The eminent Oxford historian says that there is nothing new about globalisation, which began as much as 3,000 years ago. A key moment was when Alexander the Great’s conquests connected three continents and opened trading routes between the great cities of antiquity. What was the role of Alexander the Great in globalisation? His conquests between 334 and 323BC drew together North Africa, Europe and Asia and created what could fairly be called a global exchange system. Coins minted by his successors in the East bore Greek text and Indic script, and when Ashoka, the great early Indian emperor started issuing his Edicts a century later, he used multiple languages across the centre of Asia – including Greek, as well as Sanskrit and Indic.Images of the Trojan War and of Hercules standing next

Topics:

Perspectives Pictet considers the following as important: Evolution of cities, In Conversation With, Pictet Report, Pictet Report Winter 2018

This could be interesting, too:

Perspectives Pictet writes House View, October 2020

Perspectives Pictet writes Weekly View – Reality check

Perspectives Pictet writes Exceptional Swiss hospitality and haute cuisine

Jessica Martin writes On the ground in over 80 countries – neutral, impartial and independent

The eminent Oxford historian says that there is nothing new about globalisation, which began as much as 3,000 years ago. A key moment was when Alexander the Great’s conquests connected three continents and opened trading routes between the great cities of antiquity.

What was the role of Alexander the Great in globalisation?

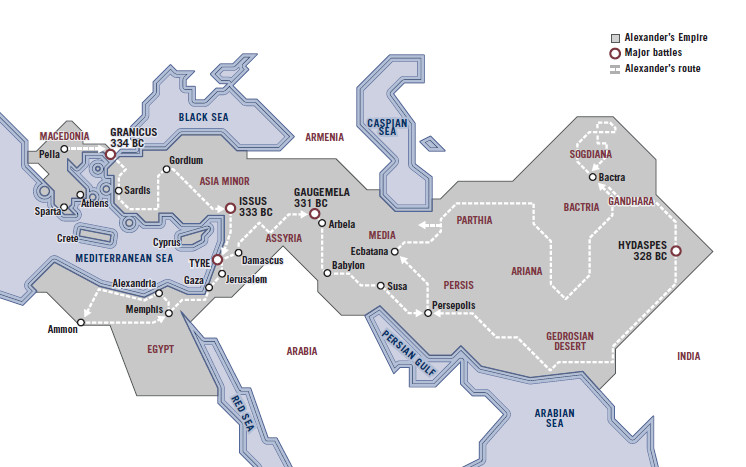

His conquests between 334 and 323BC drew together North Africa, Europe and Asia and created what could fairly be called a global exchange system. Coins minted by his successors in the East bore Greek text and Indic script, and when Ashoka, the great early Indian emperor started issuing his Edicts a century later, he used multiple languages across the centre of Asia – including Greek, as well as Sanskrit and Indic.

Images of the Trojan War and of Hercules standing next to the Buddha can be seen at Gandhara in the Indus Valley, while sculptures of the Titan Atlas, who carried the Earth on his shoulders, can be seen in Afghan temples. Around the same time, China under the Han dynasty began to cast its horizons westwards – to the heart of Asia. That led to the birth of the networks that have been known as the Silk Roads since the late 19th century.

All these peoples wanted to understand how the world was connected, where the best products were made and how people defined themselves by what they wore – just as we do today. And it is interesting that when Alexander set out to conquer the world, he had no interest in Western Europe. What mattered were North Africa, the Middle East and Asia, where the world’s great civilisations originated; the first cities were built; the first laws passed and early scholars were based. The East was where history was made at that time, in Persia and at the first battle of Troy – never in Spain, France or England.

The Empire of Alexander the Great

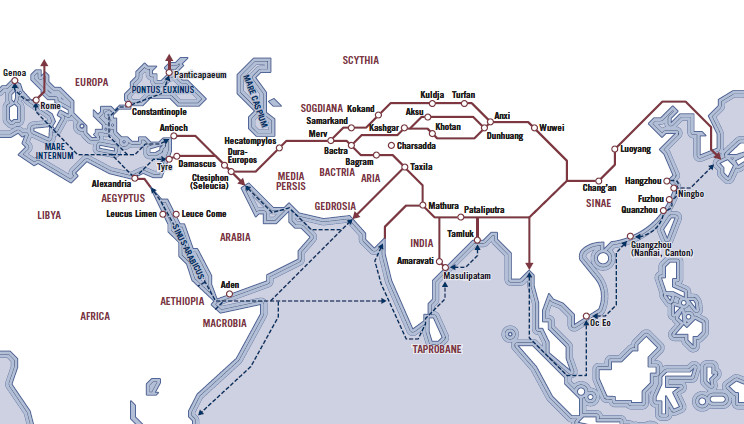

Eurasian trade routes in the first century AD

Your latest book about the Silk Roads has been very successful – and a best-seller in China. What role did they play in shaping the modern world?

The Silk Roads describe trade routes that developed to link Asia with Africa and Europe by land and also by sea. They brought camel trains laden with goods across the deserts and mountains of Central Asia, through large trading cities, which played a fundamental role in shaping the modern world. One was Merv in modern-day Turkmenistan, which was the world’s largest city for centuries – in 1200 its population numbered a million at a time when London had just 20,000 inhabitants. Others included Samarkand in modern-day Uzbekistan, one of the oldest inhabited cities in Central Asia, and Ctesiphon in modern Iraq, capital of Parthia and another of the world’s largest cities.

The Silk Roads were used to trade with the Roman Empire 2,000 years ago, running all the way from the Pacific coast of China to the eastern Mediterranean and the Red Sea. The map overleaf is based on texts commissioned by the Emperor Augustus to explain what was where, what could be bought and what could be sold, as well as on parallel works produced in China around the same time to record the same things. Villas in the Mediterranean used wood from Vietnam and South-East Asia, and there were pots made in North Africa, which have been found in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides.

Pots almost certainly made in Basra have been found in shipwrecks off Sri Lanka, which probably sank on their way to China. For their part, the Chinese were interested in what the Romans had in military and other technologies. And there were coinages designed to look and feel the same – single currencies allowing transactions to take place.

Exchange along the Silk Roads was not limited to trade of goods. Ideas were also brought from place to place by merchants, travellers, soldiers and holy men. Not surprisingly, amongst the most important were ideas about the divine. So faith and religion played important roles in the connections made by the Silk Roads.

Yet surely the Roman Empire was quintessentially European?

The richest part of the lands around the Mediterranean was in North Africa, where the provinces of Egypt and what is now Libya provided the grain that fed Rome’s population. But Rome’s main focus looked eastwards towards the Parthians, the Persians and other peoples.

Eventually it dawned on the Romans that their capital city was in the wrong place, and a new city was built by Emperor Constantine in 330 AD. Constantinople was at the meeting point of Europe and Asia, dragging the whole empire towards the East. After Rome was sacked by the Huns, Goths and Vandals in 410, Constantinople carried on functioning in the East for more than a thousand years as the capital city of the Eastern Roman (or Byzantine) empire.

The heart of Asia was where all the action took place and where all Europe’s religions came from and competed with each other – like Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism and Islam. We think of Christianity as European, but Jesus spoke in Aramaic and the new faith originated from Jewish prophecies made in the Middle East. Islam arose in Arabia, but spread to places like Damascus, Mosul and Baghdad – and far beyond through North Africa to Spain. Buddhism was brought along the Silk Roads by travellers who wanted to exchange ideas. Religious images are similar in many religions, with halos around holy heads and angels seen on either side of the Buddha.

It was also where all the world’s major languages arose: Semitic, Caucasian, Indo-European, Sino-Tibetan and the Altaic languages of the steppes. Europeans arrived in successive waves of migration from the East and spoke Indo-European languages

But what about modern values and human rights – are they not European in origin?

The greatest empire of late antiquity was created after the death of Mohammed in 632, and it linked the richest parts of the Roman Empire with the entire Persian empire. It drove trade and, like all trading empires, was tolerant – money and trade make people respect each other’s differences. As in the modern world, things were not always smooth and happy. But it is very hard to trade with people who are not like you if you want to persecute or kill them – or treat them as inferiors.

It was an era of artists, craftsmen and scholars, whose learning preserved aspects of Greek civilisation that were under attack, often by Christians in Europe. The Islamic world learnt to understand globalisation, business and entrepreneurship and to develop early human rights.

The trade routes across Asia also brought dangers. The Black Death followed the invasions by the Mongols, who also deployed violence on their advances. Two great Asian cities on the Silk Roads – Merv and Nishapur – were completely destroyed when they resisted them. Not surprisingly, this persuaded other cities to negotiate with the Mongols, who were astute in conceding religious tolerance and promising less tax if they opened their gates.

So when does Europe come into the picture?

Europe until 1500 was a backwater, with a few impressive castles that reflected how European societies were built on inequality. The whole point of the feudal system was to have barons at the top whose families tried to protect their wealth over generations.

In contrast, Asian invaders created successful societies in multi-ethnic, multi-religious and diverse regions over long periods by promoting on merit. The Byzantines, Huns, Mongols and Ottomans were ruthless at constantly redistributing assets towards people who could work them harder, preventing the emergence of aristocracies.

However, Europe began to change after the Black Death killed around 35 per cent of its population. Those who survived lived for the day rather than saving for an uncertain future, sparking a financial boom that reduced social inequality and galvanised Europeans into exploring the world. Columbus and Vasco da Gama voyaged to the Americas and India, putting Europe at the centre of global trade networks for the first time by adding the Americas to the three continents where trade had been concentrated for thousands of years.

Large amounts of mineral wealth flowed back across the Atlantic, providing the resources that allowed the Renaissance to happen. It wasn’t just that Europeans became clever: they became rich, and the rich paid for the arts and architecture behind the enormous expansion of cities such as London and Amsterdam. Europe became a powerful force in the world by entering global trade networks, and it was quite successful in remaining at their centre for the following 400 years.

What comes next?

All great global cities have risen and fallen through history, from Athens and Rome to Venice. Those that prospered in the age of Europe’s empires have gradually declined as the great trading cities of older empires have revived by joining the global market system. In the 21st century, new life is being breathed into the arteries and veins that link the East and West, the modern equivalents of the Silk Roads.

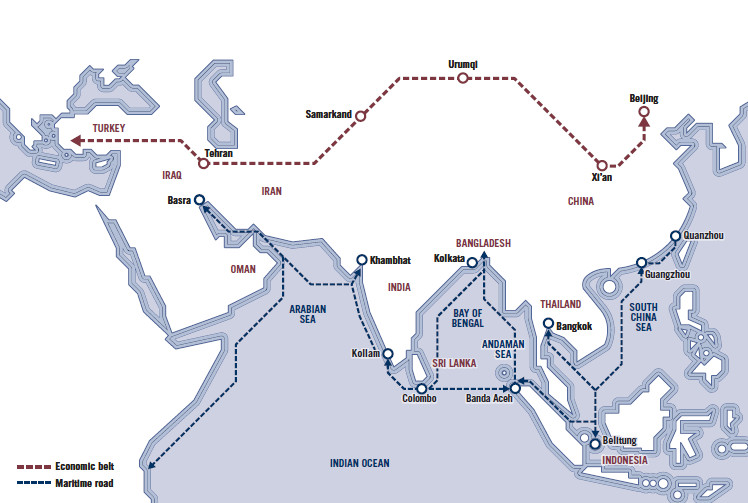

One of the most interesting developments has been the launch in 2013 of China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative by President Xi Jinping. This involves major investment in train lines and roads from China to Europe through the trading centres of the Silk Roads, and through deep-water ports in its maritime equivalent across the Indian Ocean. It covers where 70 per cent of the world’s population live, and will lead to a further period of radical change.

Playing a key role in future developments will be the world’s megacities, especially in Asia, where urbanisation is happening on a scale unprecedented in human history. In China, 60 per cent of people will have become urbanised over 30 years – a process that took 250 years in Europe.

An old Confucian saying says that if you do not understand the past, it is impossible to understand the future – but also to understand the present. Asia is where the fate of the world – and its shape – will again be decided.

One Belt, One Road

Peter Frankopan

Peter Frankopan is Professor of Global History at Oxford University, where he is also Senior Research Fellow at Worcester College and Director of the Oxford Centre for Byzantine Research. He works on the history of the Medi-terranean, Russia, the Middle East, Persia, Central Asia and beyond, and on relations between Christianity and Islam. He also specialises in medieval Greek literature. His book The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, is an international bestseller in countries including the UK, US, Germany, China, India, Pakistan and the UAE.