Smug Central Planners Looking back at the past decade, it would be easy to conclude that central planners have good reason to be smug. After all, the Earth is still turning. The “GFC” did not sink us, instead we were promptly gifted the biggest bubble of all time – in everything, to boot. We like to refer to it as the GBEB (“Great Bernanke Echo Bubble”) in order to make sure its chief architect is not forgotten. Naturally, we were premature in calling for the pompes funèbres and the grave diggers in order to inter the GBEB in late March, but the revival in US markets was a muted one and the funeral rites certainly continued in numerous emerging markets. Image credit: Sharon Hatley China is widely considered an

Topics:

Pater Tenebrarum considers the following as important: 6) Gold and Austrian Economics, 6b) Austrian Economics, 7) Markets, Chart Update, Featured, newsletter, On Economy, On Politics

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Smug Central PlannersLooking back at the past decade, it would be easy to conclude that central planners have good reason to be smug. After all, the Earth is still turning. The “GFC” did not sink us, instead we were promptly gifted the biggest bubble of all time – in everything, to boot. We like to refer to it as the GBEB (“Great Bernanke Echo Bubble”) in order to make sure its chief architect is not forgotten. |

|

| China is widely considered an important element in assorted bubble revival operations these days and the vast credit expansion ordered by the Politburo after the GFC bears testimony to this. The seeming success of these interventions does breed smugness – consider an excerpt from a panel at the last Davos pow-wow shown below, in which Fang Xinghai, Vice-Chairman of the China Securities Regulatory Commission, hails the ability of the government to intervene forcefully and quickly as the be-all and end-all needed to keep things on an even keel.

To be sure, he does admit right away that there are “costs” associated with this, without going into too much detail about them. He also points out to his fellow panelists that when your stock market is more overvalued than at the peak in 1929 (showing them a chart virtually all of Wall Street has tried to studiously ignore for the past three or four years), you have no business worrying about bubbles elsewhere. Perhaps you should be more concerned about your own. Let us take a brief look. This is a lengthy video, and the part we are referring to begins at 48:52. Here is a direct link with the start time embedded, alternatively you can look at the version of the video embedded below, by navigating to the 48:52 time stamp on your own. |

Fang Xinghai opines on the US stock market bubble and the supposed invincibility of China’s financial system |

| We will give Fang this: people trying to bet on a “financial collapse” in China haven’t had much success so far (if one disregards recent weakness in the yuan). It is true that the government can very quickly and decisively intervene by ordering credit expansion ex nihilo and misdirecting scarce resources into more and more capital malinvestment.

What Fang didn’t mention: in the process an ever larger debt pile is built up, even while the ability to service this debt is weakened concurrently, as more and more loss-making zombie undertakings are kept afloat alongside a shrinking number of viable investments. We also believe that people tend to underestimate the strong entrepreneurial spirit of the Chinese citizenry; moreover, it may well be that aggregate statistics are not truly doing the size and power of China’s economy justice. There are undoubtedly many great things happening in China, where hundreds of millions of people have achieved a decent living standard after being mired in poverty for decades. These favorable factors provide an overarching backdrop for a positive long-term outlook, but they are probably not really relevant to the situation currently at hand. |

USD-CNY weekly over the past five years. |

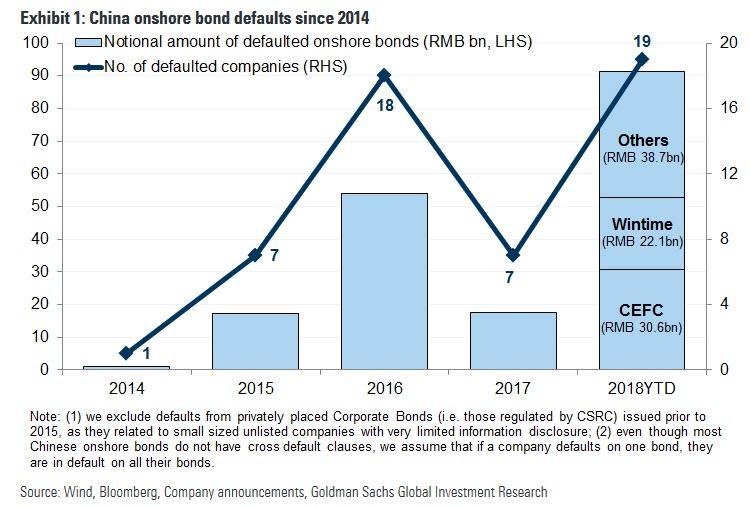

Crunch Time in China?With another major centenary approaching – namely the centenary of the founding of China’s Communist Party in 2021 – it was apparently decided to act counter-cyclically by tapping on the monetary brakes just in time. The chart below was recently shown in a Zerohedge article about well-known China bear Kyle Bass. It illustrates that slowing money supply and credit growth in China are slowly but surely having an impact on more and more economically weak undertakings, as corporate bond defaults continue to surge: |

China onshore bond defaults since 2014 |

| It appears that the plan is to prime the pump again just in time for the above-mentioned centenary, so as to make sure the right economic backdrop prevails in 2021: no bust conditions, no financial crisis, etc. It is surely no big stretch to believe that the Politburo would prefer to see a boom at the time. And so the bitter pills are swallowed now, or so the thinking seemingly goes.

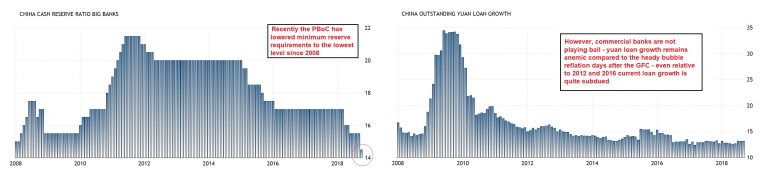

We admit we have no idea how many more times this rabbit can be successfully pulled out of China’s hat, so to speak. After all, we cannot measure the state of the country’s pool of real funding, but this accumulated pool of real capital is what makes seemingly successful interventions even possible. It therefore also represents the limit to what can be done (“political will” alone is not enough). For the near term outlook one must consider various monetary data in China. Recently the PBoC has eased monetary conditions by lowering minimum reserve requirements (MRR) again, but this is partly a function of the ongoing, slow drain in China’s foreign exchange reserves (the PBoC uses MRR to partially “sterilize” foreign exchange inflows). Interestingly, despite the decline in forex assets, the central bank’s balance sheet continues to grow. |

China forex reserves and PBoC balance sheet |

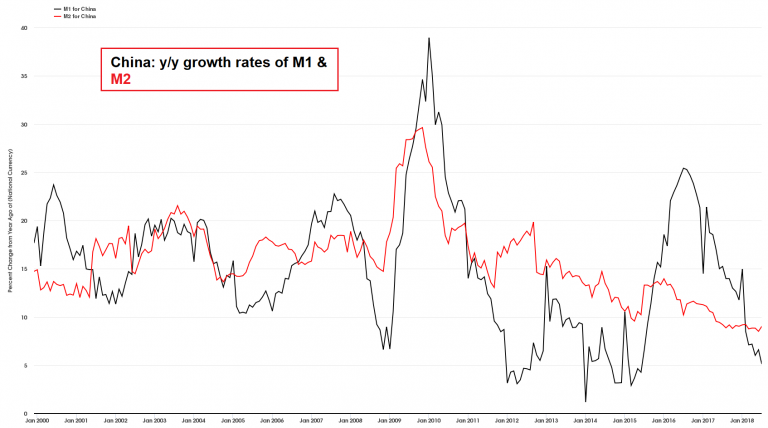

| In short, the PBoC is certainly not overly “tight”, but it is also not as accommodative as it would have to be to egg on credit and money supply growth in China forcefully. This is evidenced by the year-on-year growth rates of China’s monetary aggregates M1 and M2:

It seems China’s commercial banks are unable or unwilling to come along and ease their own lending standards to an appreciable extent. This could be a sign that bankers are becoming concerned about the pool of real funding and the ability of borrowers to repay their debts. |

China, y/y growth in the monetary aggregates M1 and M2The latter is near its lowest growth rate since at least 2000 (when this data series begins), while the former is also at an uncommonly low 5%. If one looks carefully, by the time the market scares occurred in 2015 and early 2016, M1 was already expanding sharply again – in other words, it was the lagged effect of the previous slowdown in monetary growth rates that began to impact financial markets. This suggests that the impact of the current slowdown has not played out in full yet. |

| Of course, everything suggests that all it would take to make them change course is a nudge and wink from above, but there are always those pesky “costs” – and if the concerns of China’s commercial bankers are legitimate (we would suggest they are), then such a decision could easily lead to disaster right away. Currently the PBoC’s comparatively easy stance with respect to MRRs certainly seems at odds with the pace of yuan loan growth in China: |

China MRR and loan growth |

| China’s stock market has only experienced a mini echo bubble after the GFC, which mostly took place between 2014 and 2015. Then oil prices started to decline and the emerging market slowdown began to bite – all of which appeared primarily related to the fact that both China and the Fed were pulling back from extreme monetary accommodation at the same time (ECB accommodation had yet to fully kick in).

After a brief – albeit weak – recovery phase, China’s stock market has entered a kind of “grinding bear market” that has in the meantime undercut the lows of the sharp 2015 – 2016 decline. Nevertheless, so far the effects of a relatively tight monetary environment in China and the US are actually more strongly felt in other emerging markets, many of which inter alia depend on strong commodity prices. A few EM stock markets even look downright cheap by now and even Chinese stocks look superficially inexpensive. Alas, as noted above, the effects of the credit crunch are highly unlikely to have played out in full just yet. Patience seems definitely advisable at this juncture, especially as developed market stock markets currently look as though they want to fall out of bed with a big thud in order to play catch-up. |

$SSEC weekly from 2014 to today |

Conclusion

The accelerating liquidity drain orchestrated by the Fed is beginning to weigh noticeably on “risk assets”. From 2015 to 2018, there was a degree of offsetting monetary accommodation from the ECB and BoJ, and this year Mr. Trump’s tax cuts and deficit spending have provided a dose of “stimulus” as well (even if spending merely shifts resources around and cannot create viable new ones). Arguably all of this has helped extend the cycle well past its due date.

This is just a reminder that China is yet another major force currently contributing to monetary tightness rather than looseness. How things will play out this time around remains to be seen, but once again it will probably pay for investors to remain very cautious and adopt a wait and see stance.

Charts by: BigCharts, TradingEconomics.com, StockCharts, Zerohedge / Goldman Sachs, St. Louis Fed

Tags: Chart Update,Featured,newsletter,On Economy,On Politics