Increasing expectations that Germany’s Jens Weidmann will become the next ECB president are opening up gender equality issues. Change in the ranks of the central bank’s top brass is in the air.The Eurogroup has designated Spanish finance minister Luis de Guindos as candidate for the position of Vice President of the European Central Bank to succeed Vítor Constâncio in June 2018, for a non-renewable eight-year term. This nomination has increased expectations that Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann will become the next ECB President after Mario Draghi’s term ends in October 2019. This remains our baseline scenario, if only because we fail to see alternative candidates who would be politically acceptable to both Germany and France.If the ECB presidency goes to Germany, then Jens Weidmann is

Topics:

Frederik Ducrozet considers the following as important: ECB appointments, ECB gender equality, ECB presidency, Jens Weidmann, Macroview

This could be interesting, too:

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Big Splits

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Central Bank Halloween

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Widening bottlenecks

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Debt ceiling deadline postponed

Increasing expectations that Germany’s Jens Weidmann will become the next ECB president are opening up gender equality issues. Change in the ranks of the central bank’s top brass is in the air.

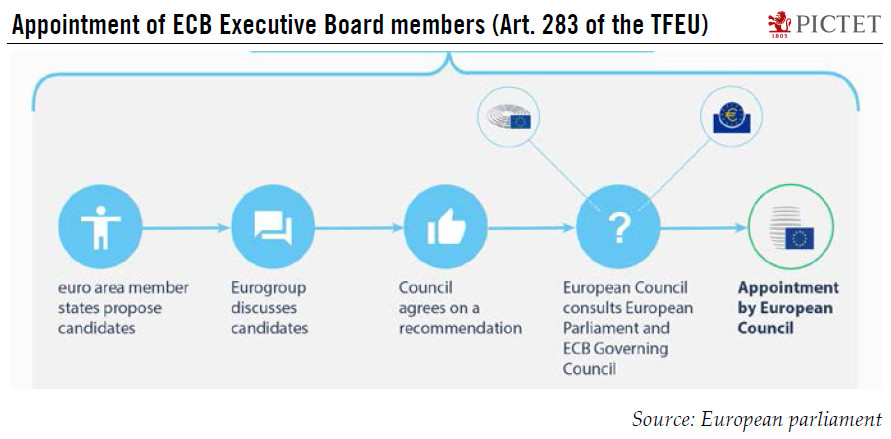

The Eurogroup has designated Spanish finance minister Luis de Guindos as candidate for the position of Vice President of the European Central Bank to succeed Vítor Constâncio in June 2018, for a non-renewable eight-year term. This nomination has increased expectations that Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann will become the next ECB President after Mario Draghi’s term ends in October 2019. This remains our baseline scenario, if only because we fail to see alternative candidates who would be politically acceptable to both Germany and France.

If the ECB presidency goes to Germany, then Jens Weidmann is a great choice, in our humble opinion. He is a highly respected economist and a pragmatist. Despite his opposition to ECB’s unconventional measures in the past few years, he has made sure that the cohesion of the Governing Council was preserved. A Weidmann-led ECB might well become slightly more hawkish, but continuity and gradualism would likely prevail under the influence of the Council and the staff. However, we see a number of complications that could potentially derail a Weidmann presidency.

In particular, Weidmann’s nomination would require Sabine Lautenschläger, the only woman on the Executive Board, to resign. The ECB has a gender imbalance, with only one woman sitting on the Executive Board and only two on the whole Governing Council. Change is overdue, especially if Jens Weidmann is to become ECB president in 2019. The ECB’s poor track record in terms of gender equality suggests that more women could make it to the Executive Board, with four of the six seats to be replaced by the end of 2019, forcing politically difficult choices on some member states. If no political agreement can be reached, then another candidate could be chosen as ECB president, either from France or, more likely, from a smaller country.

All in all, if a Weidmann-led ECB seems probable, it is not a done deal either. He still has a few hurdles to pass. The broader political context of European elections and nominations may well result in last-minute compromises and potential surprises.

A change in ECB leadership does not necessarily imply a change in monetary policy. We think gradualism will prevail over the foreseeable future in order to secure the ECB’s achievements under Draghi’s presidency. But markets will likely remain extremely sensitive to change at the top as the ECB moves toward policy normalisation.