Most people have the impression that these various payroll and employment reports just go into the raw data and count up the number of payrolls and how many Americans are employed. Perhaps the BLS taps the IRS database as fellow feds, or ADP as a private company in the same data business of employment just tallies how many payrolls it processes as the largest provider of back-office labor services. That’s just not how it works, though. In fact, sampling and statistical processing first, and then something called trend-cycle (cringe). Benchmarking is in many ways about just this; subjectively estimating the “baseline” economic trend and then for the high frequency data marking up or down any monthly changes from it (I’m oversimplifying on purpose). For employment

Topics:

Jeffrey P. Snider considers the following as important: 5.) Alhambra Investments, benchmark revisions, currencies, economy, employment report, establishment survey, Featured, Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy, FOMC, household survey, jay powell, jobs, labor force, labor force participation rate, Labor market, Markets, newsletter, payrolls, rate hikes, trend-cycle, unemployment rate, wages

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

| Most people have the impression that these various payroll and employment reports just go into the raw data and count up the number of payrolls and how many Americans are employed. Perhaps the BLS taps the IRS database as fellow feds, or ADP as a private company in the same data business of employment just tallies how many payrolls it processes as the largest provider of back-office labor services.

That’s just not how it works, though. In fact, sampling and statistical processing first, and then something called trend-cycle (cringe). |

|

| Benchmarking is in many ways about just this; subjectively estimating the “baseline” economic trend and then for the high frequency data marking up or down any monthly changes from it (I’m oversimplifying on purpose).

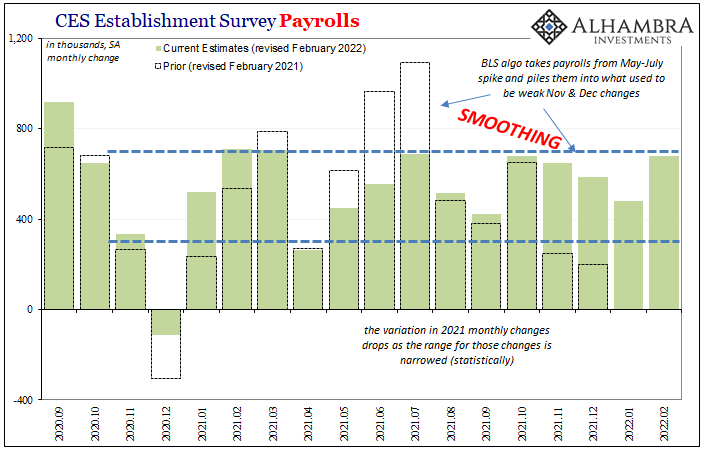

For employment data more than any other type, data providers detest high levels of variations even though, in a high frequency setting, variation is inherent. We live in a complex society operating in a dynamic economic marketplace. That means depending more on something like trend-cycle to “smooth out” the natural lumps. |

|

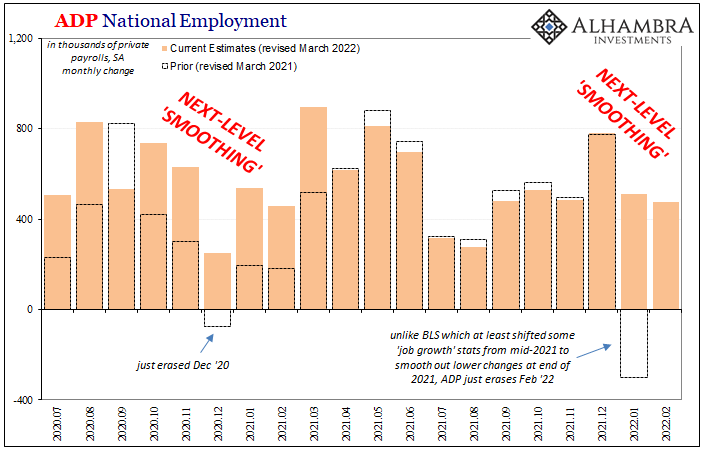

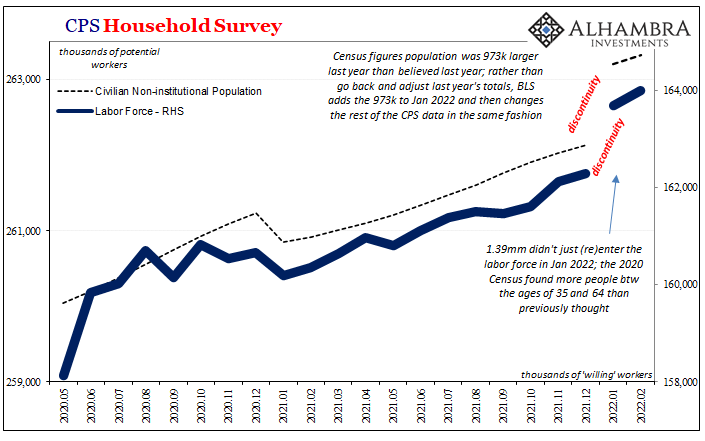

| The BLS only samples state-level unemployment filings (not the IRS) in its annual benchmarking process while ADP falls back on the BLS’s CPS. That’s what happened with the latter’s data for last month, as discussed earlier this week. The Household Survey was riddled with discontinuities because of the 2020 Census, so ADP started from the updated data and basically worked backward in a straight line, in the process erasing pretty much all its prior monthly estimates, particularly any weak months along the way.

Yeah, it’s not exactly counting heads or paychecks. |

|

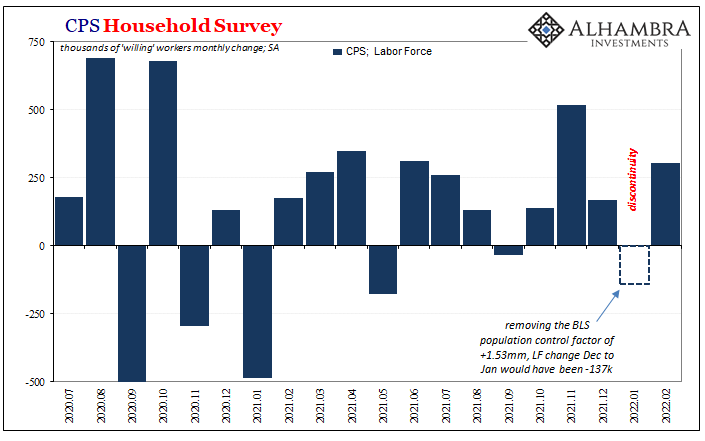

| What this means for the latest payrolls reports covering the month of February is different. Beginning with the CPS and its Household Series, because this is easy, last month’s revisions basically mean we have to start over with January 2022; everything before then just isn’t comparable to the estimates we have now and those going forward. |  |

|

In February specifically, the HH Survey gained 548,000, compared to January’s unknown (the BLS gave a number excluding its population control factor, but who knows). It is in line with other data, so it looks like a pretty solid gain.

The Labor Force added 304,000, getting back some of the workers who might’ve exited (if we use the population control factor) back in January. This appears to be somewhat consistent with slow and incremental additions to the labor force dating back to last year (again, keeping in mind the discontinuity). The Establishment Survey is a bit harder to judge because of the benchmarking. |

|

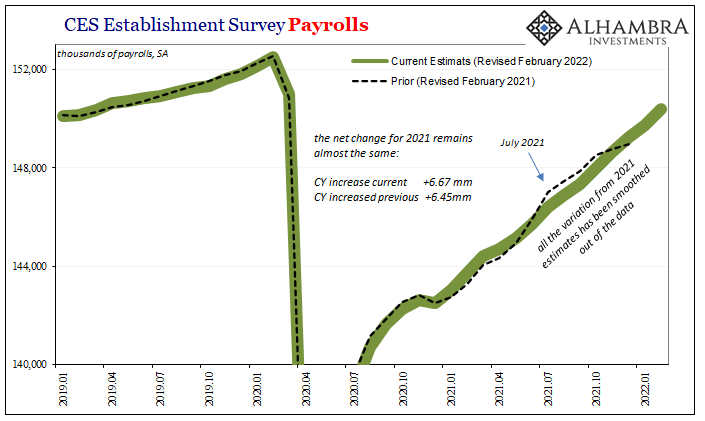

| While there are no discontinuities here, you can see what all that smoothing has done; it has put the series on a steady incline “pegged” to an average of around 500,000 per month (you can see this clearly on the chart immediately below). The February headline payroll number is +678,000, better than that “baseline” and above expectations, while private payrolls were comparable at +654,000.

In other words, by “count” of both surveys while taking account of the data lumps February did, indeed, seem to be a good one in terms of the labor market. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

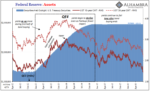

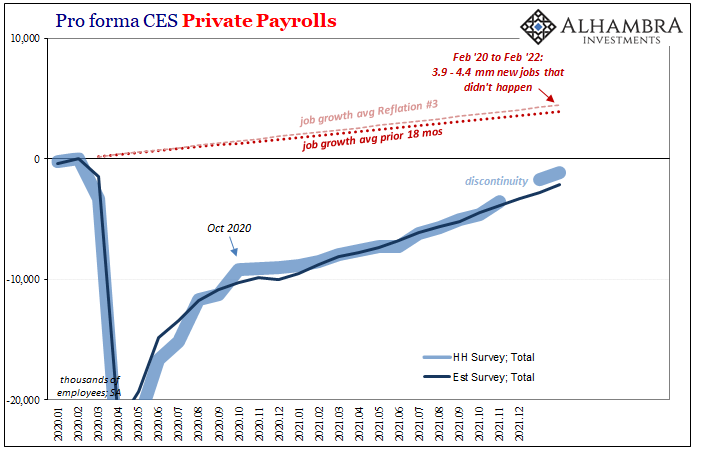

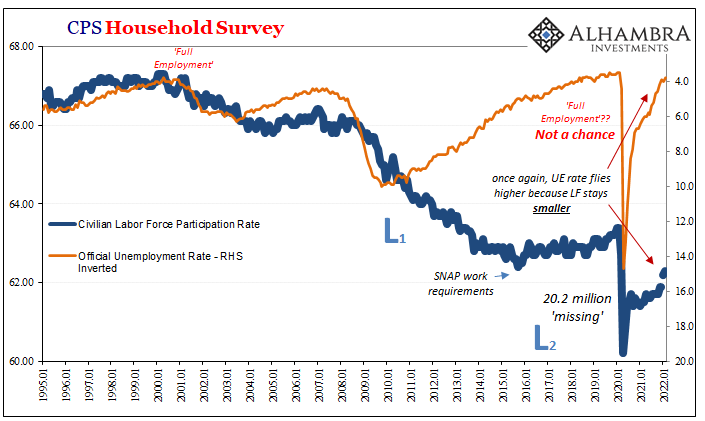

Was it as good as the unemployment rate falling to 3.8%? That may be another question entirely. For starters, the jobs market remains nearly a million and half payrolls (Establishment Survey) short of February 2020 even though the prior peak is now two years in the rearview. More importantly, this does not take account of the 3.9 to 4.4 million “new” jobs that were never created during those pandemic overreaction twenty-four months, a labor deficit of maybe six million or more. That’s potentially a shocking amount of leftover macro slack. |

|

|

Even with the discontinuity in the HH Survey, the 2020 Census data bumping up the participation rate to 62.3% in February, it’s still extremely low (less than the lowest or worst month during the preceding post-GFC1 decade) suggesting, yes, millions in slack. Despite the even lower unemployment rate, we still have that old participation problem to solve on top of this new one. As before, however, the Federal Reserve will be leaning on the unemployment rate and whichever newfangled excuses could help policymakers dismiss participation. Before 2020 it was alleged opioids and presumed laziness, today it’s something the media is trying to call the Great “Resignation”, whatever can make plausible the sense of a tight labor market badly in need of some FOMC rate hike measures. Whether before or after 2020, the data is more likely an acknowledgement that the labor market is not tight at all, and that there still is no such labor shortage. Both the participation rate along with the shocking headline payrolls deficit, thinking this a tight labor market strains creditability – especially since we just did this a few years ago and, as it would turn out, there never was a labor shortage nor tight labor market. |

|

|

|

|

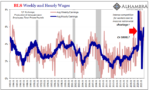

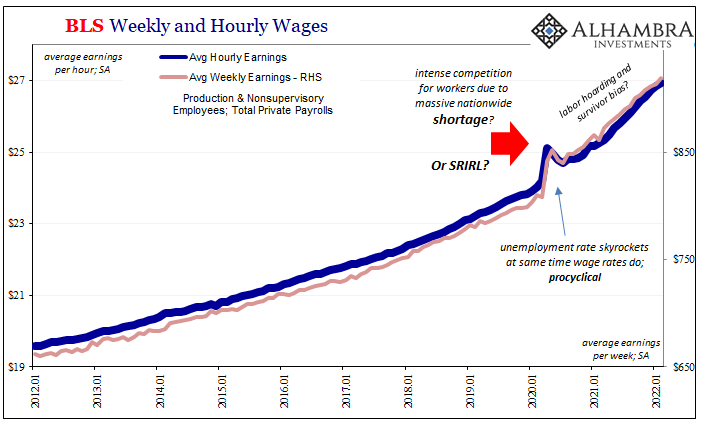

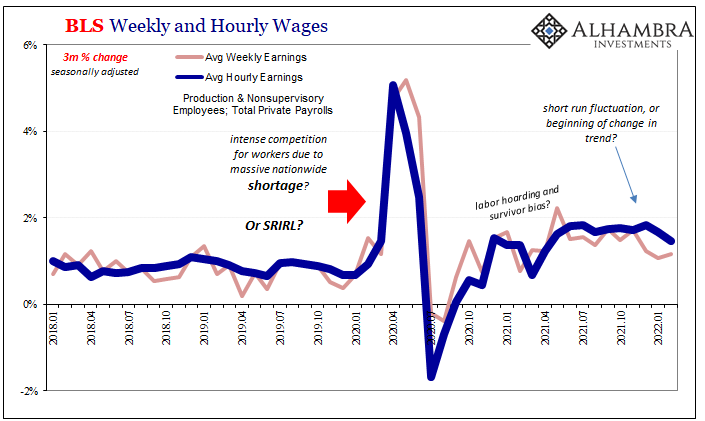

Economists and FOMC members (same thing), however, they have and will continue to point to wages as distinctly different now from then. And that is absolutely true; wage rates have clearly accelerated. But, as I pointed out a few months ago, when they began to accelerate also (strongly) suggests a very different possibility, something called SRIRL.

Had average wages and pay been something other than SRIRL, then we would’ve expected a lot more rejoining the labor force along with new entrants coming into it for the first time – if pay was rising rapidly for reasons other than labor hoarding or survivor biases the participation problem wouldn’t be a problem. |

|

|

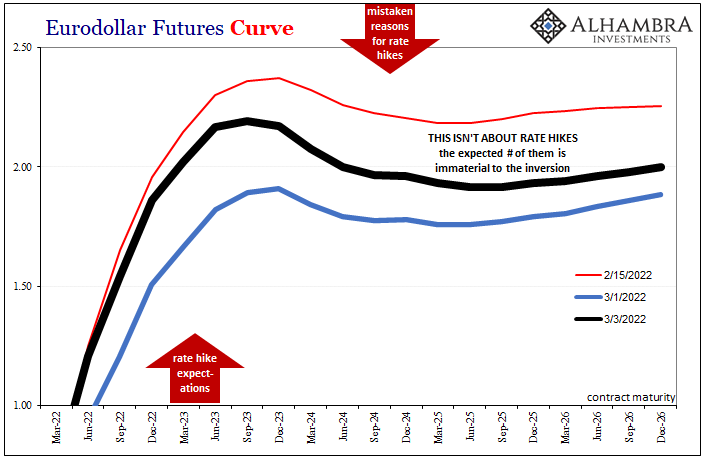

Whatever ultimately the cause, over more recent months the data for both weekly and hourly wages points to a potential slowdown in each – maybe normalizing wages after SRIRL, just usual variations in short-term data, or maybe a change in trend for macro reasons. So far, it is short run so hardly conclusive, and who knows how the BLS might benchmark the hell out of these in the months ahead. Still, this as much as anything might be something to keep an eye on going forward to see how it develops further. Or doesn’t. Not that this will sway the Federal Reserve one way or another; the actions taken by Powell’s FOMC in 2018, they’ve already established that the unemployment rate is good enough. It is their thing. And since monetary policy isn’t about rate hikes at all, rather communicating with the public, what better or easier way to connect with ordinary Americans in the way policymakers believe is fruitful than to link a simple (if wrong) rate with the Fed’s equally simple (if irrelevant) rate hikes. |

|

What is the actual labor market doing all this time? From what we know, it appears to be doing alright; reopening still, though you (and the millions of American workers sitting it out on the sidelines) have to wonder what’s taking so long and what (further) fallout we might expect from this. Maybe the BLS and ADP could’ve taken all this time to figure out how to actually count workers and payrolls.

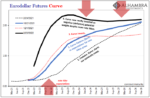

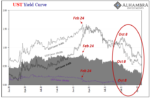

Whether what’s being estimated is enough, and how employment figures tend to be lagging indications, markets are betting more confidently (see: UST 2s10s; eurodollar futures inversion) none of this will matter in the not-too-distant future.

Oil prices and inventories, on the other hand.

As the yield curve drops, is it all pessimism on Russia/Ukraine?

A lot, sure, but not all. Cyclical indications are everywhere, too. pic.twitter.com/ufAwTb85MS

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) March 1, 2022

Tags: benchmark revisions,currencies,economy,employment report,establishment survey,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,FOMC,household survey,jay powell,jobs,labor force,labor force participation rate,Labor Market,Markets,newsletter,payrolls,rate hikes,trend-cycle,unemployment rate,wages