You’ve heard of the virtuous circle in the economy. Risk taking leads to spending/investment/hiring, which then leads to more spending/investment/hiring. Recovery, in other words. In the old days of the 20th century, quite a lot of the circle was rounded out by the inventory cycle. Both recession and recovery would depend upon how much additional product floated up and down the supply chain. Deflation, too. On the contraction side, demand might fall off a bit for whatever reason(s), retailers getting stuck with a small inventory overhang. If they think it more than temporary, or don’t have the internal cash to finance it, the retail level scales back pushing inventory to wholesalers who then cut orders from producers. Serious enough, producers begin to cut back

Topics:

Jeffrey P. Snider considers the following as important: 5.) Alhambra Investments, currencies, economy, Featured, Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy, IHS Markit, ihs markit componsite pmi, Inventory, manufacturing, Markets, newsletter, services

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

You’ve heard of the virtuous circle in the economy. Risk taking leads to spending/investment/hiring, which then leads to more spending/investment/hiring. Recovery, in other words.

In the old days of the 20th century, quite a lot of the circle was rounded out by the inventory cycle. Both recession and recovery would depend upon how much additional product floated up and down the supply chain. Deflation, too.

On the contraction side, demand might fall off a bit for whatever reason(s), retailers getting stuck with a small inventory overhang. If they think it more than temporary, or don’t have the internal cash to finance it, the retail level scales back pushing inventory to wholesalers who then cut orders from producers.

Serious enough, producers begin to cut back their own activities, maybe to the point of forgoing new hires, perhaps laying off some workers already employed. Whatever necessary to equalize reduced order flow with cost structure and input utility.

When those layoffs hit, almost certainly it cuts further into demand (unemployed workers are far more careful and constrained consumers), more inventory stuck at retailers and wholesalers, then even fewer orders for producers who must sharpen their payroll axe all over again. This vicious cycle is what used to make up the balance of any recession.

But what if inventory first accumulates for other reasons?

It may be a different look to the cycle, though not necessarily an entirely different outcome. Suppose retailers (outside of automobiles) grow concerned about supply availability or shipping times. They might naturally react by boosting their current order flow if only to increase their chances some product makes it through the clogged shipping channels.

As that increased order flow unrelated to demand continues to move back through the supply chain, it probably would only make the transportation issues that much worse. It’s already a mess, and because it’s already a mess the entire supply chain tries to stuff more goods through it rather than less, rather than giving the system some time and space to work out enough kinks.

This, of course, would probably convince retailers to do it all over again, ordering even more they don’t need now or in the near future, now more desperate to try and raise their chances of receiving anything. More trouble for the shippers and so on.

Having intentionally over-ordered, and then over-ordered again (and again?), this time what happens when the logistics get more sorted out and then deliveries rather than trickle through come pouring out? This is the cyclical question for early 2022, not the unemployment rate.

Some companies have said they are ready, and have confidently declared how they will be able to manage holding such excessive levels of product. Maybe they can. But what happens to orders down at the lower reaches? Having received all this extra inventory, retailers and wholesalers aren’t going to keep double and triple ordering.

| Before even getting to demand considerations, the orders are going to drop and producers are going to become less busy. The inventory glut having been forwarded up to the retail level, maybe wholesale, it will have to be worked down over time.

This is where demand comes into it. If demand stays as robust as some might currently assume, it might not take that much time to normalize inventory, then get past the whole issue and imbalance with nothing much lost. And if demand isn’t as good, then we’re right back into the 20th century again. The way the supply bottlenecks of 2021 have worked out, there is going to be an inventory overhang at some point. When it does come about and how bad it will be, that’s really the demand question. There seems to be quite a bit of optimism about it, to the point of complacency while corporate CEO’s bark in the media instead about all the massive inflation they plan on throwing your way. Inflation today (therefore not inflation) but potentially too many goods tomorrow. However the inventory cycle manifests, the one thing each would have in common is its trough – disinflationary at the least. |

|

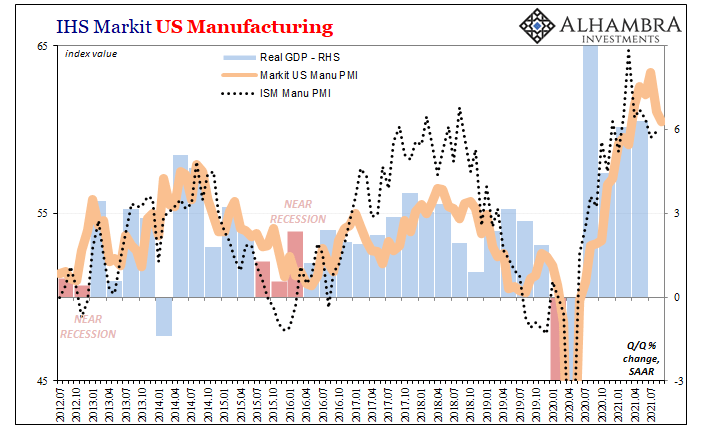

| Manufacturing PMI’s, for what it’s worth, remain elevated as if the upward segment of that unusual cycle remains relatively intact (note: ISM for September won’t be released for another week). With ships still stacking up on the US West Coast, this makes sense. Regardless of current levels of demand, these supply problems would only feed the imbalance for another month.

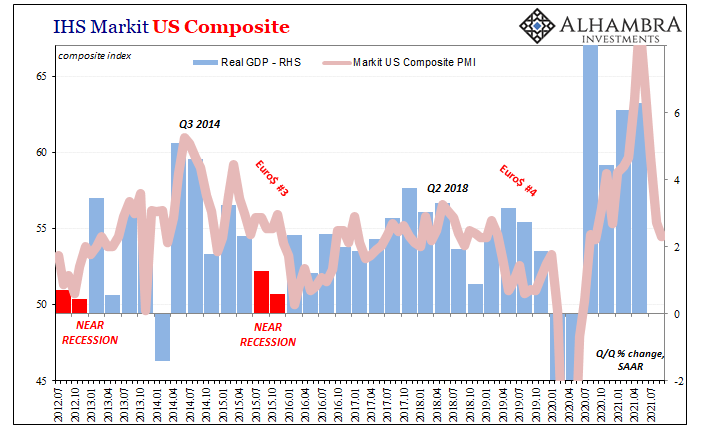

IHS Markit’s manufacturing index retreated again for the flash September 2021 estimate, but it remains above 60 therefore still in the post-2008 stratosphere. At 60.5 in the latest update, it is down, though, for the second month in a row since hitting the high of 63.4 back in July. And the index was 62.6 back in May, meaning it’s been four months treading. It is the services side which has materially declined, leading many to assume it must be due to delta COVID if goods flow is largely uninterrupted at the same time. Markit’s services PMI dropped to 54.4 in September from 55.1 in August, while its employment component fell back to just 50. This meant the composite, accounting for both manufacturing and services, declined to a very similar 54.5. Using this measure as a guide for possible GDP in Q3, that’s working down to a very disappointing 3% or less which might otherwise raise suspicions when it comes to the sustainability of demand. |

If this more serious setback really is pandemic-related, then thinking it a temporary one might keep up the order flow as well as the logistical nightmare. Then the artificial inventory cycle gets even more artificial.

It could very well be that manufacturing remains high because of inventory and not because current potential weakness is only about delta.

Should it turn out to be unrelated, or only somewhat attributable to renewed disease measures, then inventory stops being a pesky annoyance of shipping bottlenecks and potentially starts being more like its old self. While that wouldn’t necessarily mean recession in early 2022, even a substantial downturn (chances would have it globally synchronized) having yet fully recovered from the last two would be enough trouble.

Tags: currencies,economy,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,IHS Markit,ihs markit componsite pmi,Inventory,manufacturing,Markets,newsletter,services