The Federal Reserve has been on a mission lately to make sure everyone knows they are serious about killing the inflation they created. Over the last two weeks, Federal Reserve officials delivered 37 speeches, all of the speakers competing to see who could be the most hawkish. Interest rates are going up they said, no matter how much it hurts, no matter how many people have to be put on the unemployment line, because that’s the only way to kill this inflation, to save the people from higher prices. They didn’t mention how shifting people from a job to the unemployment rolls would help those people afford the cheaper food, housing, transportation and iPhones the Fed is confident its policies will provide. The big problem with the Fed’s plan to kill inflation by

Topics:

Joseph Y. Calhoun considers the following as important: 5.) Alhambra Investments, Alhambra Portfolios, bonds, Brazil, Chile, commodities, COVID, credit spreads, Crude Oil, currencies, economic growth, economy, emerging markets, energy stocks, Euro, Featured, Fed Funds Rate, Federal Reserve, Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy, GDP, inflation, Interest rates, Inventory, Jerome Powell, Market Sentiment, Markets, Monetary Policy, newsletter, Real estate, REITs, stocks, US dollar, Yield Curve

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

| The Federal Reserve has been on a mission lately to make sure everyone knows they are serious about killing the inflation they created. Over the last two weeks, Federal Reserve officials delivered 37 speeches, all of the speakers competing to see who could be the most hawkish. Interest rates are going up they said, no matter how much it hurts, no matter how many people have to be put on the unemployment line, because that’s the only way to kill this inflation, to save the people from higher prices. They didn’t mention how shifting people from a job to the unemployment rolls would help those people afford the cheaper food, housing, transportation and iPhones the Fed is confident its policies will provide.

The big problem with the Fed’s plan to kill inflation by reducing economic growth and raising the unemployment rate is that those things are not the source of our current inflation problem. People working don’t cause inflation unless they are not creating sufficient supply to meet their own demand. That being the case, one could easily see why too many government workers might be highly problematic. But in the private sector, companies generally don’t hire people who aren’t productive. I’d just suggest that maybe it isn’t the job of the Federal Reserve to determine how many people are allowed to work. Maybe they could help the inflation rate by laying off half – or more – of the 400 economists they employ who don’t produce anything useful. |

|

| It is certainly true that the Fed could hike rates far enough to cause an economic contraction and higher unemployment. And it is also true that in that situation, inflation is likely – but not certain – to come down. But has anyone at the Federal Reserve considered that maybe they could reduce inflation without killing the economy and throwing people out of work? Does the medicine have to kill the patient? Do we have to destroy the village to save it?

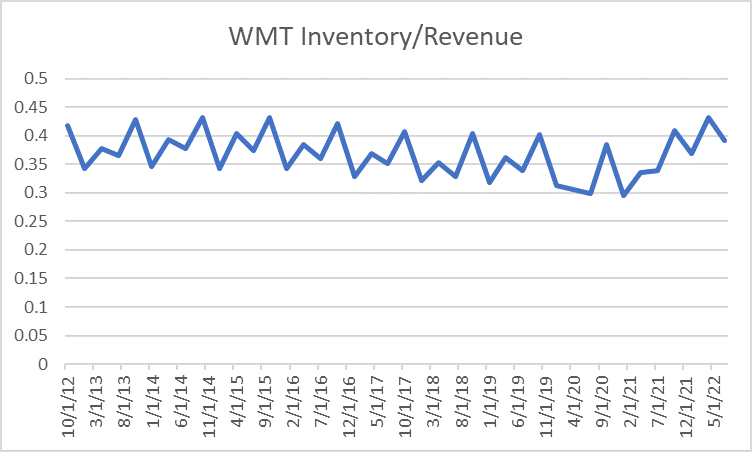

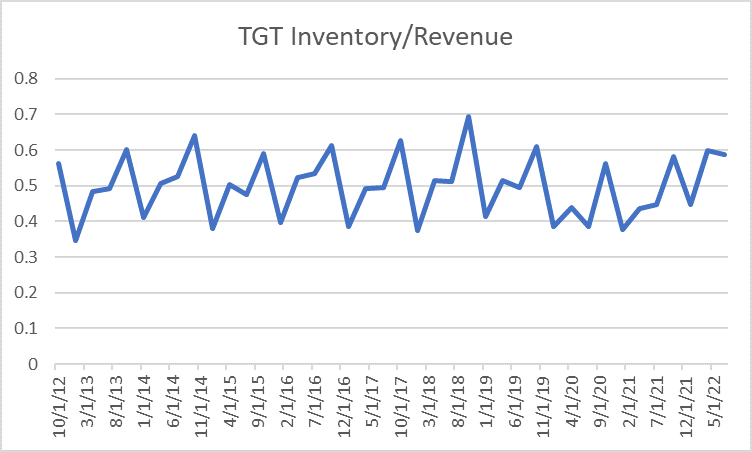

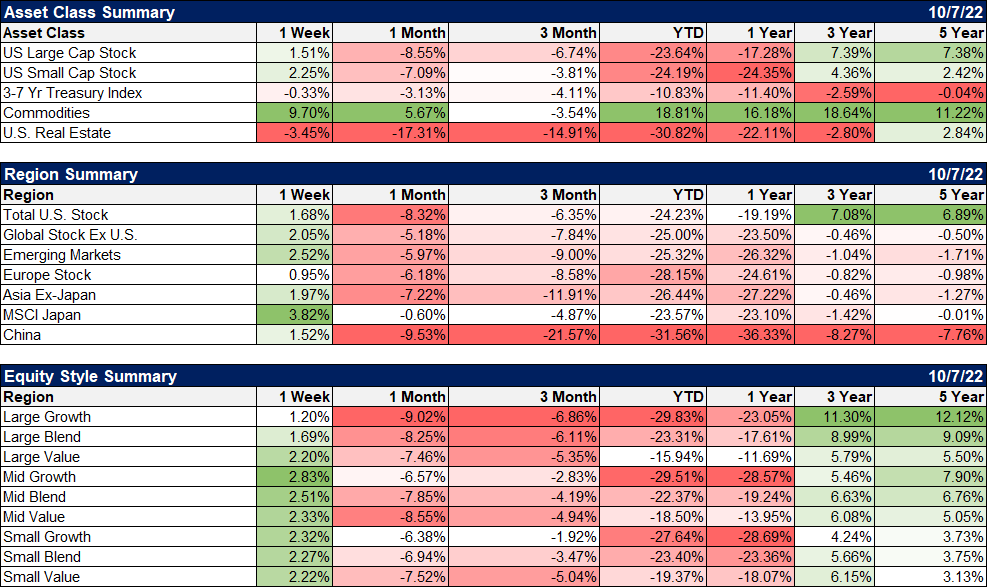

The economy is currently growing despite the Fed’s breakneck pace of rate hikes. How long that will be true with the impact on the interest rate-sensitive parts of the economy is hard to say. Housing is obviously slowing because the Fed’s rate hikes just made buying a house much more expensive (since most people need a mortgage). Auto sales are probably slowing as well based on the number of emails I’ve been getting from auto dealers lately. But other parts of the economy seem to be doing okay and Q3 GDP growth is looking positive (based on the data released so far, growth looks about on trend) after Q1 and Q2 produced little to no growth. Inflation is likely moderating too as we see a plethora of prices fall back to pre-COVID trends. Shipping costs have fallen dramatically although there is some debate about whether that is due to too much inventory or an actual improvement in the supply chain. The answer is likely a bit of both. There are certainly some retailers with too much inventory but as best I can tell, it isn’t widespread and some retailers have done better than others. Macy’s, of all retailers, appears to have managed their inventory in an exceptional manner. But Nike, Target, and Walmart, among others, are having some problems. How big a problem? Not as bad as you might think. Inventory to sales ratios at Target and Walmart are high but not out of the range they’ve been in the past: |

|

| The level of inventories isn’t really the problem. It is a problem of timing; inventory usually peaks in the fall before the holiday selling season. In this case, inventories peaked in the spring. But as you can see the scale of the problem appears manageable.

Other prices that were driven up by COVID, like used cars, are coming back down. We also see it in a number of commodities. Wheat, corn, and soybeans are all well below their peaks. Lean hogs are down although cattle prices still seem a bit sticky. Lumber prices are back down to pre-COVID levels. Copper prices are down by a third. Crude oil hit $130 after Russia invaded Ukraine but it’s down to $92 and has been lower. Natural gas prices are down from a peak of around $10 to $6.75 today. |

That’s still high but exports to Europe are having an impact stateside. Overall, commodity prices are down 14% from their peak but the index has a heavy weight to energy which isn’t down as much as many other individual commodities.

More forward-looking indicators have also improved. The ISM manufacturing survey’s prices paid component peaked at 87.1 in March and has fallen to 51.7 in the September report. That isn’t below the 50 level that would indicate falling prices but it is about average going back a decade or more. The ISM non-manufacturing survey’s prices have also fallen, from just above 84 in April to 68.7 in September. It isn’t surprising that service prices are lagging behind goods prices since the services recovery started later. But the point is the trend is down, the rate of change is falling.

Home prices were already falling in July and that has surely continued with rates up since then. It will take quite a long time for that to show up in the CPI and one can only hope that the hapless Powell knows that. Import and export prices peaked in July as well although they haven’t come down a lot yet. I could go on but the point is made; prices are already coming back down. One might even say that the inflation was transitory; Fed policy hasn’t had time to have much of an impact yet.

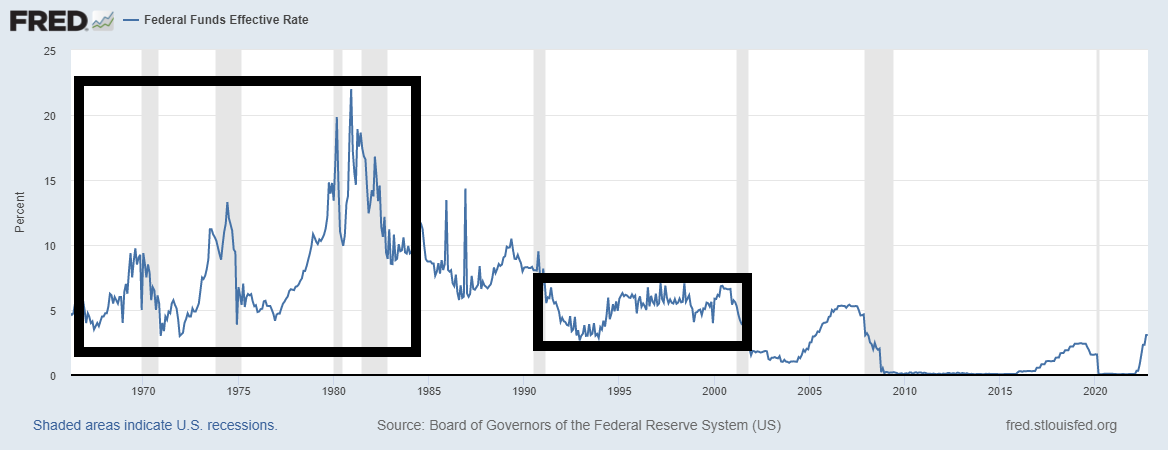

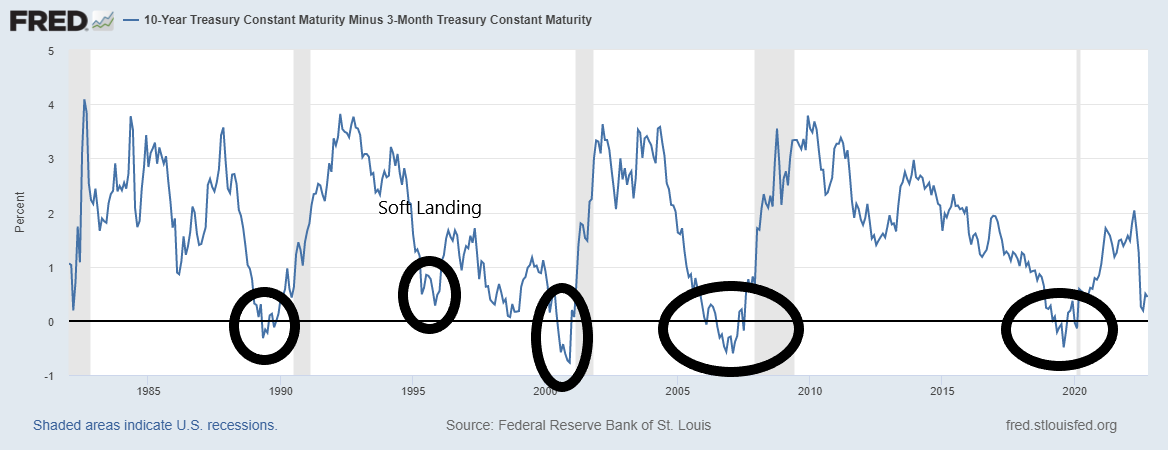

Powell has said previously that backing off rate hikes too soon was a big mistake in the 1970s and he doesn’t want to repeat that. But is it true? Well, maybe, but I think the Fed is drawing the wrong conclusion from the 70s. From December 1968 to August 1969, the Fed raised the Fed Funds rate from 4.0% to 9.75%. In other words, they tightened rapidly. They then had to cut rates all the way back down to 3% in the subsequent recession.

From December 1971 to August 1973 the Fed hiked rapidly again from 3% to over 11% and ultimately to 13.25% in June of 1974. They then cut rates during that recession all the way down to 3% by December 1974. They repeated this rapid tightening, rapid loosening cycle until the Fed Funds rate peaked at 22% in December of 1980.

The logical conclusion here is that the rapid – and large – tightening of policy led to big drops in economic activity that then necessitated a rapid loosening of policy which caused another burst of inflation and a repeat of the pattern. The Fed today seems hell-bent on repeating this mistake. Powell and the other members of the Federal Reserve have said repeatedly in all these speeches that their goal is to raise rates to a restrictive level and hold them there for a long time. If they keep hiking rates at the current pace, they will either create a severe recession or a financial crisis of some kind that ensures they will fail in that goal.

And it is a worthy goal to get rates up and keep them there. Our economy doesn’t function well with interest rates at zero. Higher rates would allow savers to make a reasonable return from low-risk investments and make investing in productive activities more attractive than financial/speculative ones. Higher rates might even convince companies to invest in raising productivity rather than issuing bonds to buy back stock.

We learned – or should have – that going too slow in normalizing rates after a recession can create big problems. Knowing that the rise will be slow encourages speculation, whether in houses or stocks or crypto coins. We should have learned from the 1970s that going too fast also causes problems; the boom and bust cycle was a product of Fed policy.

Monetary policy needs to be conducted in a conservative fashion, with as little change in rates as possible. During Alan Greenspan’s term as Chairman, the Fed Funds rate stayed between 5% and 7% for most of the period from the summer of 1994 to early 2001. Yes, the dot com bubble – if you want to call it that – happened during his watch but I would submit that was more a result of Robert Reuben’s strong dollar policy than Alan Greenspan’s monetary policy. But that’s a great story for another day.

Monetary policy has become unnecessarily complicated over the last two decades. QE and ZIRP and QT and Reverse Repo, oh my. It needn’t be so hard to figure out. In the end, monetary policy is about the supply of and demand for money. The Fed’s job is to keep those two balanced as best they can. I realize they don’t have the control over supply they once did when everything ran through the banking system. But that doesn’t mean they have no control at all.

One of its most potent tools is its communication policy; they can move markets with a well-turned phrase because the market respects their balance sheet. Once upon a time, this ability to influence the market to produce an economic outcome was used sparingly and it was highly effective. That started to change in the early ’00s and today we get 37 Fed speeches in two weeks; Fedspeak has become noise.

To paraphrase Ronald Reagan, the Fed is not the solution to our problems, the Fed is the problem. They introduce volatility to the markets and the economy that have real-world consequences. Consequences, by the way, that the members of the Fed themselves will never face. I can dream about a bunch of economists wandering the countryside, trying to figure out how the real world works, relying on the kindness of strangers for their needs. But it isn’t going to happen.

The solution for the Fed is simple. Talk less, do less. We’d all be better off if we had no idea who Loretta Mester or Christopher Waller or James Bullard were. We’d certainly be better off if we had never even heard of Neel Kashkari. And we might achieve nirvana if Jerome Powell would act more like a diplomat than a soothsayer:

I’m a participant in the doctrine of constructive ambiguity.

Vernon Walters

The Fed needs to pause for the sake of the economy, not the stock market. It needs to pause because not doing so could cause serious and lasting damage to the economy. Unemployment is a malady with effects that last long after the condition is remedied. Jerome Powell and the Fed need to shut up and stand down.

Tags: Alhambra Portfolios,Bonds,Brazil,Chile,commodities,COVID,credit spreads,Crude Oil,currencies,economic growth,economy,Emerging Markets,energy stocks,Euro,Featured,Fed Funds Rate,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,federal-reserve,GDP,inflation,Interest rates,Inventory,Jerome Powell,Market Sentiment,Markets,Monetary Policy,newsletter,Real Estate,REITs,stocks,US dollar,Yield Curve