We see significant upside risk for global trade coming from “top down” forces (such as politics), but at the same time we expect the undercurrent reconfiguring many of the existing relationships to intensify. The “Peak Globalization” narrative (at least regarding trade) is being challenged by hopes of a revival of multilateral cooperation under Biden and the latest Asian trade agreement. But this doesn’t change our long-term view that the US and China are in an inexorable trajectory of decoupling. The backdrop is highly complex, involving: a leaderless WTO, changing trade patterns in Asia, the new UK-EU relationship, post-Covid supply chain restructuring, Trump’s final salvos against China, and Biden’s incoming administration, amongst others. We will tackle a few

Topics:

Win Thin considers the following as important: 5.) Brown Brothers Harriman, 5) Global Macro, developed markets, emerging markets, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

We see significant upside risk for global trade coming from “top down” forces (such as politics), but at the same time we expect the undercurrent reconfiguring many of the existing relationships to intensify. The “Peak Globalization” narrative (at least regarding trade) is being challenged by hopes of a revival of multilateral cooperation under Biden and the latest Asian trade agreement. But this doesn’t change our long-term view that the US and China are in an inexorable trajectory of decoupling. The backdrop is highly complex, involving: a leaderless WTO, changing trade patterns in Asia, the new UK-EU relationship, post-Covid supply chain restructuring, Trump’s final salvos against China, and Biden’s incoming administration, amongst others. We will tackle a few of these topics in this piece.

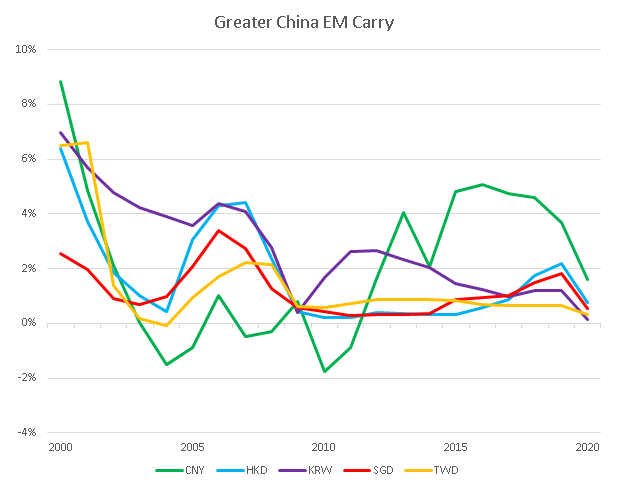

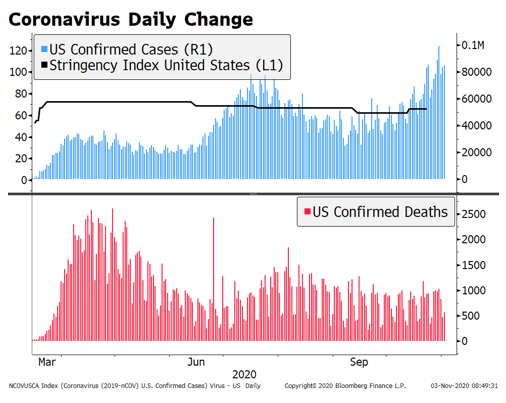

Our investment conclusion is that the net effect of these factors will likely be positive for certain EMs but could increase near-term inflationary risks in the US and China. Although many developments point towards a more multilateral path ahead for global trade, there are a lot of obstacles (see below) for this to be put in practice. There could be a timing mismatch by which the US-China decoupling (inflationary) occurs before multilateral trade developments or effective supply chain realignments (deflationary). For EM, the spoils of the de-coupling won’t be evenly distributed, as seen during Trump. We think there will be two potential groups of winners: (1) countries able to insert themselves in new global supply chains (Mexico, Vietnam, Poland) or those able to participate in China’s tech infrastructure rebuilding away from US components (Korea, Taiwan). (2) Commodity exporters (LatAm) and intermediary product exporters who will benefit from trade dislocations should the US-China trade conflict intensify again. For example, tariffs by China on US agricultural products increases demand for soy in Brazil.

(1) The WTO is leaderless, and its dispute settlement system stalled by lack of judges. The US is withholding its support of the consensus candidate for Director-General (Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala of Nigeria) and supporting its own favored candidate (Ms.Yoo Myung-hee of Korea). The Nigerian candidate was endorsed by the EU and has the backing of Japan and China, along with numerous developing countries in Africa and Latin America. The US backs the Korean candidate in part because she could help pressure China to drop its “developing country” status under WTO rules. In practice this enables China to provide subsidies in agriculture and set higher trade barriers to market entry than more developed economies. For context, two-thirds of WTO members self-identify as “developing countries” including relatively high-income countries as Qatar, Singapore and the UAE. China’s critics argue that this status affords China, the world’s second largest economy, an unfair advantage in the world trading system.

Our take: We don’t see why China would give up its “developing country” status – at least not without extracting a high price. One possibility here is for this issue to feature in the next round of US-China trade talks and become a token of exchange for concessions by the US. That said, we expect Biden’s administration to represent a more congenial approach to international relations and included in this is how the Western countries will pressure China on its trade practices. This means that Biden might be able to garner broader support against China, perhaps using its WTO status as a rallying point.

(2) State subsidies will feature prominently in the post-Covid world. As mentioned above, China’s WTO status affords it “special and differential treatment” under WTO rules advantages relating to subsidies, which will remain a sticking point. But more broadly, how will the WTO and world leaders think of COVID-19 actions? Indeed, the Nigerian WTO candidate said that one of her priorities would be to ensure that COVID-19 – related government stimulus does not distort production and trade (i.e. by acting as a hidden subsidy, etc.). In short, it’s complicated.

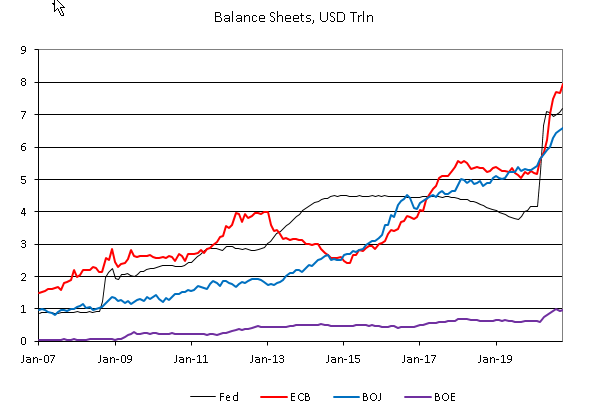

Our take: This could mean an explosion of litigations to trade rules, standing in the way of progress in WTO reforms. The WTO allows for subsidies to be challenged and, given the unprecedented scale of COVID-related stimulus, they could be challenged on an unprecedented scale as well. The problem is that the WTO’s dispute settlement system is stalled because the US has blocked the reappointment of judges to its Appellate body (dating back to the Obama administration).

(3) The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in Asia is an important milestone for global trade, and highly symbolic. While this agreement furthers regional Asian integration (similar to the EU and NAFTA/USMCA), indirect benefits of this agreement are expected to reach as far as the US and EU. A Peterson Institute study estimates that this agreement could add nearly $200bn annually to the global economy by 2030[1]. While not extensive in terms of tariff reduction – and leaving agriculture largely untouched – it eliminates costly rules of origin requirements that had proliferated under the existing agreements.

Our take (US): RECP increases the urgency for the new US administration to return to global stage as a major player in multilateral decision making. Recall that Trump withdrew the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which arguably set the stage for China to adopt a leading role. It’s probably too late to revive the TPP, but we assume the lesson has been learned.

Our take (China): RECP goes against China’s new “dual circulation” strategy since it doesn’t promote a rebalancing towards domestic drivers. The RECP was a decade in the making, so there is a timing mismatch here. But this aside, we think the agreement is coherent with a more nuanced interpretation of China’s new policy: more of a trade rebalancing away from the US than global – and especially regional – trade.

Our take (Asia): The agreement challenges the view that the world is splitting into a bi-polar configuration, along the lines of the Cold War. Practical matter aside, RECP is impressive for being the first agreement to bring together China, Japan and South Korea. This doesn’t mean that these countries have become political allies (nor that the South China Sea dispute will go away). But it shows how (at least for now…) countries are able to align themselves in different ways in terms of trade and geopolitics vis-à-vis US and China interests. India is the notable counter example here, having not signed up for RECP.

(4) Biden will veer towards multilateralism, but simultaneously away from China and raising pressure on Russia and Turkey. The new administration has a chance to reset many of the souring relationships between its trading partners. But also to act upon the Democratic opposition towards the way US-Russian relationship has developed under Trump and (to a lesser extent) Turkey, which could manifest itself as trade sanctions. Growing anti-China sentiment by the US electorate and among politicians across the aisle will ensure continued fuel toward the US-China decoupling trend, and this includes a high risk of sanctions and tariffs. The Trump administration trade sanctions had bipartisan support from a Congress whose makeup will not be widely different following the recent election. Indeed, support from manufacturing states (WI, MI, PA) were key to Biden’s victory, so some version of Trump’s buy-American policy, and some of its trade policy implications, should survive.

Our take: The US President’s Trade Promotion Authority (TPA, or “fast track”) expires in July 2021. TPA renewal may face difficulty passing the House if there were enough opponents in both parties. Moreover, the Senate is still in contention. This could reduce Biden’s degrees of freedom in pursuing a new trade agenda because without TPA, any trade agreements negotiated by the administration are subject to Congressional markups, rather than an up-or-down vote in their negotiated form. Separately, Biden will be appointing a new US Trade Representative in the coming weeks. Different personalities at the negotiating table could allow for progress in unblock the impasse at WTO Appellate Body judges. Indeed, the US recently gained a stay from Chinese retaliation to its tariffs by appealing the decision to the WTO Appellate Body. However, with the WTO Appellate Body is currently paralyzed due to US blockage of new judges, whether this relief will be permanent or temporary is unclear.

[1] Petri, Peter A. and Michael Plummer. Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper 20-9. https://www.piie.com/system/files/documents/wp20-9.pdf

Tags: developed markets,Emerging Markets,Featured,newsletter