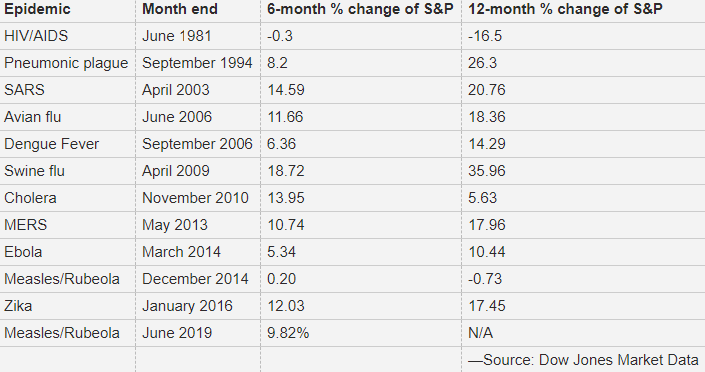

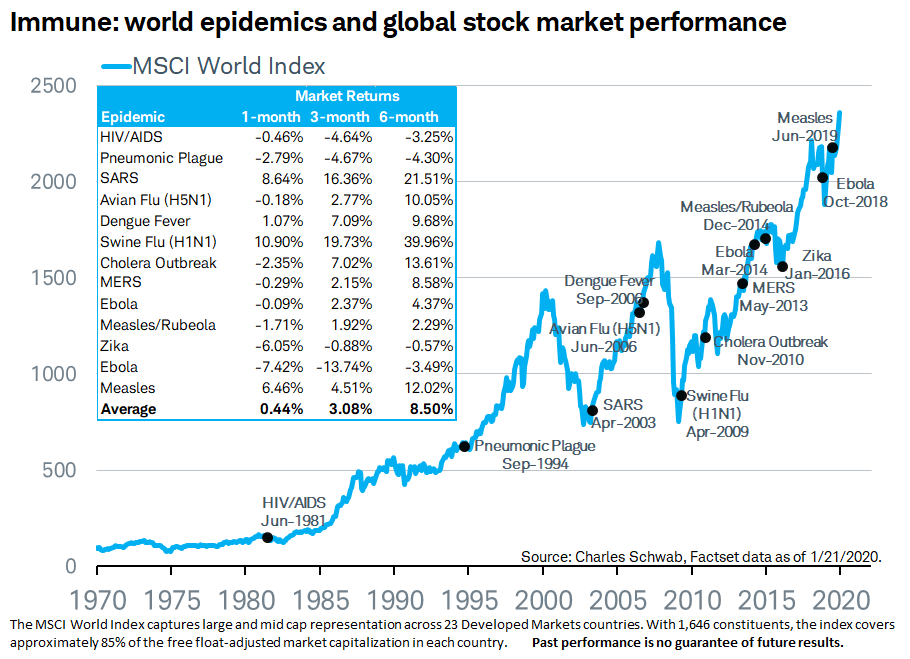

Historically the first two months of a new global virus have been a good opportunity to buy stocks. Markets behave a bit like in a small recession. But recessions is the moment when stock investors make money. Long-Term Profits Decide One should still remember that even if short-term profits decline,only the expected long-term profits finally decide about share prices. And there the virus does not have an influence. Virus Symptoms and Symptoms of Declining short-term Profits via Mark Decambre, Market Watch However, gauged by the market’s performance during the onset of other infectious diseases, including SARS, or severe acute respiratory syndrome, Ebola and avian flu, Wall Street investors may have little to fear that the pathogen will sicken a U.S. stock

Topics:

George Dorgan considers the following as important: Featured, newsletter, Personal Investment

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

| Historically the first two months of a new global virus have been a good opportunity to buy stocks.

Markets behave a bit like in a small recession. But recessions is the moment when stock investors make money. Long-Term Profits DecideOne should still remember that even if short-term profits decline,only the expected long-term profits finally decide about share prices. Virus Symptoms and Symptoms of Declining short-term Profitsvia Mark Decambre, Market Watch

|

|

Epidemics and Stock Markets since 1981

|

|

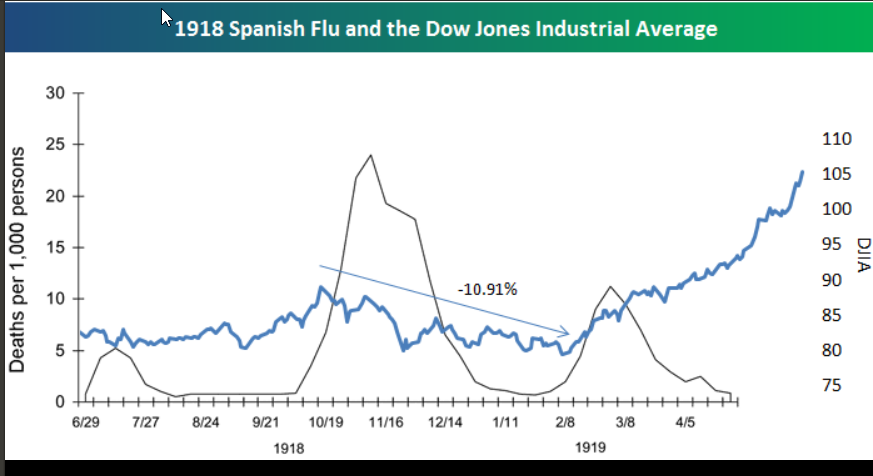

The Spanish FluThe most important global epidemic in the last century, however was the Spanish flu. It killed up to 100 million people. |

|

The Spanish Flu and Stock Markets

|

The 1918 Influenza that highlights deaths per 1,000 people infected with influenza and/or pneumonia, and overlayed a chart of the Dow Jones Industrial Average. There were three pandemic waves from 1918-1919, with the worst coming from October to December of 1918. While fear of the flu was widespread, the market really didn’t react too badly. Following the first pandemic wave, the market sold off a little bit, but then rallied during the summer months before topping out prior to the second wave. The market trended downward during the worst wave of the flu outbreak, but it only went down 10.9% from peak to trough, and then it rallied significantly during and following the third wave. World War I was also coming to an end in late 1918, so the end of the pandemic and the war probably contributed to the subsequent rally in stocks. |

Tags: Featured,newsletter