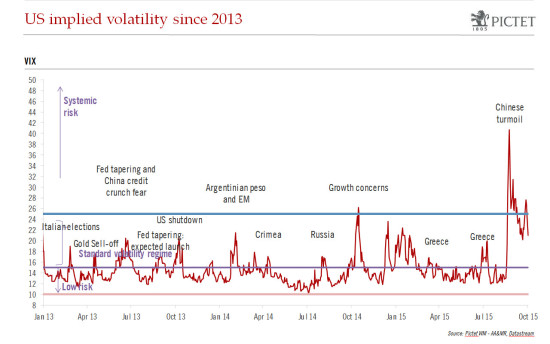

After a long period when market volatility was relatively subdued, it has risen sharply this year. The Vix, a widely used measure of equity-market volatility, was in a systemic risk regime for 15 days this year, compared with just two days in 2014 and none at all in 2013, as shown by the chart below. This year’s experience of volatility is still not extensive in a historical comparison, but it still represents a marked change from very subdued conditions in the previous two years. What explains the change? Higher market volatility at present is partly the result of low visibility on economic growth and earnings. However, a major factor is also the divergent and uncertain monetary policies of central banks. Central banks are in fact keen to limit market volatility, because they want to preserve the wealth effect created by quantitative easing (QE) and keep low financing costs down, in order to support economic recovery. For this reason they maintained ultra-low interest rates for an unusually extended period after the crisis of 2008-09, and developed ‘forward guidance’ to telegraph their intentions to markets. This rationale also underlies the emerging implicit new monetary policy style of Asymmetric Asset Price Targeting that seeks to put a floor under asset prices—as we have previously explained[1].

Topics:

Christophe Donay considers the following as important: Macroview

This could be interesting, too:

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Big Splits

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Central Bank Halloween

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Widening bottlenecks

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Debt ceiling deadline postponed

After a long period when market volatility was relatively subdued, it has risen sharply this year.

The Vix, a widely used measure of equity-market volatility, was in a systemic risk regime for 15 days this year, compared with just two days in 2014 and none at all in 2013, as shown by the chart below. This year’s experience of volatility is still not extensive in a historical comparison, but it still represents a marked change from very subdued conditions in the previous two years. What explains the change? Higher market volatility at present is partly the result of low visibility on economic growth and earnings. However, a major factor is also the divergent and uncertain monetary policies of central banks.

Central banks are in fact keen to limit market volatility, because they want to preserve the wealth effect created by quantitative easing (QE) and keep low financing costs down, in order to support economic recovery. For this reason they maintained ultra-low interest rates for an unusually extended period after the crisis of 2008-09, and developed ‘forward guidance’ to telegraph their intentions to markets. This rationale also underlies the emerging implicit new monetary policy style of Asymmetric Asset Price Targeting that seeks to put a floor under asset prices—as we have previously explained[1]. However, central banks’ ambition to limit market volatility is currently under strain because their policies are both uncoordinated and increasingly uncertain.

First, central bank policies are still desynchronised. The US Federal Reserve (Fed) and the Bank of England (BoE) have ended QE and are poised to raise interest rates. By contrast, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) and the European Central Bank (ECB) continue with QE, and indeed are likely to expand it because of weak inflation and lacklustre economic growth. The PBoC is also loosening monetary policy, although through different tools than those employed by the BoJ and the ECB. Finally, emerging market central banks are caught between the need to cut interest rates in order to counteract weakening economic growth, and the need to tighten so as to reduce capital outflows as the first Fed rate rise approaches.

Second, there is uncertainty about central bank intentions. This is partly because low visibility is complicating their decision-making. This could be seen with the Fed’s attempts in September, while keeping rates on hold, to continue to telegraph a rate rise in 2015—only for weak employment data just a couple of weeks later to throw this into renewed doubt. It is also because, with the global economy weak, central banks are increasingly having to factor external economic conditions over which they have no control into their decision-making. The Fed again provides a good example, delaying a rate rise in September partly on the grounds of concerns about the impact of a slowdown in China—however, this adds another layer of uncertainty to markets’ assessments of Fed policy.

The result is confusion for markets and heightened volatility. This is unlikely to change in the near term. Central bank policies will remain desynchronised, since the ECB and the BoJ are still at a fairly early stage in their QE and are unlikely to follow the Fed and the BoE in tightening for some years yet. Low economic visibility is also set to persist—most notably, although data from China in the fourth quarter may calm immediate fears about an economic slump, China’s protracted economic transition is far from complete and its economy will take time to settle into a more stable trajectory—the country will therefore remain a source of instability for the global economy.

Therefore, on the one hand, central banks are broadly supportive of markets, which bodes well for further rises in equity prices. On the other hand, despite their best intentions, desynchronisation of central bank policies and uncertainty over the timing of policy moves mean volatility is set to remain high. This analysis supports our overweight position in DM equities, but also calls for continued robust diversification to reduce the impact of volatility on portfolios, which we achieve through US Treasuries and equity-like assets that are decorrelated with equities.

Christophe Donay

Head of Asset Allocation & Macro Research

Chief Strategist

[1] See Perspectives, June 2015, ‘Topic of the Month – A New Monetary Policy Style and Its Consequences’; also The Financial Times, 19 August 2015, ‘Overvalued Equities Can Keep Rising’.