THE GLOBAL financial crisis of 2007-09 was socially divisive as well as economically destructive. It inspired a resentful backlash, exemplified by America’s Tea Party. That crisis at least had the tact to spread financial pain across the rich as well as the poor, however. The share of global wealth held by the top “one percent” actually fell in 2008. The pandemic has been different. Amid all the misery and mortality, the number of millionaires rose last year by 5.2m to over 56m, according to the Global Wealth Report published by Credit Suisse, a bank. The one percent increased their share of wealth to 45%, a percentage point higher than in 2019. The wealthy largely have central banks to thank for their good fortune last year. By slashing interest rates and

Topics:

Finance & economics considers the following as important: 3.) Economist on Swiss banks, 3) Swiss Markets and News, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

| THE GLOBAL financial crisis of 2007-09 was socially divisive as well as economically destructive. It inspired a resentful backlash, exemplified by America’s Tea Party. That crisis at least had the tact to spread financial pain across the rich as well as the poor, however. The share of global wealth held by the top “one percent” actually fell in 2008. The pandemic has been different. Amid all the misery and mortality, the number of millionaires rose last year by 5.2m to over 56m, according to the Global Wealth Report published by Credit Suisse, a bank. The one percent increased their share of wealth to 45%, a percentage point higher than in 2019.

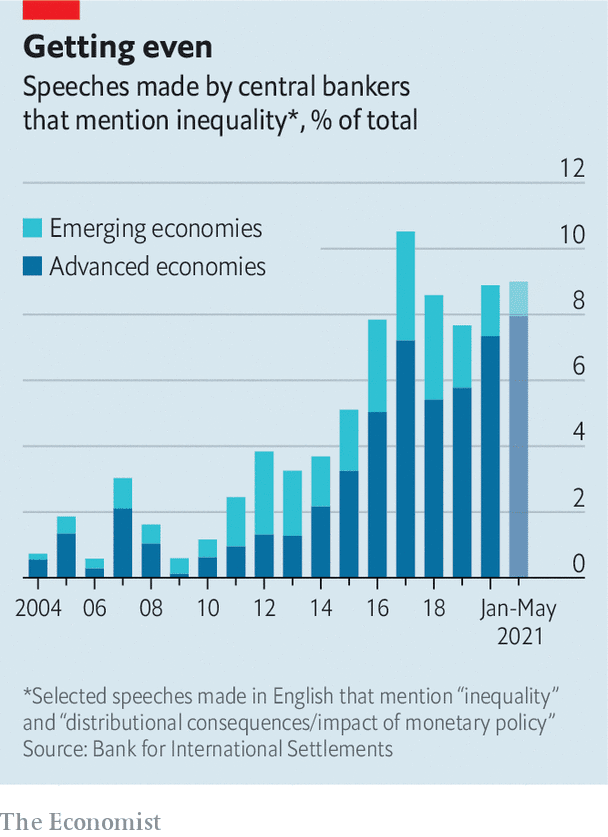

The wealthy largely have central banks to thank for their good fortune last year. By slashing interest rates and amassing assets, central banks helped the price of shares, property and bonds rebound. Their economic-rescue effort was, in many ways, a triumph. Yet central banks are not entirely at ease with the role they have played in comforting the comfortable. In October Mary Daly of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco contrasted America’s full financial rebound with its incomplete economic recovery. “It seems unfair,” she acknowledged. “Another example of Wall Street winning and Main Street losing.” Her speech fits a trend; central bankers are mentioning inequality more often (see chart). The latest annual economic report by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the central banks’ bank, devotes a whole chapter to the distributional effects of monetary policy. In the past central banks would argue that inequality was primarily the result of structural forces (automation, say, or globalisation) that lie beyond their mandate or their power. They have only one policy instrument, they would point out. They cannot set different benchmark interest rates for rich and for poor. And their workhorse economic models often featured a single “representative” household that was meant to stand in for everyone. A model will struggle to assess a policy’s impact on the distribution of income if there is, in effect, only one household to distribute to. |

Central Bankers Inequality, 2004 - 2021 |

In keeping with this tradition, the BIS warns its members not to overreach. Central banks best serve the cause of combating inequality by sticking to their traditional goals of curbing inflation, downturns and financial excess. Tacking on inequality as another objective could compromise the achievement of these aims. Monetary policy will find it harder to fight cyclical forces if it is too busy flailing against structural forces such as technology and trade.

Moreover, the age-old fight against inflation, recession and speculation is not necessarily inegalitarian. High inflation is often a regressive tax, harming those who rely on cash the most. “[I have] seen first-hand the havoc that high inflation can wreak on the poorer segments of society when I grew up in Argentina,” said Claudio Borio of the BIS in a recent speech. Fighting downturns is also an egalitarian endeavour. Recessions worsen inequality and inequality worsens recessions, in a cycle of “perverse amplification”, as Mr Borio puts it. Deeply divided societies suffer larger drops in output in bad times and respond more slowly to monetary easing. The effect of policy on the economy is impaired partly because the very poor cannot access credit, and therefore cannot borrow (and spend) more when interest rates are cut. Meanwhile, the very rich do not spend much more either, even though looser policy pushes up the prices of their assets.

There is, then, no need to give central banks a new, more egalitarian set of goals. But that leaves open the question of how central banks should meet those goals. Some approaches and tools may be better for social cohesion than others. And central banks might reasonably favour those that, all else equal, serve their mandate more equitably than others.

The Fed, for example, last year adopted a less trigger-happy interpretation of its inflation target. A side-effect of this approach should be lower income inequality. It will allow the Fed to find out whether people on the economic sidelines can become employable if hiring remains strong enough for long enough. To guide their thinking, central banks are turning to economic models that include “heterogeneous” households, a step beyond the “representative-agent New Keynesian” model (otherwise known as RANK). They also now have a bewildering variety of tools to choose from. Some buy equities, which are largely held by the rich. Others provide cheap funding to banks that lend to small firms. (The Bank of Japan does both.) Each tool will make a different contribution both to the level of spending and the distribution of income.

A tool of the many

Yet there are limits to what monetary policy alone can achieve. Even a central bank that sticks to its customary role, the BIS notes, may face awkward trade-offs, pitting income inequality against wealth inequality and inequality now versus inequality later. Bold monetary easing may lead to a more uniform distribution of income by preserving jobs. But it will boost the price of assets, increasing wealth inequality, at least in the short run. In addition, these expansive monetary policies can, the BIS argues, contribute to financial excesses that could go on to result in a deeper, more protracted recession in the future. And that would ultimately be bad even for income equality.

The BIS’s answer is to bring a wider range of policies to bear, including better financial regulation to curb speculative excesses and more responsive fiscal policy, where public finances permit. By spending more, governments allow central banks to buy less. Ben Bernanke, a former Fed chair much maligned by populist critics, put it this way: “If fiscal policymakers took more of the responsibility for promoting economic recovery and job creation, mon etary policy could be less aggressive.”

If central banks have worsened inequality in their efforts to rescue the economy it is partly because they have borne an unequal share of the job. With more help from fiscal policy, central banks will find it easier to take away the punch bowl before the tea party gets going. ■

This article appeared in the Finance & economics section of the print edition under the headline “Stabilité, libéralité, égalité”

Tags: Featured,newsletter