Moody’s downgraded China’s sovereign rating last week. We believe the country is well equipped to deal with debt issues in the short term, but faces profound challenges in the longer term.Moody’s announced on 24 May that it had downgraded China’s long-term local currency and foreign currency issuer ratings to A1 from Aa3, due to its concerns about the rising debt in China. According to our estimate, China’s total debt amounted to Rmb203 trillion as of the end of 2016, equivalent to 261% of its nominal GDP. Rising indebtedness is probably one of the most serious challenges for Chinese economy faces in the medium to long term.However, in the short term, we continue to hold the view that the probability of a financial crisis in China remains low, particularly as some recent developments in

Topics:

Dong Chen considers the following as important: China credit rating, China financial risks, Chinese debt, Chinese indebtedness, Macroview

This could be interesting, too:

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Big Splits

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Central Bank Halloween

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Widening bottlenecks

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Debt ceiling deadline postponed

Moody’s downgraded China’s sovereign rating last week. We believe the country is well equipped to deal with debt issues in the short term, but faces profound challenges in the longer term.

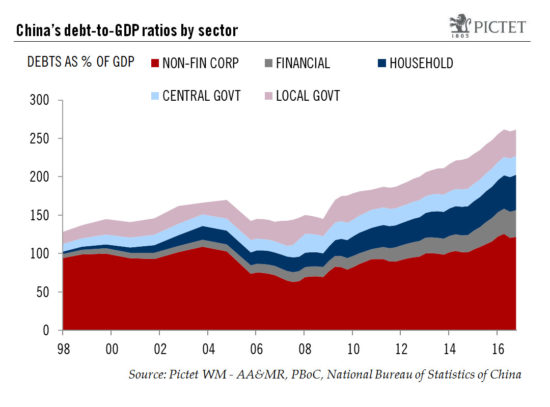

Moody’s announced on 24 May that it had downgraded China’s long-term local currency and foreign currency issuer ratings to A1 from Aa3, due to its concerns about the rising debt in China. According to our estimate, China’s total debt amounted to Rmb203 trillion as of the end of 2016, equivalent to 261% of its nominal GDP. Rising indebtedness is probably one of the most serious challenges for Chinese economy faces in the medium to long term.

However, in the short term, we continue to hold the view that the probability of a financial crisis in China remains low, particularly as some recent developments in China have led to a short-term stabilisation in the country’s debt situation.

First, the debt-to-GDP ratio for the non-financial corporates has stopped rising, and indeed has actually declined since Q2 2016. Second, the Chinese government started to implement a local government debt swap program in 2015. While the debt swap program in itself does not reduce the amount of debt, it greatly extends the maturity of public debt, by an average of three to five years. Third, in response to the surge in household leverage in 2016 due to the property boom, the government has taken increasingly tough measures to curb housing speculation.

In the longer term, however, structural reforms and reduced reliance on stimulus will be needed to really solve China’s debt problem. Rapidly rising debt does undoubtedly poses serious challenges to the Chinese economy, with respect to misallocation of capital and rising risk of financial disruptions.

Ultimately, rapid credit creation in China is a result of government efforts to stimulate growth through monetary and fiscal easing, especially after the global financial crisis. To reduce the speed of debt accumulation, the Chinese government will have to stop boosting the economy through stimulus, at least gradually. By extension, this means lower rates of growth. However, a sharp deceleration of the economy, particularly in nominal terms, could lead to the bursting of the credit bubble, which would be extremely destructive. The government therefore faces a very fine balance between growth and deleveraging. This balance will not be easy to maintain.