Own your work. Don’t give it away or let others profit at your expense. Leverage it when opportunities arise. What can The Beatles teach us about management?Young readers may wonder why The Beatles still matter 52 years after the band broke up. It’s a fair question. There are many answers, but perhaps the obvious one (beyond the music, of course) is the band was a cultural phenomenon that has no modern equivalent. A less obvious answer is the unusual dynamics of the four lads: founder John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Paul’s younger mate George Harrison and drummer Ringo Starr (Richard Starkey) who was invited to join the band shortly before they rocketed to global fame. Each had a distinct personality and a unique fan base. Though the songwriting team of

Topics:

Charles Hugh Smith considers the following as important: 5.) Charles Hugh Smith, 5) Global Macro, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Own your work. Don’t give it away or let others profit at your expense. Leverage it when opportunities arise.

What can The Beatles teach us about management?Young readers may wonder why The Beatles still matter 52 years after the band broke up. It’s a fair question.

There are many answers, but perhaps the obvious one (beyond the music, of course) is the band was a cultural phenomenon that has no modern equivalent.

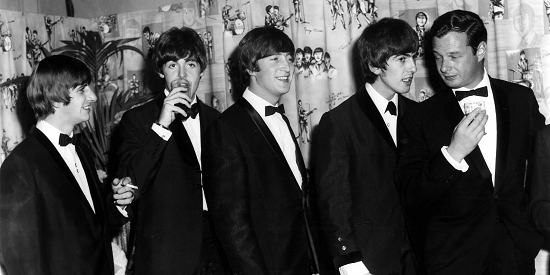

A less obvious answer is the unusual dynamics of the four lads: founder John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Paul’s younger mate George Harrison and drummer Ringo Starr (Richard Starkey) who was invited to join the band shortly before they rocketed to global fame.

Each had a distinct personality and a unique fan base. Though the songwriting team of Lennon-McCartney naturally received the most attention, the band operated by consensus: all four members had to agree on a song for it to be released on a record, and other decisions were also made by consensus: one no vote nixed the deal.

There were other bands with songwriting duos and lively personalities, but none shared quite the same remarkable distribution: there were no “in the background” members in The Beatles.

Due to the intensity of the mania surrounding the band, the members formed bonds which many described in essentially mystical terms: only the four understood their shared experience. Everyone else was an outsider.

As the burdens of fame increased, the band stopped playing live performances and retreated to the studio in 1966. The death of their 32-year old manager Brian Epstein in 1967 left them without a steady hand on the management of the band’s business arrangements, a blow that Lennon realized was devastating. With Epstein gone, the band was in effect managing itself, a task it was poorly prepared to accomplish.

Indeed, the foursome’s own attempt at running their empire, Apple Corps, was soon in such disarray that the band nearly went broke despite their prodigious record sales.

Both Lennon and Harrison had tired of being Beatles by 1966-67, and the group’s sojourn to India in February 1968 marked a transition. The group’s next album (The White Album) was more a collection of solo compositions than collaborations.

By 1969, Lennon’s continued involvement in the band was contingent on the inclusion of Yoko Ono (whom Lennon tellingly called “mother”) in all recording sessions, a move that eroded the unique bond of the foursome.

The coup de grace for the band was the breakdown of decision by consensus: sleazy manager Allen Klein persuaded Lennon, Harrison and Starr into signing him on as manager but McCartney smelled a rat and refused. That was the beginning of the end of the band as an enterprise.

(The three Beatles ended up suing Klein and eventually winning a large settlement.)

Equally interesting from a management perspective are the tug of wars that erupted as the band members matured and the pressures of fame increased. (In 1963 when the band first topped the popular music charts in the U.K., Harrison was 19, McCartney was 20 and Lennon and Starr were 22.)

Unflappable, likeable Ringo had quit the band in 1968 due to feeling unappreciated and left out of the White Album sessions. The other members persuaded him to return.

Unflappable, likeable Ringo had quit the band in 1968 due to feeling unappreciated and left out of the White Album sessions. The other members persuaded him to return.

Harrison famously walked out of a recording session in 1969, Lennon quit in 1969 after the final album recording and McCartney beat the rest to the punch in making the breakup public with the release of his solo album in 1970.

Hard feelings took root and much bitterness was expressed by Lennon and Harrison following the breakup of the band.

Harrison felt that he was unfairly cast as “junior member” in terms of how many of his songs were allowed on each album, and was miffed that Lennon did little to help on Harrison’s songs and McCartney was over-controlling in the studio.

As for Lennon (a mercurial personality, to put it mildly), it seems he resented McCartney’s assumption of leadership, though it was universally acknowledged that Lennon had essentially relinquished any leadership by 1967. He’d worked hard to guide the band to fame (reportedly Harrison had the greatest confidence in their pre-fame days that the band was destined for great things) but lost interest as he wearied of fame and the burdens of being a Beatle.

In contrast, McCartney remained completely committed to The Beatles and responded to the declining interest of Lennon and Harrison by becoming pushier and more demanding, further alienating the other members.

But as Ringo has stated, if McCartney hadn’t pushed, the band’s final records would not have been completed.

While the band’s breakup was a relief to Harrison and Lennon, it was a crushing blow to McCartney, who spiraled into a deep depression fueled by alcohol.

Let’s put on our Manager caps and see who we can recognize:

1. The Founder who’s coasting on past glory but resentful of anyone who takes the reins they’ve dropped.

2. The Over-Achiever who fills the vacuum left by others to keep the operation going.

3. The “quiet one” who isn’t actually that quiet, who resents not being respected for their contributions and being overlooked when it comes to recognition.

4. The easy-going one who gets along with everyone but feels undervalued for being steady, reliable and talented at their job.

5. The con artist who sells snake-oil to the management but fails to con a key manager, and the ensuing conflict breaks what had been a functioning enterprise.

6. Enormous early success that is celebrated at first even as it distorts and burdens everyone involved, eventually driving key members to destructive coping mechanisms (alcohol, drugs, etc.).

7. The manager who rose to prominence in the early days of rapid success but who was left behind as the enterprise no longer needed their particular skillset.

8. The team manages to overcome all their differences and set aside their squabbles for one last brilliant production.

9. Young extremely talented people who mistakenly assume they can manage an enterprise they know little about.

10. The benefits of being a natural at public relations.

11. The benefits of group cohesion.

12. Timing is everything: when the moment is ripe and you’ve put in the work, remarkable things can happen.

There are undoubtedly many others, but the point is The Beatles offer us a microcosm of human interactions and management under great stress and novel challenges. We don’t know what we don’t know, of course, and The Beatles’ experience reflects two truisms:

A. The vast majority of people pitching their services to the very successful are seeking to benefit themselves at the expense of the successful, and should be treated with the utmost skepticism and caution.

B. Recruiting an older, more experienced hand to guide the enterprise who actually has the best interests of the group at heart is often the difference between failure / financial insolvency and stability / financial security. Such people are rare but they do exist.

For all that he did right, Brian Epstein lacked the experience to leverage The Beatles’ enormous early success. The rights to their original compositions were botched, as were merchandizing rights and record sales royalties.

These beginner’s mistakes cost the band millions in income that should have been theirs. These errors were eventually set right but they cost the band dearly.

Good judgment is hard-earned. Manipulative people find young successful creators easy marks, hence the great number of sports and entertainment figures who end up broke despite making millions.

One of the best business decisions the surviving members made occurred 25 years after the band broke up: the release of the Anthology recordings that began in 1995. Their best-selling record, a collection of their 30 #1 songs, was released in 2000.

For me, the lessons are clear: own your work. Don’t give it away or let others profit at your expense. Leverage it when opportunities arise.

Tags: Featured,newsletter