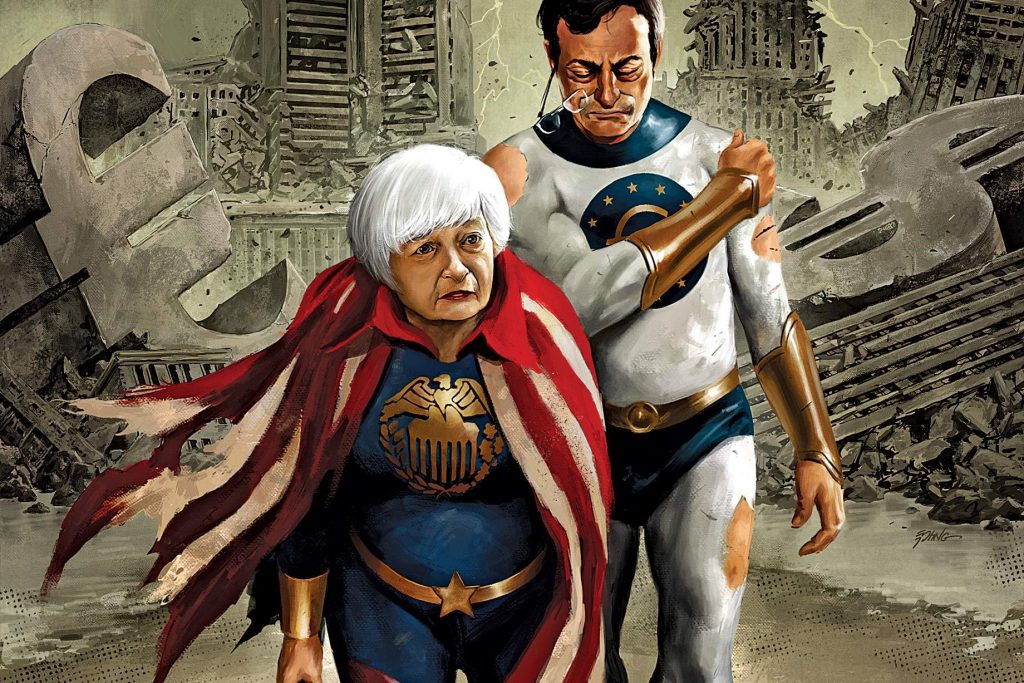

Consequences of Central Bank Policies The existing capital stock continues to be frittered away at the expense of savers and retirees. Nonetheless, central bankers don’t give a doggone about it. This, after all, is one consequence of roughly eight years of near zero interest rate policy. Central planning superheros, leaving a wasteland behind… Image credit: Steve Epting 30 year bond yield Another related consequence is that the pricing equilibrium of capital markets has broken down. In particular, bond yields no longer reflect a market determined price of money established by the economy’s demand for credit. Hence, previously unfathomable interest rate movements are now happening with unwavering regularity. Presently, the yield on the 10-Year U.S. Treasury note is sliding into the abyss. On Wednesday a new record low yield of 1.34 percent was reached. This is the lowest historical yield we could find based on a review of 10-Year Treasury rate data going back to about 1870. The last time the interest rate cycle bottomed out was during the early 1940s. The low inflection point at that time was somewhere around 2 percent. Where and when rates will finally turn this time is anyone’s guess.

Topics:

MN Gordon considers the following as important: 30 year bond yield, Central Banks, Debt and the Fallacies of Paper Money, Featured, Janet Yellen, Larry Summers, newslettersent

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Mark Thornton writes Is Amazon a Union-Busting Leviathan?

Consequences of Central Bank PoliciesThe existing capital stock continues to be frittered away at the expense of savers and retirees. Nonetheless, central bankers don’t give a doggone about it. This, after all, is one consequence of roughly eight years of near zero interest rate policy. |

|

30 year bond yieldAnother related consequence is that the pricing equilibrium of capital markets has broken down. In particular, bond yields no longer reflect a market determined price of money established by the economy’s demand for credit. Hence, previously unfathomable interest rate movements are now happening with unwavering regularity. Presently, the yield on the 10-Year U.S. Treasury note is sliding into the abyss. On Wednesday a new record low yield of 1.34 percent was reached. This is the lowest historical yield we could find based on a review of 10-Year Treasury rate data going back to about 1870. The last time the interest rate cycle bottomed out was during the early 1940s. The low inflection point at that time was somewhere around 2 percent. Where and when rates will finally turn this time is anyone’s guess. In the meantime, who in their right mind is plowing their hard earned money into Treasuries at these negligible returns? Obviously, it’s better than the negative rate of return that Swiss 50-year bonds are yielding. But come on. Is it not conceivably possible, with the Fed’s desired 2 percent inflation target, that inflation could run-up above 1.34 percent at some time over the next decade? |

30 year bond yields are actually still slightly above their 1945 low. 10 year yields bottomed in 1942 if memory serves and are currently below those levels, but we couldn’t find a chart going back that far. In any case, the depression era and its aftermath – during WW II the Federal Reserve held yields at artificially low levels to enable financing of the war – is the only period in which bond yields fell to levels comparable to today’s. This is interesting, since we keep hearing that everything is fine with the economy – click to enlarge. |

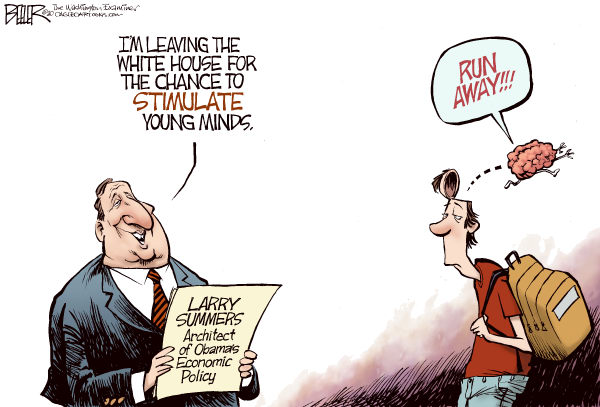

A Matter of Life or DeathBy way of full disclosure, we’ve been anticipating the conclusion of the great Treasury bond bubble for about 8 years – possibly longer. After a 25-year soft slow slide down from a peak above 15 percent in 1981, it only seemed logical that yields would bottom out around 2 percent and then resume a new, generation long uptrend. So far this hasn’t happened. Yields, in practice, have gone down…and then they’ve gone down some more. In hindsight, we’ve come to recognize that for a number of years we didn’t fully appreciate the significance of one very important component to this credit cycle. Moreover, it’s something that’s unlike the last credit cycle. Specifically, with a fiat based paper money system, and extreme central bank intervention, we didn’t account for just how far the limits of illogicality could push beyond what is honestly conceivable. Perhaps a better imagination was needed. Over the last few years we’ve made painstaking efforts to recalibrate our expectations. Namely, we’ve done away with them. But just because we have no expectations doesn’t mean we are indifferent. To the contrary, we are far from indifferent. We observe 10-Year Treasury yield movements with the same acute interest with which we observe an amorphous skin discoloration appearing on our torso. What do each day’s slight changes mean? Will they eventually become a matter of life or death? These are the questions. What are the answers? Larry Summers Wants to Give You a Free LunchOne possible suite of solutions came to us this week from Larry Summers, the former Treasury Secretary and a legend in his own mind. Summers, no doubt, is so smart he already knows the answers to questions before they are even asked. The world, as Summers perceives it:

|

|

According to Summers, with this low growth and low interest context, government debt levels no longer matter.

Somehow Summers already knows what interest rates will be more than a generation from now. And based on the ultra-low rates that Summers sees far out into the future, he believes expansionary fiscal policy can pay for itself. In other words, federal governments have free reign to massively increase deficit spending and run-up federal debts, because, on balance, the fiscal stimulus will pay for itself. Do you buy what Summers is selling? What if bond yields don’t go down over the next generation? What if they go up? Then, instead of being self-financing, fiscal stimulus would be self-destructing. Regardless, by our estimation he’s just promising something for nothing – that he can give you a free lunch. Alas, policies like these are what got us into this mess to start with. Sound money, and the just discipline that comes with it, makes more sense to us. But what do we know? We’re lacking in many of Summers’ unique qualifications. For example, unlike Summers, we’ve never lost $1.8 billion of other people’s money. |

Sometimes, the stimulus can become too much… Summers didn’t spend a lot of time as Harvard’s president – apparently he was only there long enough to deliver a devastating blow to its endowment. A few years ago, the US economy was only safe at certain times… and although Summers has less direct influence on policy today than he had back then, it is actually slightly worrisome that he has gone global with his advice-peddling. Cartoon by Nate Beeler |

Chart by: StockCharts

Chart and image captions by PT

M N. Gordon is the editor and publisher of the Economic Prism.