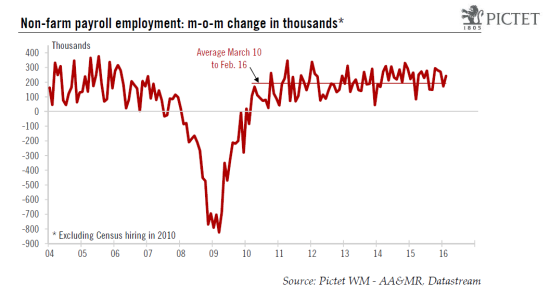

February’s employment report showed strong job gains and further reduction in labour market slack. Wage numbers were noticeably lower than expected and the average workweek fell markedly. Nevertheless, the US labour market remains quite healthy overall. Non-farm payroll employment rose by a robust 242,000 m-o-m in February, well above consensus expectations (195,000). Moreover, January’s figure was revised up (from 151,000 to 172,000), as was December’s number (from 262,000 to 271,000). Cumulative net revisions for the previous two months thus worked out at a positive 30,000. January’s relatively soft number was partly due to temporary dampening statistical factors. Some positive payback was therefore to be expected in February. In any case, job creations are very volatile in the short run (see chart above). Nevertheless, over the past three months, job creation averaged a robust 231,000, a number similar to what was registered on average in 2015 (228,000 per month), and slightly above the average since employment bottomed out in February 2010 (193,000). Between Q4 2015 and January-February 2016, employment grew by 1.9% annualised, a pretty solid rate considering economic activity probably grew by something similar over the same period.

Topics:

Bernard Lambert considers the following as important: Macroview

This could be interesting, too:

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Big Splits

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Central Bank Halloween

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Widening bottlenecks

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Debt ceiling deadline postponed

February’s employment report showed strong job gains and further reduction in labour market slack. Wage numbers were noticeably lower than expected and the average workweek fell markedly. Nevertheless, the US labour market remains quite healthy overall.

Non-farm payroll employment rose by a robust 242,000 m-o-m in February, well above consensus expectations (195,000). Moreover, January’s figure was revised up (from 151,000 to 172,000), as was December’s number (from 262,000 to 271,000). Cumulative net revisions for the previous two months thus worked out at a positive 30,000.

January’s relatively soft number was partly due to temporary dampening statistical factors. Some positive payback was therefore to be expected in February. In any case, job creations are very volatile in the short run (see chart above). Nevertheless, over the past three months, job creation averaged a robust 231,000, a number similar to what was registered on average in 2015 (228,000 per month), and slightly above the average since employment bottomed out in February 2010 (193,000). Between Q4 2015 and January-February 2016, employment grew by 1.9% annualised, a pretty solid rate considering economic activity probably grew by something similar over the same period. In any case, with the economy approaching full employment, a gradual slowdown in job creation should occur during the course of this year, hopefully accompanied by some improvement in productivity growth.

Unemployment rate stable at 4.9%

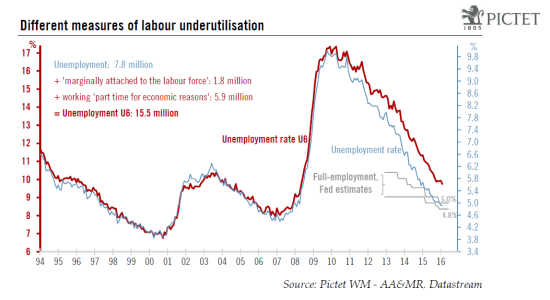

Meanwhile, the unemployment rate remained stable at 4.9% in February (4.92% before rounding), in line with consensus expectations. This rate represents a record eight-year low.

A more in-depth look at the household survey (which is the basis for the unemployment rate calculations) reveals that this stability reflects both robust employment growth and robust growth in the labour force. The employment measure of the household survey – in any case an often very volatile statistic – increased by a massive 530,000 m-o-m in February, whilst, at the same time, the size of the labour force rose by a marginally higher pace (555,000). The end-result was that the number of unemployed increased by a small 24,000 (555,000 minus 530,000). The marginal rise in unemployment was therefore linked to a sharp increase in the participation rate (from 62.7% in January to 62.9% in February), not to any kind of softness in employment gains.

At 4.9%, the unemployment rate is in the middle of the range that the Fed feels corresponds to full employment (4.8%-5.0%). Moreover, it is worth remembering that this latter range was lowered from 4.9%-5.2% as recently as December 2015.

The Fed has repeated many times that the unemployment rate probably underestimates the amount of resources available in the labour market. However, even if we consider a wider measure of unemployment, i.e. the U6 measure – which includes (1) employees working part-time, but who would prefer a full-time job, and (2) people who want a job, are available for work, have looked for a job sometime over the past 12 months, but did not do so during the current survey week and were therefore not counted as unemployed – it has fallen heavily over the past few years. Following some stabilisation at the end of 2015, this rate dropped once again last month, declining from 9.9% in January to 9.7% in February, marking a new low for this cycle. On this yardstick too, full employment does not look all that far away (see chart above).

Wages dropped m-o-m in February

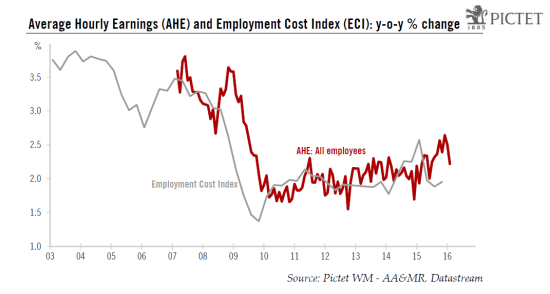

Meanwhile, average hourly earnings surprisingly fell by 0.1% m-o-m in February, a result noticeably below consensus estimates (+0.2%). However, this monthly decline follows a strong 0.5% monthly reading in January. Nevertheless, on a y-o-y basis, wage increases fell back from 2.5% in January to 2.2% in February. This series is quite volatile (see chart below), but according to these statistics, it seems that the pick-up in the pace of wage increases recorded over the course of the past year or so was significantly less pronounced than thought before today’s data. Moreover, the quarterly Employment Cost Index (ECI) – admittedly the most reliable measure of wages and salaries – is not pointing to any noticeable acceleration in wage increases, at least until Q4 2015, the most recent data available. In any event, we continue to expect wage increases to gradually pick up over the coming few quarters.

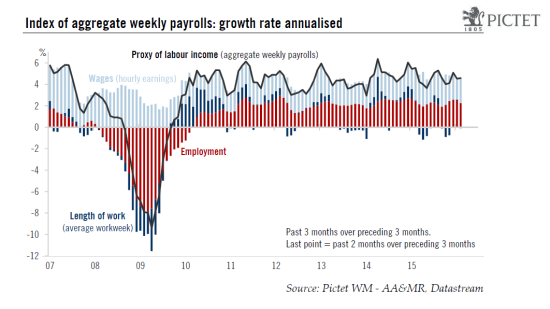

Surprisingly as well, the average workweek fell back markedly from 34.6 hours in January to 34.4 hours in February. In terms of total hours worked, a decrease of 0.2 hours is equivalent to some 700,000 jobs being lost. As a consequence, the index of ‘aggregate weekly payrolls’ (calculated as a product of aggregate hours worked and average hourly earnings) was quite disappointing. It fell by 0.5% m-o-m in February. However, this followed a strong 0.9% increase in January. The end-result was that this index – which is a good proxy for nominal household income coming in the form of private wages and salaries – still managed to grow by a healthy 4.6% annualised between Q4 and January-February, after +4.1% q-o-q in Q4 and +5.3% in Q3. This remains supportive for growth in household income in Q1, and for consumer spending.

Upbeat employment report

Today’s employment report showed strong payroll gains, a reduction in the labour market slack, but much softer-than-expected wage numbers. Meanwhile, economic data published over the past few weeks have generally shown some improvement, particularly on the consumption front. And core PCE inflation has picked up noticeably over the past few months, whilst monetary and financial conditions have eased back markedly since mid-January. In that context, the Fed will most probably keep a tightening bias. However, at the same time, monetary authorities also want to avoid any additional inappropriate tightening in financial conditions, particularly in an environment of very uncertain world growth prospects and fragile financial markets. Therefore, they will proceed very carefully. For the time being, our main scenario remains that the Fed will remain on hold in March, and then hike twice, once in June and once in December. However, the possibility that the FOMC will wait until September before acting is not negligible in our opinion.