Published: Monday July 24 2017Most people say they want to keep their personal information private, according to Professor Leslie John of Harvard Business School, but in practice they will reveal it for often trivial reasons or to win the approval of others.Privacy is an issue of great sensitivity in a digital age. Many people go to considerable lengths to protect their personal information from online access by strangers, commercial enterprises and public bodies. And users of most social media have to sign up to complex agreements setting out their rights to privacy and how the companies can use their personal information.Yet very few people read the lengthy privacy statements before signing away rights to the highly confidential information they provide online. And in practice, it can

Topics:

Perspectives Pictet considers the following as important: Cyber security, Digital security, In Conversation With, Online data security, Pictet Report Summer 2017, The Privacy Paradox

This could be interesting, too:

Perspectives Pictet writes House View, October 2020

Perspectives Pictet writes Weekly View – Reality check

Perspectives Pictet writes Exceptional Swiss hospitality and haute cuisine

Jessica Martin writes On the ground in over 80 countries – neutral, impartial and independent

Most people say they want to keep their personal information private, according to Professor Leslie John of Harvard Business School, but in practice they will reveal it for often trivial reasons or to win the approval of others.

Privacy is an issue of great sensitivity in a digital age. Many people go to considerable lengths to protect their personal information from online access by strangers, commercial enterprises and public bodies. And users of most social media have to sign up to complex agreements setting out their rights to privacy and how the companies can use their personal information.

Yet very few people read the lengthy privacy statements before signing away rights to the highly confidential information they provide online. And in practice, it can be very easy to persuade people to disclose information which is better kept private. In 2014, for example, an installation artist called Risa Puno extracted sensitive personal data such as fingerprints, driver’s licence numbers and mother’s maiden names from 380 New Yorkers in return for offering them a cookie – even though she refused to say what she would use it for.

Professor Leslie John, an associate professor at Harvard Business School, calls these contrasting aspects in the psychology of confidentiality and disclosure the ‘Privacy Paradox’.

“In the abstract, people say they care about privacy and oppose threats to the confidentiality of online information and private messages. But in practice, their behaviour suggests otherwise, partly because it is so difficult to put a precise figure on the material value of privacy and the damage caused by breaches. As a result, privacy isn’t top of mind and people’s willingness to reveal confidential information can be affected by seemingly trivial factors like the offer of a cookie.”

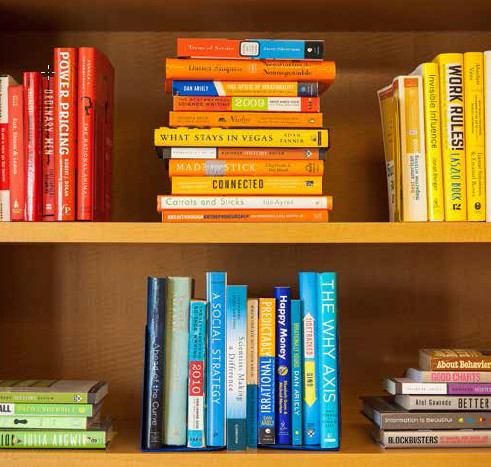

Prof John teaches MBAs and people in executive education courses at Harvard Business School. She also carries out research into how people make decisions in fields such as healthy eating and personal privacy. Those decisions are often believed to be made rationally, but her research reveals irrational decision-making processes, of which the Privacy Paradox is an example.

At the heart of such paradoxes is the fact that humans have conflicting motives when making decisions. They have a sincere desire for privacy, which establishes boundaries that are important to them in various ways. But they also know that disclosure of personal information can make other people like them more, because it is a key part of forging relationships.

Other researchers have demonstrated this aspect of human nature. Pairs of strangers were given lists of questions to ask each other, in order to see how much the answers affected their opinions of each other. This found that the more their answers disclosed personal information, the more the other person liked them.

In another experiment, people were asked who they would choose if one applicant said on a job application form that the worst grade they had ever achieved in an exam was a fail and another chose the ‘no answer’ option. The result was that 89 per cent preferred the former – they recognised that the candidate who came clean was the worse candidate but thought them more trustworthy, and were suspicious of people who withhold information.

There is a similar reverse process: the more that people like a website or questionnaire because it appears fun, the more willing people are to disclose information about themselves and set aside privacy considerations.

“Facebook heightens the desire to divulge in a variety of ways that make you want to share,” she says. “The more people see others sharing a lot, the more they are prepared to divulge about themselves. Meanwhile the website’s privacy settings are constantly changed and typically buried under several layers of menus, making it hard for users to review them.”

“Another factor that encourages disclosure is that there are often immediate and tangible benefits. As soon as you post on Facebook, you get feedback such as “likes” and comments, which psychology tells us is a form of conditioning that will encourage you to share more.”

“The dangers of sharing online are much vaguer. If compromising pictures are shared, future employers might see them some time in the future, but you don’t know who those employers are, or whether they’ll find them, or what the consequences will be. There is no clear link between your indiscretion and any bad outcome.”

Social media companies have strong motives to get as much information out of customers without alarming them, Professor John adds. It brings in more traffic, and more personal information – both of which can help in attracting advertising.

Another research project explored how willing people were to pay attention to privacy policies. Some companies give prominence to good policies, such as setting out restrictions on how they will use personal information. Others do not mention their privacy policies on order forms – an example is a company selling a car GPS system which has ‘additional features’ that effectively spy on the driver. “Sometimes, people are more likely to buy things from companies which do not mention privacy policies. Far from reassuring consumers, making such policies salient seems to set off alarm bells!”

A new development in social media which might help avoid postings such as embarrassing photos coming back to haunt people in later life is to make online sharing temporary. SnapChat, for example, deletes postings after 10 seconds – and while they can be saved by screen-grabs, it is not easy.

“But if an embarrassing photo vanishes, the impression it made on the recipient may not,” says Professor John.

“And that impression can be shared on social media, which might not have happened if the photo hadn’t been deleted.”

“To test the impact of a deleted image, we asked people to take selfies and share them online, some to be permanently visible and others only temporarily. They were more likely to take and share indiscreet selfies if told they were temporary, yet viewers thought that those who had taken racier photographs had worse judgment – even if they were quickly deleted. In other words, the character of the photo creates an impression, even if shared only temporarily.”

People are spending more time shopping, gaming and socialising online, at a time when data-gathering technology is becoming ever more sophisticated. Yet people still divulge sensitive personal information that can be of enormous value to firms and to more malign hackers. The Privacy Paradox suggests that more needs to be done to help people understand the value of privacy and how easy it is to part with sensitive information, while recognising the value of sharing appropriate information in personal relationships.