Extraordinary times call for extraordinary commitment. I never set out nor imagined that a quarter century after embarking on what I thought would be a career managing portfolios, researching markets, and picking investments, I’d instead have to spend a good amount of my time in the future taking apart how raw economic data is collected, tabulated, and then disseminated. Yet here we are. I’m not saying, nor have I ever alleged, the government is cheating, cooking the books by overinflating the stats. Rather, the entire economic system deviated back around August 2007 (what I spend most of my time on) rendering past assumptions embedded within data collection processes suspect; to put it kindly Quite simply, the way high frequency data is figured isn’t fully

Topics:

Jeffrey P. Snider considers the following as important: 5.) Alhambra Investments, benchmark revisions, bond market, bonds, currencies, durable goods, economy, exports, Featured, Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy, global trade, imports, industrial production, Inventories, Markets, newsletter, U.S. Treasuries, Yield Curve

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Extraordinary times call for extraordinary commitment. I never set out nor imagined that a quarter century after embarking on what I thought would be a career managing portfolios, researching markets, and picking investments, I’d instead have to spend a good amount of my time in the future taking apart how raw economic data is collected, tabulated, and then disseminated.

Yet here we are.

I’m not saying, nor have I ever alleged, the government is cheating, cooking the books by overinflating the stats. Rather, the entire economic system deviated back around August 2007 (what I spend most of my time on) rendering past assumptions embedded within data collection processes suspect; to put it kindly Quite simply, the way high frequency data is figured isn’t fully suitable for these unusual macro circumstances.

Eurodollar University’s Making Sense; Episode 32; Part 2: Plucking Out By The (Unit) Root

Most of the time, no one notices apart from “unexpected” persistent low-grade growth rates (that are excused and ignored in the financial media’s cheerleading for imagined Federal Reserve successes). Even fewer notice when those eventually disappear entirely in this sanctioned bit of unintentional gaslighting.

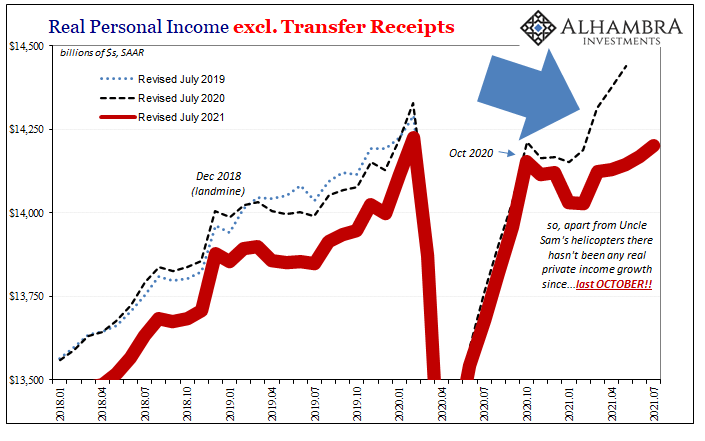

I’m talking (again!) about benchmark revisions and why everyone really should care about them. One day during a particular year, whichever government statisticians (usually Census) say whatever economic data is disappointing at X, then several years later they quietly admit in truth X had been substantially less.

By then, to the public it might all seem moot anyway. It’s not – because this keeps happening, especially around economic turning points.

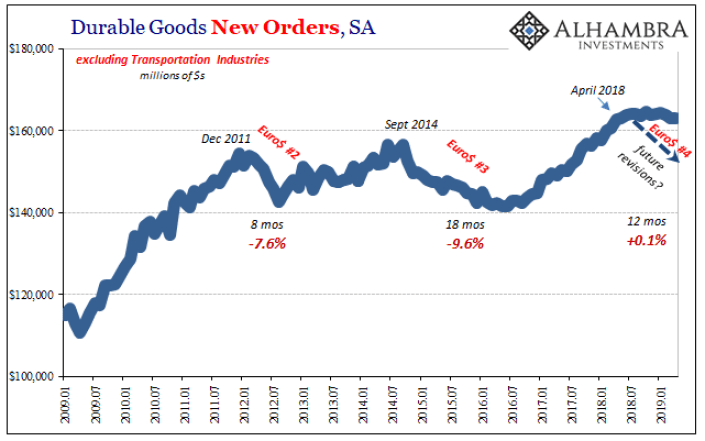

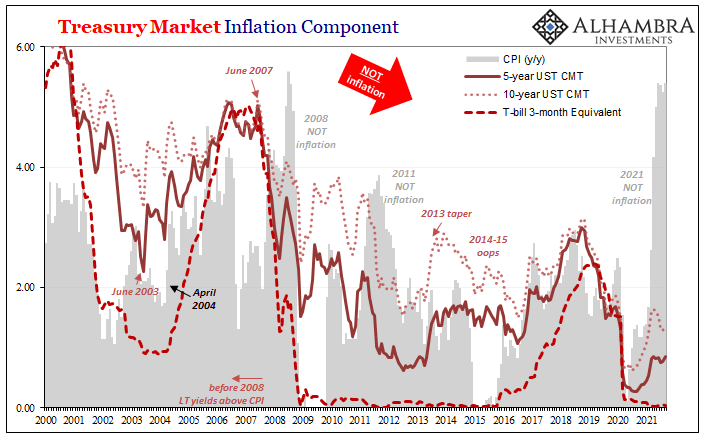

More than two years ago, in May 2019, it was another rash of benchmark revisions this time for durable goods. Only, the focus of revisions for that year’s subject data was exclusively seasonal adjustments rather than the whole underlying series. It was a missed opportunity for the estimates to get corrected in the way the bond market (yields are always on the spot) was trading that whole time.

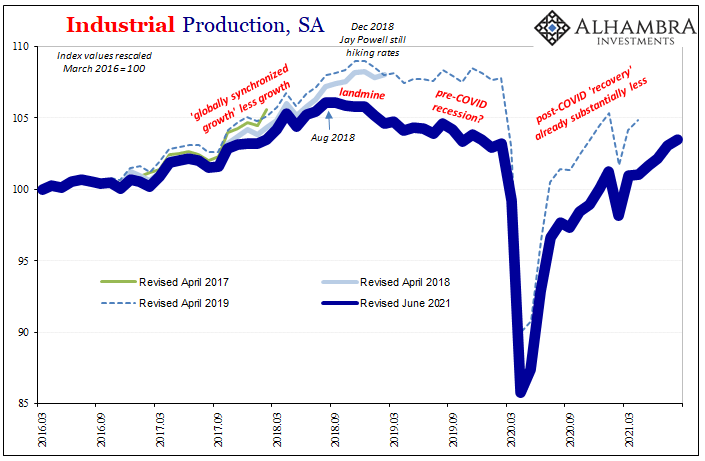

Durable goods new orders (as well as others, like the Federal Reserve’s Industrial Production; it’s not always Census, all statistical series embed the same flaw whose name is trend-cycle) weren’t really declining all that much, perhaps making it appear like the bond market was making too much out of what by May 2019 was being called nothing more than a soft patch (even that was a shocking disappointment given how expectations in 2018 were being directed).

| Was it nothing more than that, as the FOMC began to believe; or, was it really like yields were trading, a more substantial therefore serious downturn maybe even heading right for recession?

I cautioned right then in May 2019, even projected how the situation was almost certainly worse than the data at the time (even after the 2019 benchmarks) put it.

Here’s the chart I produced two and a half years ago; notice the arrow at the far right: |

|

| Durable goods orders, like the Fed’s IP, made it seem as if the goods economy was having a bit of a rough time, sideways lack of growth, but nothing too serious which might warrant more sustained caution and concern. This was at odds with money and yield curves globally which at that very time were being contorted and twisted as if the overall situation wasn’t accurately depicted in these various mainstream series.

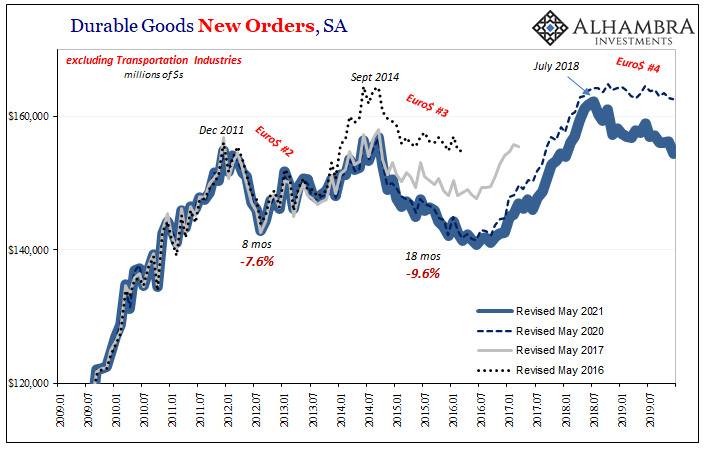

You know where I’m going with this. It did take two years, earlier this year Census (like the Fed) would correct the record. Bonds really were right all along: |

|

If bonds say one thing that may not look the same way in some of these statistics, put your faith (and more) in the continually validated bond view. I said the same thing one year earlier, in 2018, in that case reviewing the 2014 inflection from Reflation #2 into Euro$ #3:

|

|

| There aren’t any mainstream articles written about how durable goods orders just disappeared from the accounts years afterward.

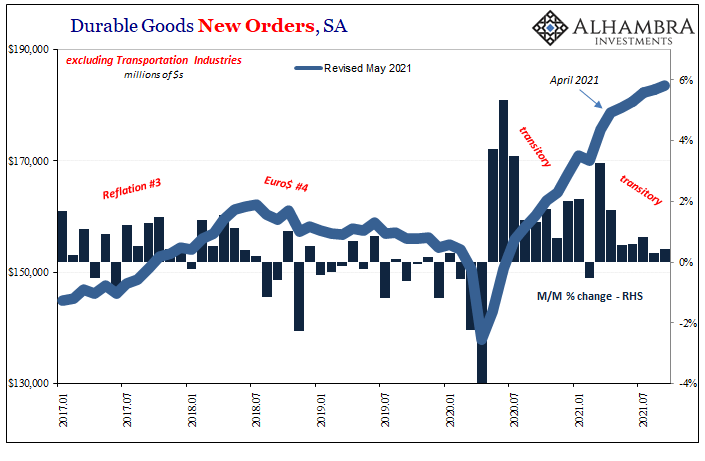

My point is not to pat myself on the back, first of all because I didn’t really do anything more than point out what should have been obvious to everyone. This was, after all, a repeating and strikingly consistent pattern. The techniques statistical data providers use to calculate economic accounts like durable goods have had exhibited uniform trouble underestimating weakness especially around these inflection points; from reflation to the next Euro$ #n and so on. With this tendency toward overestimating in mind, let’s look at some of the recent data beginning with – what else? – this morning’s advance durable goods orders for the month of September 2021: |

|

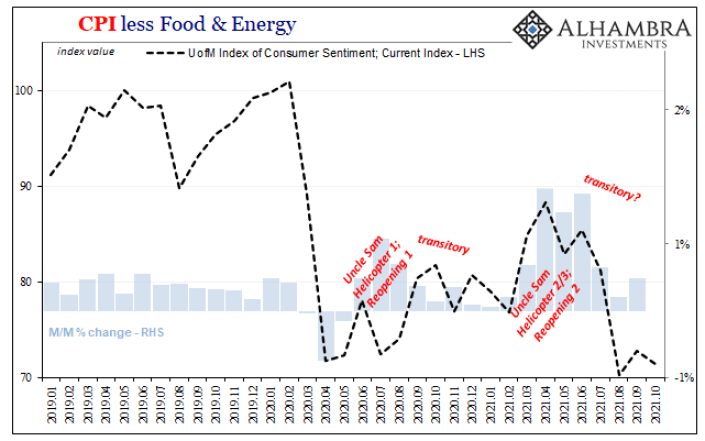

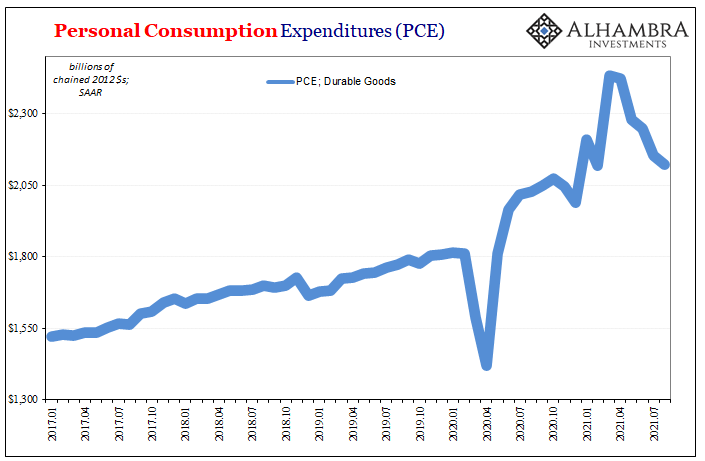

| Orders for product continue to rise, though the rate at which they’ve gained has clearly fallen way off from earlier this year. As everything else around the world, April sticks right out as the possible inflection point.

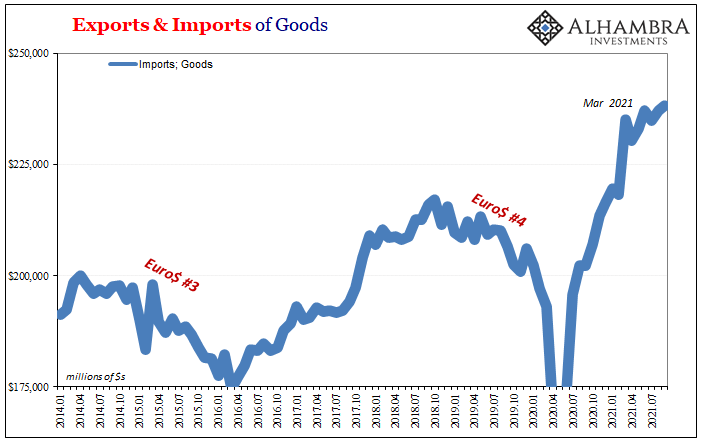

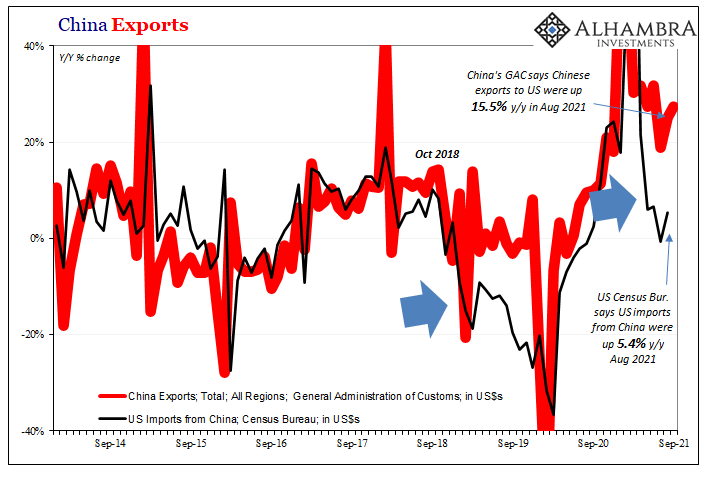

That particular calendar spot of modulation is easily located in a broad cross-section of accounts, both here as well as overseas. The Census Bureau also released today, for example, its advance estimates for exports and imports; the latter germane to our current discussion. More pronounced than the slowing in durable goods, there was no need to add the month-over-month rates to the chart: |

|

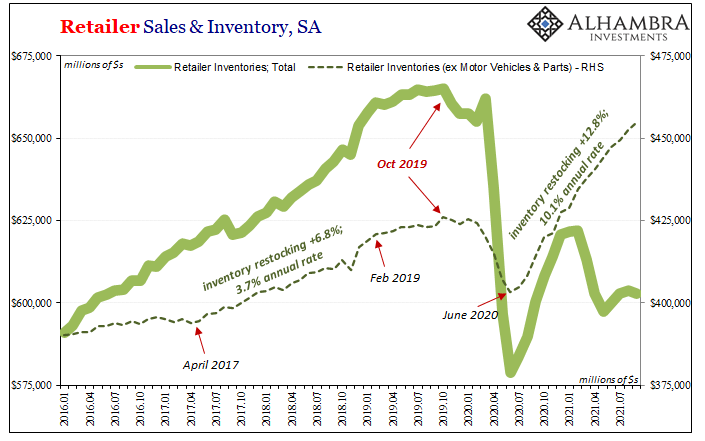

| The Census Bureau also released preliminary assessments for retailer and wholesaler inventories. Since these are early peeks at the inventory data, the government doesn’t give us the full break down by subsections. What has been released is another whopping increase in wholesale inventory (not pictured), a further 1.1% gain in September from August (on top of August’s revised 1.2% increase from July).

This despite what is almost certainly another decline in wholesale inventories of automobiles and parts. We can make this assumption given the release of retailer inventories which do, at least, separate motor vehicles (below). According to these other early numbers, overall retailer inventories dropped by a billion, or 0.2% August to September. However, ex autos retailer inventories increased by almost three billion, or 0.6% month-over-month, about the same rate as August. Unlike durable goods orders or imports, there hasn’t been any noticeable break in trend: |

|

| The goods keep piling up. I pointed out not long ago how when you adjust for these very different sets of supply factors, automobiles compared to practically everything else, what you quickly find is there absolutely are goods getting through the bottlenecks.

A ton of goods are getting through. Too many? We don’t even know what’s still on the way, having already been ordered previously and now stuck in transit on a floating warehouse, someplace in some physical warehouse which is running out of space, maybe even sitting on a train car around Chicago (would this count as wholesale, retail, or some sort of statistical no-man’s-land in between?) The very apparent problem here, the one being traded in bonds since, you know, around April, is that “stimulus” doesn’t actually stimulate. |

|

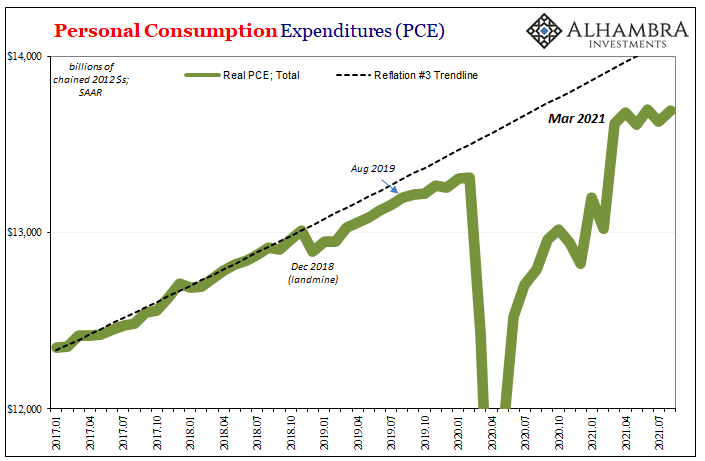

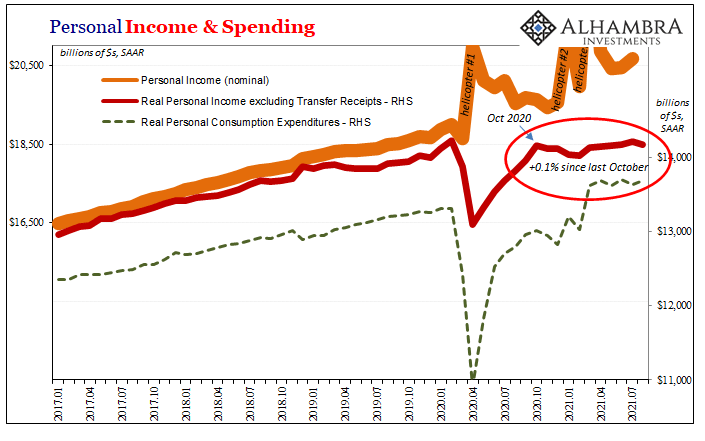

| Sure, there are some short-term impacts, even significant near-term surges, but only Economists and corporate entities who use their forecasting actually believe there’ll be tangible, lasting positive effects.

This 2021 recovery narrative was merely the smoke and mirrors of that transitory burst, including CPI’s, and now the overall global system is realigning back with the 2020 recession economy from which no one had recovered (see: labor market). |

|

| This could very well mean already high levels of inventory companies thought they’d handle without issue, now without the continued demand they were told by their Economists to expect the whole thing would start to roll over. Too much inventory, regardless of logistical issues, possibly triggers(ed) the same inventory cycle that we saw (and predicted even though it wasn’t in the data at the time) in 2018 as well as 2014 and 2012.And this would be, also again, consistent with another round of “impossibly” low and stubborn interest rates further supported by a seriously, quickly flattening yield curve – and all the eurodollar deflationary dimensions that consistently go along with those. | |

|

The mainstream is still convinced 2021 is the year of inflation, so much that even the FOMC has painted itself into its imminently infamous taper corner. We’ve already seen one of the most important datasets (personal income!) revised for this year, would it really surprise anyone if the situation is at least a touch more to the downside risks, even if such a thing isn’t confirmed in the rest of the government’s data for another several years? That’s what bonds are and have been betting. Not just this year, every year. |

Tags: benchmark revisions,bond market,Bonds,currencies,durable goods,economy,exports,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,global trade,imports,industrial production,Inventories,Markets,newsletter,U.S. Treasuries,Yield Curve