% correct and Hong Kong’s economic success under his stewardship proved it in spades.

Nevertheless, it is clear that China’s economy is on the verge of profound change, and it is likely that this change will involve a lot of economic pain as it implies that the capital malinvestments and unsound debt amassed in recent decades (and especially since 2009) will have to be liquidated.

One of the things impelling change in China is actually a result of its very success: hundreds of millions of people have been lifted from abject poverty to middle class status. In recent years, wage growth in China has been enormous, and a side effect of this is that China’s days as the global manufacturing powerhouse are now coming to an end.

At least this is true of labor-intensive production activities, which are these days increasingly shifted to South-East Asian countries in which wages remain far lower. Some Chinese companies have even begun to import foreign workers from countries like Vietnam to counter the pressure of rising wages on their bottom line.

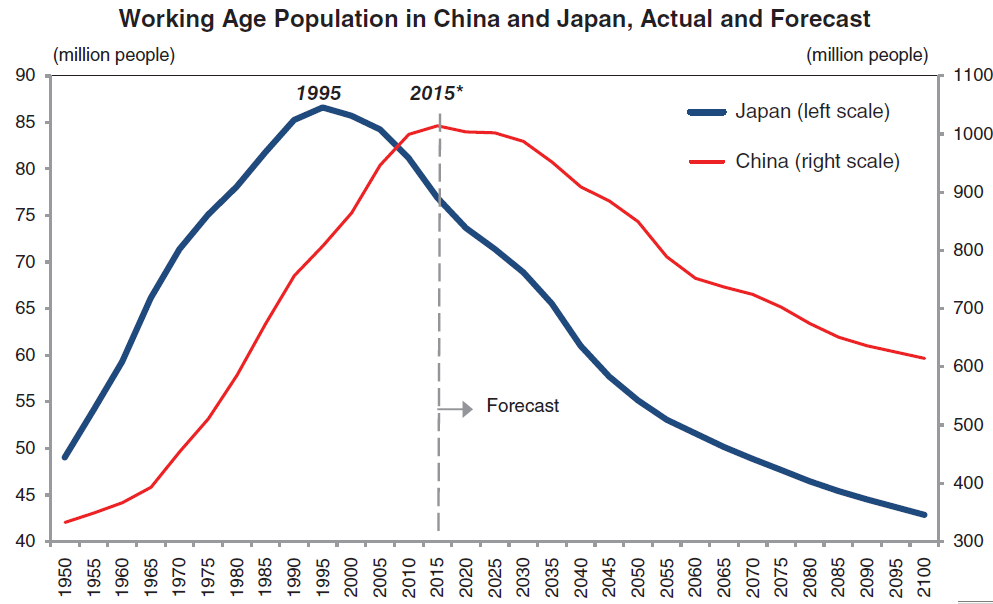

At the same time, China has passed a significant demographic milestone: last year it has joined the world’s “graying societies”. In China’s case this is a lagged effect of the infamous (and utterly nonsensical) “one child policy” adopted by the government in the 1980s. China’s central planners have made the grave mistake of believing the scarcity and overpopulation fear mongers and as a result have created a real problem, one which could have been easily avoided by simply not meddling.

China’s and Japan’s working age population, actual and forecast. In China the inflection point from growth to decline occurred last year – click to enlarge. |

|

Migrating Back to the Sticks

One of the results of the downturn in China’s manufacturing industries is that rural workers who migrated to the cities in their hundreds of millions in recent decades are increasingly migrating back to their rural homes. We don’t think this is all bad, as they are bringing their newly-won expertise back to places that are basically backwaters at the moment and might actually benefit from this influx of know-how.

However, it does have implications for China’s egregious real estate bubble and its countless “ghost cities”. These seem now destined to remain ghost cities, and as such represent the biggest overhang of malinvested capital in all of human history. China has experienced a version of Keynesian pyramid building that truly dwarfs anything that has ever been seen before.

Empty streets and empty high-rise apartment buildings for as far as the eye can see – China’s infamous “ghost cities”. Photo credit: Shane Toms

The Financial Times has recently produced a short video on the phenomenon of older rural workers deciding to leave the cities and going back to their rural homes as job prospects in the manufacturing sector dwindle. The video is entitled “The End of the Chinese Miracle” and not only presents the broader macro-economic perspective, but also shows viewers how individuals are coping with the problem.

As we have noted above, we do not believe this is all bad – after all, change had to happen at some point, and delaying it further would only exacerbate the problems. However, China’s enormous debt and malinvestment bubbles do suggest that this will lead to noticeable economic disruptions with important implications for the global economy.

The End of the Chinese Miracle

Conclusion

One should not underestimate the market economy’s ability to adapt to change. However, this includes the occasional hicc-up, as the mistakes of government intervention need to be periodically corrected. Since modern-day “policymakers” are averse to allowing even the slightest bit of economic pain to materialize (except if the countries concerned are small and helpless, such as Greece), they have implemented unprecedented monetary pumping and debt expansion to hold recessions at bay.

China’s planners have been especially diligent in this respect, misallocating resources in truly grand style and leaving the country buried in a pile of unsound debt. The combination of demographic and economic challenges the country now faces means that more than just a small hicc-up is probably in store, even though the timing of the denouement remains uncertain.

Chart by: TradingEconomics, Richard Koo