Head of Asset Allocation & Macro Research and Chief Strategist with Pictet Wealth Management, Christophe Donay shares his thoughts on the perennial relationship between innovation and economic growth.When analysing the current economic regime and assessing the potential for a shift in that regime, it is vital to take innovation into account. Demographic trends and productivity gains are commonly identified as the two main drivers of real economic growth. And innovation is a critical contributor to productivity growth. Robert J Gordon, in his masterful study, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, considers that the strong growth performance of the US in the decades that preceded the 1970s oil shock could be mainly explained by a leap in productivity, which in turn was due to innovations

Topics:

Christophe Donay considers the following as important: economic growth, euro area GDP, innovation, innovation matters, Macroview, US economic growth

This could be interesting, too:

Joseph Y. Calhoun writes Weekly Market Pulse: Questions

Joseph Y. Calhoun writes Weekly Market Pulse: It’s An Uncertain World

Joseph Y. Calhoun writes Weekly Market Pulse: Look Up In The Sky! It’s A UFO! Or Not!

Joseph Y. Calhoun writes Weekly Market Pulse: A Fatal Conceit

Head of Asset Allocation & Macro Research and Chief Strategist with Pictet Wealth Management, Christophe Donay shares his thoughts on the perennial relationship between innovation and economic growth.

When analysing the current economic regime and assessing the potential for a shift in that regime, it is vital to take innovation into account. Demographic trends and productivity gains are commonly identified as the two main drivers of real economic growth. And innovation is a critical contributor to productivity growth. Robert J Gordon, in his masterful study, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, considers that the strong growth performance of the US in the decades that preceded the 1970s oil shock could be mainly explained by a leap in productivity, which in turn was due to innovations that had begun to transform the economy way back in the late 19th century such as electricity, the telephone, the railway and the automobile.

However, innovation is often a poorly understood concept in economics. For example, it is important to distinguish between transient and radical innovation. A radical innovation alters the economic system wholescale by changing production processes.

“We believe that we are currently in the midst of a radical technological innovation shock.”

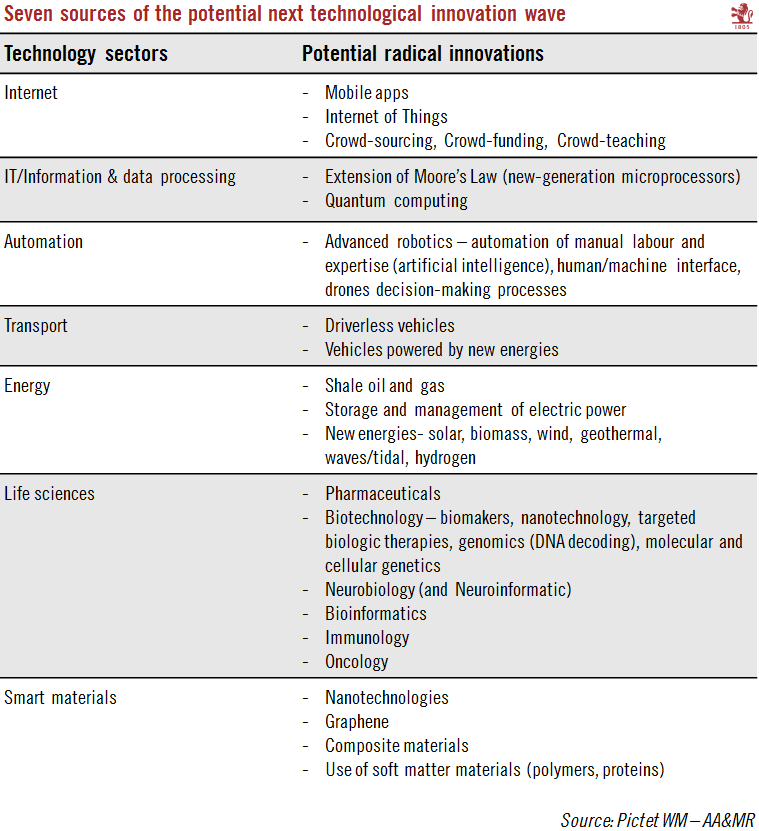

The following chart lists seven sectors which we believe could be sources of the next wave of radical technological innovation. In most of these sectors, US companies account for three-quarters of the top 10 companies by market capitalisation, while European companies account for just 15 per cent and Asian ones for 10 per cent.

Real growth over the last 20 years has averaged nearly 2.5 per cent in the US compared with 1.5 per cent in Europe. As a result, the disposable income of US households has risen 76 per cent more than that of European households over the two decades.

The four characteristics of this radical innovation shock are that it is disruptive, deflationary, global and has exponential effects that should materialise over time. Over seven years after the end of the last recession in the US, it appears we may be experiencing a structural change in developed economies, characterised by continued innovation along with almost full employment – but also by low productivity, high corporate margins and high inequality. The lingering effects of the subprime crisis provide a partial explanation for this situation, but cannot fully account for the continued sluggishness of growth and inflation.

When it comes to consumer prices and wages, the innovation shock, still in its early stages, seems to be adding to the disinflationary pressures that have emerged since the financial crisis of 2008-09. Employment (especially in the US) has become highly segregated between sectors that offer low pay and security on the one hand, and highly paid, highly value added, innovation-led sectors on the other. Technological innovation is exacerbating the income inequalities. Automation is tilting remuneration further in favour of the highly skilled, particularly those working in sectors that provide the technical know-how for the innovation shock, such as IT. But many in the US labour force are not benefiting from this shock. Most job creation is low added value and a large proportion of workers have seen real wages stagnate. Meanwhile, corporate profit growth is becoming increasingly dominated by new economy firms (like Amazon), while traditional players are under pressure (like Walmart).

“The four characteristics of this radical innovation shock are that it is disruptive, deflationary, global and has exponential effects that should materialise over time.”

While there is general consensus around the impact of innovation in terms of wage inequality and polarisation due to the automation of low- and medium-skilled occupations, there is less agreement on the equilibrium impact of new technologies on employment and wages. In other words, and according to Acemoglu and Restrepo in their 2017 paper* on the impact of industrial robots, mere susceptibility to automation does not give the full picture of innovation’s overall economic impact.

The disruption is caused by the innovation shock and deflationary pressures. For the time being, there is little evidence that the current innovation shock is creating much additional activity in aggregate. For example, at a microeconomic level, Amazon has taken trade from traditional retailers (US bookstore chain Borders went bankrupt, for example), but has not actually resulted in any manifest addition to overall household consumption in the US. As its product range expands, Amazon is now also capturing business from other traditional retailers such as Walmart (which recently put part of the blame for a cut in its sales outlook and a profits warning on online competition). But, again, there has been little if any visible addition to aggregate US household consumption data.

For similar reasons, corporate margins remain at record levels. Absent a turnaround in aggregate productivity measures, this regime of low inflation and low wage growth combined with high corporate margins could persist for a while, subjecting some sectors and countries to continued deflationary pressures.

Ultimately, however, stronger wage growth may be needed to trigger an innovation-related investment boom, which would serve to accelerate global growth. If history is any guide, innovation always ends up bolstering prosperity.