Argentina makes press headlines worldwide and tops the inflation world rankings. People are becoming desperate—living in Argentina is extremely tough—and people are beginning to immigrate to foreign countries. The Argentinian peso is, to the world and the Argentinian citizens, a relentless zombie, rejected by the people but supported by the government, which is desperate to snatch whatever money people have left in their pockets. To develop this further, we must go first through the history of the Argentinian monetary system to better understand the current situation. Then we will move to examine this living-dead currency and analyze proposals to return to a prosperous and free society. A Brief Summary of the Monetary History of Argentina The earliest local

Topics:

Octavio Bermudez considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Krypto-Ausblick 2025: Stehen Bitcoin, Ethereum & Co. vor einem Boom oder Einbruch?

Connor O'Keeffe writes The Establishment’s “Principles” Are Fake

Per Bylund writes Bitcoiners’ Guide to Austrian Economics

Ron Paul writes What Are We Doing in Syria?

Argentina makes press headlines worldwide and tops the inflation world rankings. People are becoming desperate—living in Argentina is extremely tough—and people are beginning to immigrate to foreign countries. The Argentinian peso is, to the world and the Argentinian citizens, a relentless zombie, rejected by the people but supported by the government, which is desperate to snatch whatever money people have left in their pockets.

To develop this further, we must go first through the history of the Argentinian monetary system to better understand the current situation. Then we will move to examine this living-dead currency and analyze proposals to return to a prosperous and free society.

A Brief Summary of the Monetary History of Argentina

The earliest local government in the country that today is known as Argentina was established in 1810. Yet it was not until 1861 that the country was unified. Prior to 1881, there was no mandatory monetary system in Argentina. There were few to no laws that regulated or stated how transactions had to be made and which currency had to be used. Moreover, the national government had not issued any national currency for the citizens to use. There was limited circulation of some government-issued money (sometimes not metal backed and leading to inflation), mostly during times of war, and most people used foreign or private currencies. In summary, the system was free (or anarchic).

This state of affairs was put to an end in 1881 when President Julio Argentino Roca established the first national currency with legal tender, the peso moneda nacional, legally binding people to make their contracts in this new gold money. (The 1853 constitution gave the state the faculty of issuing a national currency. However, until Roca it had not been done.) Argentina could not escape economic cycles due to the government regularly injecting fiduciary media to solve its problems. One such cycle led to the panic of 1890. In response, the government created a currency board to stabilize the value of the gold peso called the caja de conversión (the Argentinian gold standard). It was suspended from 1914 to 1927 and abandoned in 1929 due to the global crisis.

In 1931, a year after a Fascist coup, the private Banco Nación (in full, Banco de la Nación Argentina; in English, Bank of the Argentinian Nation), was allowed to issue bank notes without needing to have them backed in gold. In 1935 (during the military-led government) the Banco Central de la República Argentina (or Central Bank of Argentina) was created, a true “bank of banks.” It regulated and supervised commercial banks and credit, accumulated money reserves, and acted as the financial agent of the state. The initial purpose was to tackle economic cycles, but eleven years later in 1946, the bank was nationalized by President Juan Domingo Perón in order to expand the money supply as much as the government saw fit in order to finance its deficit. Thus, the government cared about only one thing from here onward: how much to inflate.

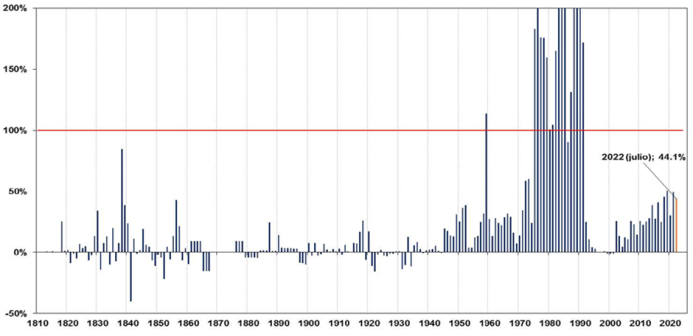

Argentina’s hyperinflation period began in the late ’80s and continued into the early ’90s. This situation was stabilized between 1991 and 2002. President Carlos Menem implemented a system (devised by his minister of economics, Juan Domingo Cavallo) called “convertibility.” It was a currency board pegging the peso with the dollar—one peso to one dollar. Nevertheless, the necessary reforms to support that system were not made, and it was abandoned in 2002 to regain control of the peso and finance the public deficit with inflation. To this day inflation has been increasingly high, and there has been little to no sign that it will decrease in the short- to midterm future. All of this history can be visualized in the graphic below.

Inflation in Argentina, May 1810–July 2022

Source: El proceso inflacionario argentino en el largo plazo (1810–2022) (Santa Fe, Arg.: Bolsa de Comercio de Santa Fe, September 2022).

The Argentinian Peso: A Zombie Currency

There were five different national currencies in Argentina. Yet the inflation problem was never solved. No matter which type of national currency was adopted, inflation continued. Argentinians have historically rejected government money and with good reason. Whoever is in office at any given time always attempts to solve fiscal problems by expanding the money supply.

From the nationalization of the central bank during the first Perónist government to the present day, Argentina has suffered chronic inflation. People abandon the peso for other currencies or goods that tend to preserve their value better than the peso. In this regard Argentina is different from other countries with inflation problems as it would seem to be the only country to have suffered eighty years of chronically high inflation. Saving this zombie money for future consumption is impossible since its value drops massively in the short-term. In April of 2023, year-over-year inflation has been 108.8 percent, and the government is not planning to stop their spending and printing spree.

Politicians insist on maintaining the peso, but Argentinians keep rejecting it because if they don’t, they will lose all their purchasing power given time. The only reason people still use the peso is because the government requires it in order for contracts to be backed by the legal system. Under any economic paradigm the peso is not money; it is a dead currency kept alive by the government by means of force. That’s why the Argentinian peso is neither alive nor dead as a currency but a zombie.

Principles of a Possible Monetary Reform

After examining Argentinian monetary history and analyzing the situation of the zombie peso, the question now is, can anything be done about it? The answer is yes, definitely, but few seem to clearly see the road ahead or have the capacity to do it right. One thing is certain: the peso cannot exist anymore; it must be replaced. A reasonable course of action would be to give legal tender to all currencies for people to spontaneously abandon the peso and use any currency that they see fit (it would seem that the dollar is already the preferred choice for the vast majority). Then all the remaining pesos would be exchanged to dollars, finally eliminating the central bank since it would not be of any use any longer. It looks good on paper, but its application is anything but easy. The monetary reform must be accompanied by a series of economic reforms toward the free market. If not, given time, the dollarization will fail.

No monetary change is possible without slashing public expenditure, deregulating the economy, and cutting taxes. These are necessary measures for anything at the monetary scale to work. If not—as has been noted by eminent Argentinian economists—the monetary reform won’t be accepted by the market since it will be perceived as transitory, ultimately reverting to the inflationist state of affairs.

It must be said that Argentina doesn’t have the necessary dollar reserves to exchange the monetary base for dollars at a reasonable exchange rate—that would be the market rate (net central bank reserves are negative). First the government would increase the dollar reserve to a number between nine and eleven billion, according to one of the most prominent proponents of dollarization, to exchange at market rate (approximately one dollar per 493 pesos as of May 25, 2023). Many proposals are on the table as to how to obtain these dollars. Some are more viable than others, and both ethics and economics have to be taken into account when planning such a policy so neither private property nor the well-being of the people would be harmed.

To conclude, no matter who is in charge next year or whether the ruling party would consider dollarization or not, the administration to be elected by the end of this year will have to deal with this sorrowful situation. Statism or freedom will be their options. There is no place for moderates.

The public opinion is asking for clear positions on concrete issues, and politicians are positioning themselves on either side of the road. Compromisers are being exposed. It would seem that in people’s hearts and minds, liberty rises and socialism falls.

Tags: Featured,newsletter