Macroview In-house simulations of growth impact match those of the ECB PWM has on-boarded the models used in the major central banks to tell us the cost of Brexit for the euro area economy. Using the same models used in major central banks gives our asset allocation policy important advantages. We have the same diagnosis of the situation as the monetary authorities and we are able to enter their mind-set. In the case of Brexit, the challenge has been how to simulate what is essentially a political shock, and how to translate that shock into a proper economic or financial variable. Past events have been helpful in finding a way to do this. The 1992 Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) crisis offered some similarities and insights.Simulations using modelling tell us that the euro area’s real GDP will be reduced by 0.5% after eight to 12 quarters. This is very close to estimates for the cost of Brexit produced by the European Central Bank. This is no coincidence, as we use the latest-generation DSGE model, which has exactly the same characteristics as the models used by the ECB. Economic models such as the DSGE have been workhorses for academics and central bankers alike. These models aim to reproduce the behaviour of different economic agents when confronted with shocks and uncertainty, as well as the interactions between agents.

Topics:

Jean-Pierre Durante considers the following as important: DSGE modelling, ECB forecasts, Macroview, Post-Brexit euro area growth, Post-Brexit growth

This could be interesting, too:

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Big Splits

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Central Bank Halloween

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Widening bottlenecks

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Debt ceiling deadline postponed

In-house simulations of growth impact match those of the ECB

PWM has on-boarded the models used in the major central banks to tell us the cost of Brexit for the euro area economy. Using the same models used in major central banks gives our asset allocation policy important advantages. We have the same diagnosis of the situation as the monetary authorities and we are able to enter their mind-set. In the case of Brexit, the challenge has been how to simulate what is essentially a political shock, and how to translate that shock into a proper economic or financial variable. Past events have been helpful in finding a way to do this. The 1992 Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) crisis offered some similarities and insights.

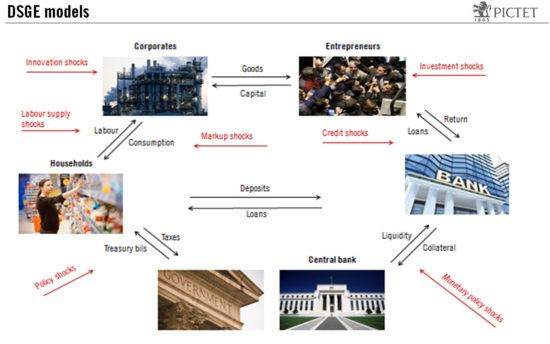

Simulations using modelling tell us that the euro area’s real GDP will be reduced by 0.5% after eight to 12 quarters. This is very close to estimates for the cost of Brexit produced by the European Central Bank. This is no coincidence, as we use the latest-generation DSGE model, which has exactly the same characteristics as the models used by the ECB. Economic models such as the DSGE have been workhorses for academics and central bankers alike. These models aim to reproduce the behaviour of different economic agents when confronted with shocks and uncertainty, as well as the interactions between agents.

The results from DSGE modelling provide us with two very important pieces of information. First, the models tell us that the consequences of Brexit for the euro area economy are not negligible, but not catastrophic either. The models could prove inaccurate, but at least we have the same diagnosis of the situation as the ECB. Second, we are in the same mind-set as the ECB, and so we have precious insights into what could be its reaction to coming events.

In line with the model output, we have revised downward our euro area GDP growth forecast from 1.8% to 1.5% in 2016 and from 1.7% to 1.3% in 2017.