As one of Africa’s largest copper producers, it seemed like a no-brainer. Financial firms across the Western world, pension funds from the US or banks in Europe, they lined up for a bit of additional yield. This was 2012, still global recovery on the horizon – at least that’s what “they” all kept saying. Zambia did what everyone does, the country floated its first Eurobond (0 million). At that point, copper was only down modestly from its 2011 peak. By 2014, however, very different story. The Zambian government still needed the dollars, as everyone did and does, and so more Eurobonds. This other one, billion total, was structured by Deutsche Bank as well as Barclays and then further aided by the IMF because of the situation. No need to worry, though, just

Topics:

Jeffrey P. Snider considers the following as important: 5.) Alhambra Investments, China, commodities, Copper, currencies, Dollar, economy, eurodollar system, Featured, Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy, global dollar shortage, lebanon, Markets, newsletter, PMI, Repo, repo collateral, zambia

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

| As one of Africa’s largest copper producers, it seemed like a no-brainer. Financial firms across the Western world, pension funds from the US or banks in Europe, they lined up for a bit of additional yield. This was 2012, still global recovery on the horizon – at least that’s what “they” all kept saying. Zambia did what everyone does, the country floated its first Eurobond ($750 million).

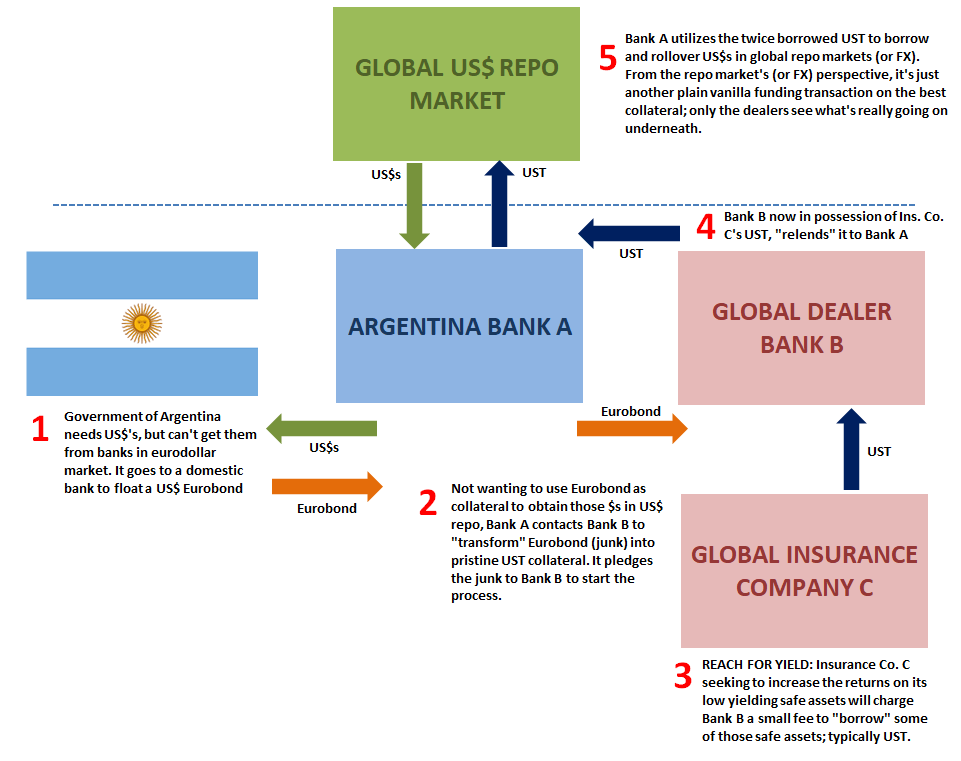

At that point, copper was only down modestly from its 2011 peak. By 2014, however, very different story. The Zambian government still needed the dollars, as everyone did and does, and so more Eurobonds. This other one, $1 billion total, was structured by Deutsche Bank as well as Barclays and then further aided by the IMF because of the situation. No need to worry, though, just “transitory” factors. Further global deflation rather than recovery in 2015, so yet another Zambia Eurobond went out, this time $1.25 billion at a yield approaching double digits. For many nations around the globe, it’s downright painful and dangerous to listen, and keep listening to, the Bernanke’s, Draghi’s, and Yellen’s of the world. This government in Africa had literally bet its country on the inflation story – and now? Zambia has hardly been alone. Though these don’t sound like very big numbers, and they aren’t in the grand scheme of the global dollar shortage, they are enormous for a country in this position and furthermore that’s not the point. We’re seeing first what the eurodollar system always does; it punishes those around the periphery, those riskiest names closest to the dollar precipice. After pushing them over the edge, it works inward toward, well, everyone else. One key reason why, and how this works, these damn Eurobonds. Where do the European banks and American financial firms get the funding to buy them? Where do local African banks who are often the issuer in these situations? Repo. |

Argentina Bank |

| Collateral transformation at the heart of what had been the promise of globally synchronized growth’s increasingly disastrous repo infection. A wide swath of junk collateral whose only hope was ever the inflation story coming true; the so-called commodity super-cycle which had ended in 2011 (Euro$ #2) reignited by…who knows?

Something, something, inflation. Always only ever promises. Instead, Euro$ #4 stepped right in and bludgeoned commodities and commodity countries for another time. Not only did the Eurobond market turn fickle long before 2020 for quite a lot of these places (you might remember Argentina), it turned on its repo users, too. Yeah, that bottleneck in global US$ collateral proved to be the real deal (a taste of which had already appeared starting ~October 2018, or what I call the landmine). But now what? What does Zambia do? What do all the others who are watching a Zambia or a Lebanon with horrified self-interest do? One thing that a lot of them had been doing was turn to Beijing. Its Belt and Road Initiative once popular has become a nightmare, too. The Chinese aren’t exactly swimming in the bucks, either (though you wouldn’t know this year). Instead, they’re constantly asking those on the receiving end to tighten their belt; or else. China doesn’t take prisoners when it can convert defaulted debt into outright ownership. For Zambia, like Lebanon, despite Jay Powell’s post-March 2020 flood of liquidity (he wouldn’t lie about something like that, would he?) those Zambian Eurobonds have tanked all over again. The debt prices had moved higher between April and June, but, like everywhere else around the world, the Eurobonds have sunk all over. Really looks a lot like BRL’s trend after early June. And it’s getting serious. |

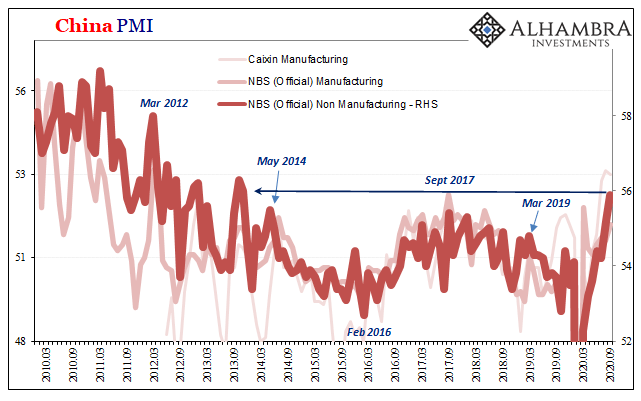

China PMI, 2010-2020 |

Bloomberg reports today:

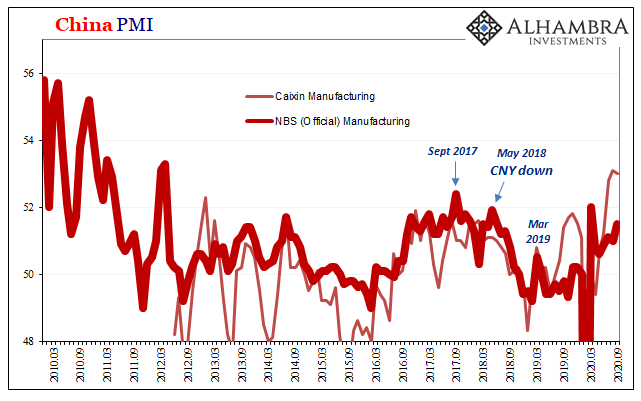

Zambia needs China for more than just possible help getting around this Eurobond bottleneck. Any chance for global recovery especially led by commodity prices is going to have to be a demand rather than supply story. In copper, as the metal has returned to around $3 per pound, and gotten stuck there, it’s largely been because of greatly reduced supply. When it comes to demand, are things really looking up starting where the world needs it; China-wise? |

China PMI, 2010-2020 |

Recent PMI data released early today makes it seem like things are going as predicted; V-like, even. The Chinese government reported its non-manufacturing PMI jumped in September 2020 (55.9) to the highest level since late 2013.

The highest in seven years sounds perfectly awesome, but it’s not. This is the era of huge positives, and this isn’t really a huge positive. Not for a PMI. These numbers suggest the rebound remains sluggish (where are the PMI numbers more like 2010 and early 2011?), and it’s even worse in manufacturing (just 51.5 in September). Don’t take my word for it.

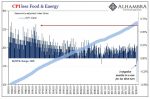

It’s this sluggishness which infects Zambia’s Eurobond prices before then the wider repo position. Why might the dollar remain so unusually, stubbornly high given the reported flood of liquidity from Jay Powell? With that inflationary flood, copper would be flying as global demand for it surged. It’s just not happening; not even to the limited extent of 2017.

Zambia’s problems aren’t just about Zambia; China’s problems not strictly Chinese. Behind all of it, the same structural offshore dollar weaknesses which COVID hadn’t invented, rather it further exposes them.

The global economy continues to rebound; absolutely it does. Is it recovering, though? Even reflating? This shouldn’t even be an issue for September, now October 2020. And there are a whole bunch of clocks ticking down, those on the wrong end hoping beyond hope for an end to the global ambiguity before they do. Gigantic positives or not, this thing’s gotta get going.

Tags: China,commodities,Copper,currencies,dollar,economy,eurodollar system,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,global dollar shortage,lebanon,Markets,newsletter,PMI,repo,repo collateral,zambia