As central banks try (yet again) to bolster faltering growth and inflation, it is important to grasp how the ‘style’ and aims of monetary policy-making have changed over time and how they need to evolve in the future. The world is being disrupted by structural trends such as populism, demographic and climate change and technological innovation. Likewise, with previous approaches producing fewer results, we believe it is time to envisage monetary policies that address these sources of disruption more directly. We observe five different phases of monetary policy making since 1980. Combatting inflation (1980-2008) By far the longest phase saw the Fed push through large, swift increases in the federal funds rate under Paul Volcker. The policy was a success on its own

Topics:

Christophe Donay considers the following as important: 2.) Pictet Macro Analysis, 2) Swiss and European Macro, Central Banks, Featured, Macroview, Monetary Policy, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

As central banks try (yet again) to bolster faltering growth and inflation, it is important to grasp how the ‘style’ and aims of monetary policy-making have changed over time and how they need to evolve in the future.

The world is being disrupted by structural trends such as populism, demographic and climate change and technological innovation. Likewise, with previous approaches producing fewer results, we believe it is time to envisage monetary policies that address these sources of disruption more directly.

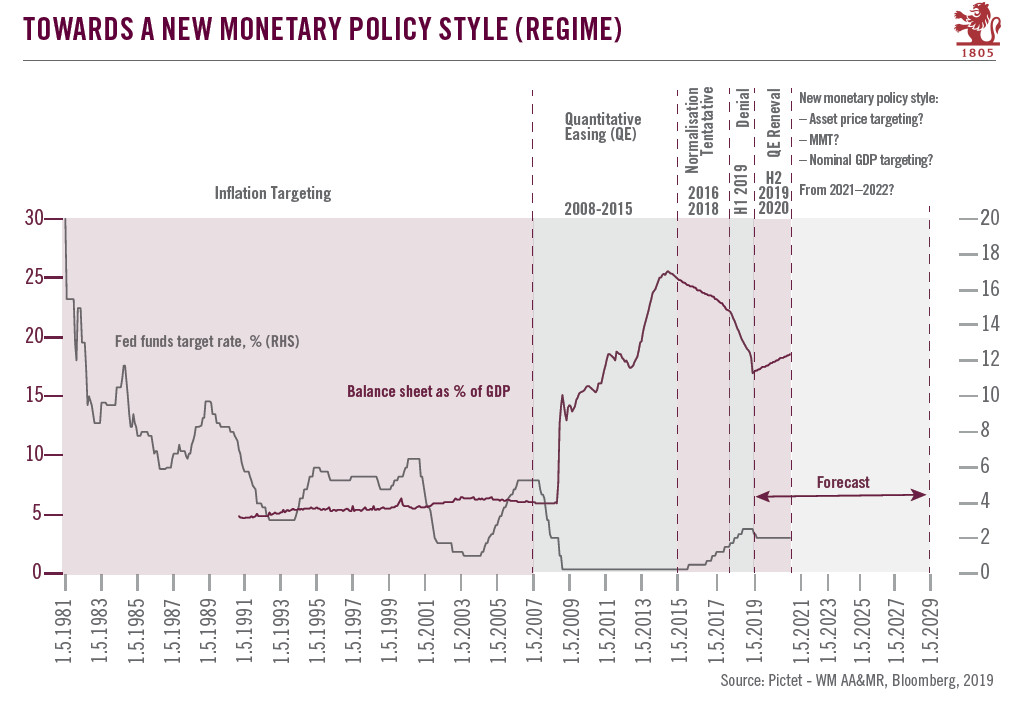

We observe five different phases of monetary policy making since 1980.

|

Towards a New Monetary Policy Style, 1981-2029 |

Deep-seated issues concerning the ends and the means of monetary policy remain unresolved. Central bank mandates will need to be rewritten. Courage will be needed if we are to avoid the excesses of the past and the economic and financial crises that follow in their wake. But central banks need to show they can engage with the issues of today if they are to head off the economic and financial crises of tomorrow. The need to reinvent their mission and set new goals is becoming more imperative.

How successful central banks were in their new mission could determine how far they maintain their independence under their own terms. Finding a way to work with politicians, who have to face an increasingly volatile electorate might be a sensible path forward. The appointment of Christine Lagarde, formerly France’s finance minister, is an interesting move in this respect. Otherwise, there is a risk that central banks become ‘politicised’: the blatant pressure the Trump administration has put on the Fed and its attempts to appoint cronies to the Fed board could be the shape of things to come.

Giving a new sense of purpose to central banks would also require a level of policy cooperation and synchronisation that we have mostly only seen at times of crisis. But such cooperation could help dampen initial market volatility.

A radical departure in monetary policy would initially cause widespread uncertainty in markets. Currencies could depreciate, increasing the attractiveness of physical gold and real assets. A long period of time could pass before central banks regained their credibility among investors, meaning an increase in equity volatility. Overall, markets would have to change the way they look at central banks—no longer seeing them simply as operating the levers of interest rates, but as instigators of social and economic change.

Improved coordination of monetary and fiscal policies will be needed in this exercise. The growing ineffectiveness of older kinds of monetary policy, including QE, combined with public budget plans hamstrung by high indebtedness, could force the political and monetary authorities to find common ground. One might therefore see central banks cooperate more closely with government authorities (but without losing their independence) to combine budgetary and fiscal measures with monetary policy to help create and not just distribute purchasing power. This could involve employing new tools—anything from flexible inflation targeting, to nominal GDP growth targeting to asset-price targeting. Central banks might even explore the option of helicopter money—in other words, distributing money directly to all citizens (and not just banks) to stimulate the economy. The upsurge of interest in modern monetary theory (MMT) points in this direction. Thus, monetary policy could become a part of the solution of inequalities, with the marriage of spending, tax and monetary measures contributing to a new economic policy ‘style’.

Rising inequalities and job insecurity, mass migration and severe environmental challenges—all factors in the surge in populism—are threatening political stability. Since political instability spills into economic and financial instability, might resolving these issues not become one of the central banks’ prime goals? One might therefore imagine a new phase of monetary policy that sees central banks broaden their narrow focus on inflation and growth to include tackling inequalities, for example.

Under these circumstances, we believe that central banks could throw in the towel as growth continues to fade and the limits of further QE become more evident in the absence of strong budgetary and fiscal stimulus. If nothing else, it is hard to see how negative bond yields, in part the result of QE, can be sustained in the long term. The time is therefore ripe to look at setting new central bank goals to contend with the complexity and interconnectedness of today. We believe the debate over goals will lead to the emergence of a new style of monetary policy early in the next decade.

Home-grown dynamics alone will not be enough to prolong the expansionary phase of the business cycle, already the longest ever in the US. This is not only because of businesses’ and governments’ limited capacity to absorb yet more debt, but also because real rates close to or below zero and slowing growth stymie central banks’ ability to ensure extra liquidity feeds directly into the economy (the problem is especially acute in Europe and Japan).

However, there is no guarantee that a new dose of QE will prolong the growth cycle and lift inflation. Previous QE programmes had some success because they were accompanied by ambitious fiscal and budgetary measures, taken under the threat of deflation. However, central banks have singularly failed to lift inflation back towards their 2% target, and growth since 2009 has been below that of previous expansionary cycles. There is also the question of accumulated debt. Theoretically, this could keep growing, but constraints will be increasingly felt. According to the Bank for International Settlements, nonfinancial corporate debt in the US had risen to over 72% of GDP in Q4 2018. Gross federal debt in the US rose to 105% of GDP in 2017 from 82% in 2009.

Tags: central-banks,Featured,Macroview,Monetary Policy,newsletter