It wasn’t entirely unexpected, though when it was announced it was still quite a lot to take in. On September 1, 2005, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) reported that the nation’s personal savings rate had turned negative during the month of July. The press release announcing the number, in trying to explain the result was reduced instead to a tautology, “The negative personal saving reflects personal outlays that exceed disposable personal income.” Why had it become this way? What were the implications, if any? Beyond the scope of the BEA’s mandate, the government could merely recite the progressions behind it: Saving from current income may be near zero or negative when outlays are financed by borrowing (including borrowing financed through credit cards or

Topics:

Jeffrey P. Snider considers the following as important: 5.) Alhambra Investments, commercial credit, Consumer Credit, consumer spending, currencies, economy, Featured, Federal Reserve, Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy, first order effects, jay powell, Markets, Monetary Policy, newsletter, personal savings rate, second order effects, sloos, third order effects

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

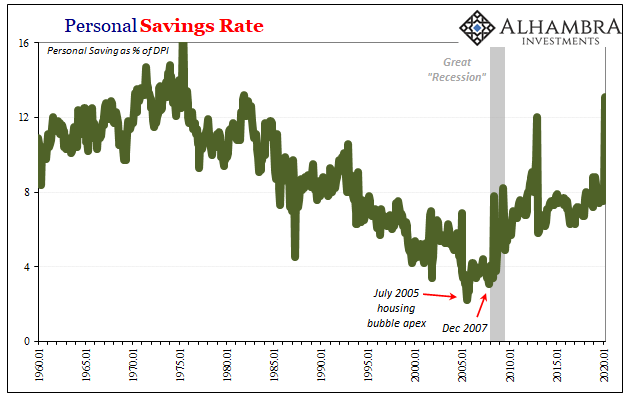

It wasn’t entirely unexpected, though when it was announced it was still quite a lot to take in. On September 1, 2005, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) reported that the nation’s personal savings rate had turned negative during the month of July. The press release announcing the number, in trying to explain the result was reduced instead to a tautology, “The negative personal saving reflects personal outlays that exceed disposable personal income.”

Why had it become this way? What were the implications, if any? Beyond the scope of the BEA’s mandate, the government could merely recite the progressions behind it:

Saving from current income may be near zero or negative when outlays are financed by borrowing (including borrowing financed through credit cards or home equity loans), by selling investments or other assets, or by using savings from previous periods.

The implications, therefore, behavioral.

|

Over the years and the many benchmark revisions in between, the BEA now thinks the lowest the savings rate ever got was +2.2% in that same month of July 2005. Though nominally on the plus side, still an incredibly low proportion. Savings had been falling for decades by then, which is why it wasn’t a surprise at how low the rate would get to be by the middle 2000’s. And it wasn’t just the housing bubble’s apex, that merely drove the trend to its final extremes. Americans had not only come to use debt to such levels, they had come to see it as a dependable expansion of their personal situation. No one would ever need savings, not in the era of the “maestro” and the economy of the Great “Moderation.” Though there had been some rumblings about some giant sucking sound and Democrats complaining (correctly) about George Bush’s “jobless recovery” from the unusually mild dot-com recession, robust global eurodollar business put credit in reach of everyone regardless, it seemed, of any potentially negative factors. The more the better, no risks visible on anyone’s timeline (certainly not Dr. Bernanke’s). That all abruptly changed in December of 2007. Suddenly, the credit suppliers had become shy and grown distant. Debt no longer so much the dependable supply of emergency let alone regular funds. True as much for small companies and big corporations (such as McDonalds and Caterpillar who were reduced to seeking out FRBNY in order to beg the central bank branch to buy each’s commercial paper) alike, as well as consumers. |

Personal Savings Rate, 1960-2020 |

| It represented only the start of a paradigm shift in behavior, one that wasn’t unfamiliar, either. How many stories from our parents and grandparents (or maybe great grandparents, for those of you possibly much younger) who had splurged during the Roaring Twenties only to regret it in the early thirties while being transformed into the most frugal of spenders for the rest of their lives?

Something Economists call a second order effect (or third order, depending on in which order you place these factors). The first order effect was the shock of the Great “Recession”, really the first eurodollar shortage (GFC1). Millions lost their jobs and their access to credit at the same time.This then caused a behavioral change that, as you can see above, was no one-off, temporary rebuke. Demand destruction. The Federal Reserve’s job, as it sees things, is to minimize the first order effect so as to neutralize any second and thirds before what you see above happens. This is not a debate or argument as to what “should” take place; whether or not the savings rate was “too low” during 2005. From the official perspective, it’s about confronting an exogenous shock and making sure its effects don’t change the whole trajectory of the economy (potential). That once the system absorbs that shock, when it’s all over everything can and does go right back to normal (defined as what was going on before the shock arrived) as quickly as possible. |

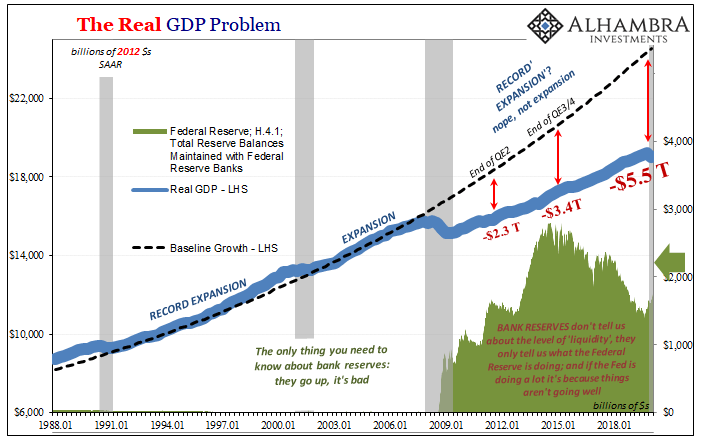

The Real GDP Problem, 1988-2018 |

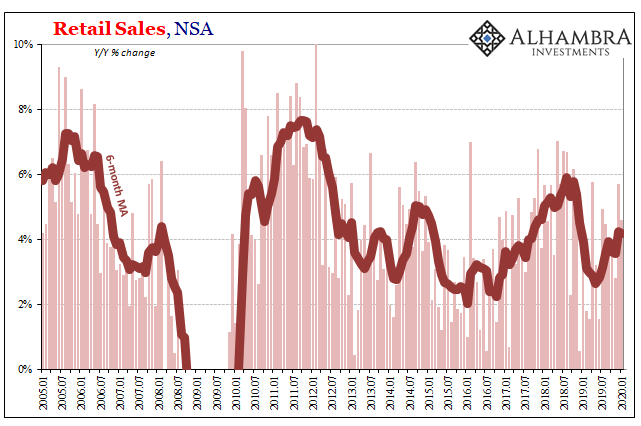

| Second (and third) order effects complicate that effort, and can end up thwarting it entirely (see: below). The lack of credit growth (yes, lack) post-2008 related to mostly asymmetric liquidity risks (no matter the level of bank reserves) has left very deep scars on the global economy. Thus, shock ($ shortage leading to Great “Recession”), second order effect (cut off of credit flow) and then the more direct third (grossly higher savings rate, meaning less spending).

And these then create positive feedback loops; lower aggregate spending because of higher saving (and liquidity preferences) mean lower revenues for businesses who don’t hire back the same number of workers confirming frugality and the same negative effects. If the US central bank had been anything like a dollar central bank rather than a US domestic banking authority, perhaps the liquidity shock in the first order could’ve been more appropriately handled and maybe even circumvented (and that’s debatable, though beyond our scope here). These faults should have been studied carefully, but instead they’ve been discarded or ignored so as to otherwise reverse engineer (R*) failure into a great success for QE and “emergency” monetary policies (colloquially “money printing”). |

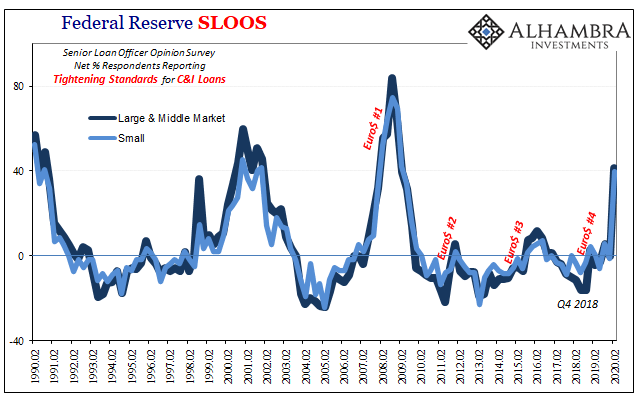

Federal Reserve SLOOS, 1990-2020 |

| And it is upon those same polices, exactly the same, that we are all supposed to expect a very different outcome this time around.

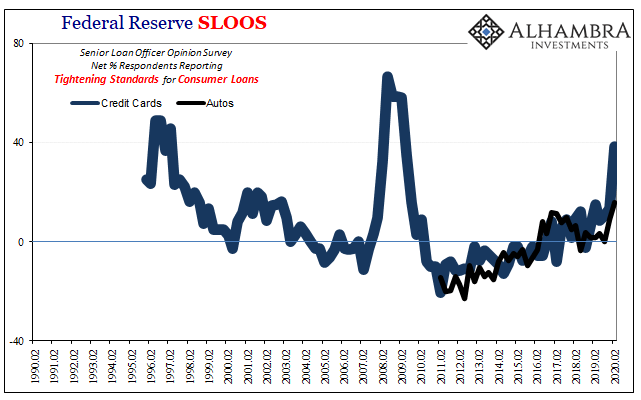

The exogenous shock has already happened, as has the dollar shortage (GFC2). We arrived in May 2020 already deep in the hole. And yet, the idea of an immediate “V” shaped recovery has taken ahold of the collective imagination even though we’ve yet to see any second or third order effects. Tens of millions have been laid off in a very short period, thousands, tens of thousands of businesses closed, but so long as they go right back to work, these people say, then all is economically forgiven and financially forgotten. Is it really that simple? Fat chance. We realistically have to expect some of these later feedbacks, starting with credit availability. And, unsurprisingly, they are already showing up in early April. Every quarter the Federal Reserve surveys the opinions of senior bank loan officers (SLOOS, or Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey) to gauge bank perceptions on all lines of debt issues. From commercial loans and CRE (commercial real estate) to mortgages and consumer credit. |

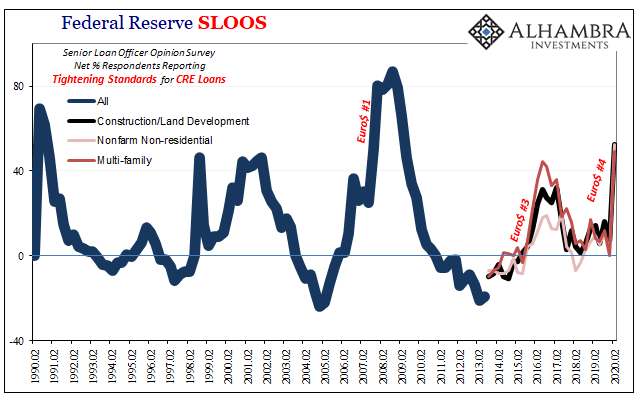

Federal Reserve SLOOS, 1990-2020 |

| The Fed has both a regulatory interest in the results as well as a monetary policy interest insofar as it relates to the effectiveness of monetary policy (expectations) in keeping disruptions to that theoretical safe minimum (no second and third). Is the Fed’s playing around with fed funds or increasing the balances of its alphabet soup programs soothing rattled institutional nerves?

The survey for the second quarter of 2020 was conducted in early April. So, yeah: |

Federal Reserve SLOOS, 1990-2020 |

|

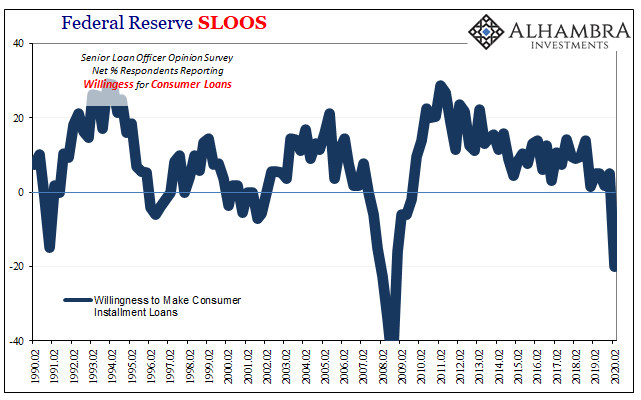

A large increase in the number of respondents reported how their bank has tightened lending standards for all loan products. Thus, while tens of millions are losing paychecks, even if all of them go back to work they will find it harder to qualify for credit on the other side of the shock. Same with businesses; many who are losing profits and might be able to survive in between will also be left without the same level of, and access to, debt. It is looking like an especially large hurdle for consumers. Not only do the SLOOS data point to higher lending standards, it also shows a big change in potential commitment. To put it simply, not many even want to think about installment credit of any kind right now. |

Federal Reserve SLOOS, 1990-2020 |

|

It is these kinds of results that help explain Jay Powell’s seeming aggressiveness. He holds, according to his own ideology, an enormous task ahead of the Fed. It’s not really monetary in nature (though it really should be, that’s the place to effectively start only, again, Powell hasn’t a central bank at his disposal). Their primary job, as officials see it, is for monetary policy to convince the entire economy that all risks are and will remain low. That Powell and his magic is capable of completely papering over the whole world, and the enormously deep hole GFC2 and COVID-19 have just blown in it. Just don’t ask any question about the specifics. |

|

They really believe that if you believe then everything will just go back to normal. No second order effects let alone any third and the self-reinforcing spiral. Unfortunately, over here in reality neither the economy nor the financial system works on fairy dust. Thus, GFC1 and its disgusting, stubbornly awful aftermath.

Maybe banks will change their minds over the months ahead. As of early April, with the Fed on full blast already, they don’t appear to have been all that convinced. Second order effects, right now, are increasingly the order.

Tags: commercial credit,Consumer Credit,consumer spending,currencies,economy,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,federal-reserve,first order effects,jay powell,Markets,Monetary Policy,newsletter,personal savings rate,second order effects,sloos,third order effects