This GIS 2021 Outlook series focuses on the opportunities that stem from the upheaval of the past year. Coronavirus vaccine distribution has begun, most probably marking the beginning of the end of the global health crisis. A receding pandemic will leave behind intertwined economic and fiscal challenges for countries around the world. Those that address rising debts with expenditure-based reforms in 2021 and eschew higher taxes can expect to benefit from faster and more robust recoveries. In the spring of 2020, I wrote that the pandemic’s fiscal policy would follow three general stages. First, governments expanded safety-net programs to support distressed businesses and unemployed workers due to government-imposed restrictions. The second phase, the attempt to

Topics:

hayek_admin considers the following as important: 6b.) Austrian center, 6b) Austrian Economics, blog, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Clemens Schneider writes Café Kyiv

Clemens Schneider writes Germaine de Stael

Clemens Schneider writes Museums-Empfehlung National Portrait Gallery

Clemens Schneider writes Entwicklungszusammenarbeit privatisieren

This GIS 2021 Outlook series focuses on the opportunities that stem from the upheaval of the past year.

Coronavirus vaccine distribution has begun, most probably marking the beginning of the end of the global health crisis. A receding pandemic will leave behind intertwined economic and fiscal challenges for countries around the world. Those that address rising debts with expenditure-based reforms in 2021 and eschew higher taxes can expect to benefit from faster and more robust recoveries.

In the spring of 2020, I wrote that the pandemic’s fiscal policy would follow three general stages. First, governments expanded safety-net programs to support distressed businesses and unemployed workers due to government-imposed restrictions. The second phase, the attempt to boost the recovery with traditional Keynesian stimulus spending, is now in full swing in several countries. Following these two significant expansions of discretionary budget authority, governments will eventually need to respond to the elevated deficits and ballooning debt that will be left behind. Many governments will resort to fiscal adjustments – tax hikes, spending cuts, or some combination of the two.

As we look to 2021 with an optimistic view of life after the pandemic, this report focuses on how governments can best navigate their increased debts. Appropriately designed fiscal adjustments can help boost domestic economic recoveries by reducing spending.

Current fiscal landscape

The initial fiscal aid provided by governments is unprecedented. The European Commission projects the aggregate government deficit of the euro area to rise from 0.6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019 to about 8.8 percent in 2020. (The Commission expects this aggregate deficit to shrink to 6.4 percent in 2021 and 4.7 percent in 2022.) Purposefully enacted discretionary measures make up about half of the increase. The remainder is from automatic stabilizers, such as unemployment benefits and decreased revenues due to the slower economy. In 2020, five countries – Belgium, Spain, France, Italy, and Romania – will have deficits above 10 percent of GDP.

In 2020, euro area debt-to-GDP is projected to increase by more than 15 percentage points, reaching almost 102 percent, up from 86 percent in 2019. Pre-Covid euro area debt-to-GDP ratios had steadily declined through 2019 since their peak in 2014. In 2022, debt is forecast to remain above 120 percent in Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain, and stay above 100 percent in Belgium, Cyprus, and France. The United States’ fiscal outlook was deteriorating before 2020. Now it is projected that debt levels will surpass the record highs set during World War II by 2023 and continue growing for the foreseeable future.

These projections understate the actual fiscal cost of the pandemic in two critical ways. First, they cannot account for future discretionary policy changes that could significantly increase budgetary costs. Second and more significantly, they assume no policy changes are made to current laws. In addition to increases in discretionary spending, euro area tax deferrals and other public guarantees amount to an additional 24 percent of GDP. Changes to current policies or private defaults could more than double current deficit projections, increasing fiscal pressures significantly.

Depressed revenues due to still rebounding economies and increased spending mean systematically elevated deficits, especially in the countries hit hardest by the coronavirus. In such circumstances, debt will continue to accumulate. Doing nothing to address large and rising debts will not be an option for many countries in 2021, even if interest rates remain low. Governments will be forced to either cut spending, increase taxes, or resort to some combination of the two.

Austerity opportunity

Politicians’ proclivity to spend now and tax later has led to countless historical examples of fiscal crises. The austerity plans that bring spending in line with revenues are never easy or costless. However, such fiscal adjustments become imminently necessary because debt accumulation is not a sustainable solution to chronic overspending.

Properly implemented fiscal adjustments, driven by spending cuts, do not have to be contractionary as predicted by many mainstream economic models. Expenditure-based fiscal adjustments, when implemented correctly, can be pro-growth in the short and long run. Reducing state spending can restore confidence in the government’s fiscal capacity and reassure taxpayers and investors that revenues will not need to increase to cover current unfunded expenditures.

In their 2019 book, Austerity: When It Works and When It Doesn’t, Alberto Alesina, Carlo Favero and Francesco Giavazzi summarize more than a decade of research on how countries address fiscal crises, outline case studies and present an empirical investigation of 16 countries over three decades, comprising 184 distinct austerity plans.

The researchers find those fiscal adjustments that focus primarily on reducing expenditures tend to be most successful at returning countries to economic growth trajectories while also lowering debt-to-GDP ratios. Relying on new or increased taxes to remedy fiscal imbalances deepens and prolongs economic recessions and usually fails to reduce debt-to-GDP ratios.

Large fiscal imbalances can create uncertainty for investors and consumers, slowing any economic recovery. When tax increases are expected, cutting taxes is not always necessary to activate a supply-side response resulting in additional economic activity. Merely removing the threat by constraining spending can boost private investment and consumption. This effect can be further enhanced if governments prioritize growth over deficit reduction by plowing spending reforms into strategic tax cuts. This simultaneously returns additional purchasing power to the private sector, further boosting growth and ultimately making deficit reduction easier as the economy accelerates.

Counterproductive tax increases

Raising taxes as a strategy to balance budgets or pay for new spending is less successful and more damaging to economic growth than cutting spending. The economic cost of tax increases is high and confirmed by a wide range of estimates that show they most often reduce GDP by two or three times the worth of the revenue increase.

Because tax hikes have steep economic costs, they are also less effective at reducing deficits. Mr. Alesina and his coauthors conclude that such fiscal adjustments are “self-defeating: they slow down the economy and do not reduce the debt ratio.” Relying on taxes to close the budgetary gap can create a vicious cycle: higher taxation slows down growth, which produces pressure to increase expenditure on countercyclical anti-poverty programs, necessitating still higher taxes to avoid a debt crisis.

Given the compelling evidence that tax increases harm recoveries, countries that opt for this strategy will become cautionary tales for others worldwide. France, Spain, Italy, and the UK have implemented new digital services taxes, and others are considering similar levies. Canada recently announced a 566 percent increase in its carbon tax over the next decade, and Spain is set to be the only country in Europe to hike its VAT in 2021 (the rate will increase for sugary drinks).

The good news is that a majority of other countries around the world, including most in the EU, have planned to extend lower VAT rates into 2021. Similarly, few countries have current plans to increase income, social security or other broad-based taxes in the year to come. This leaves the door open for governments to choose how they will address their rising debts in 2021 and beyond. Will they opt for tax increases or spending reforms?

Learning from history

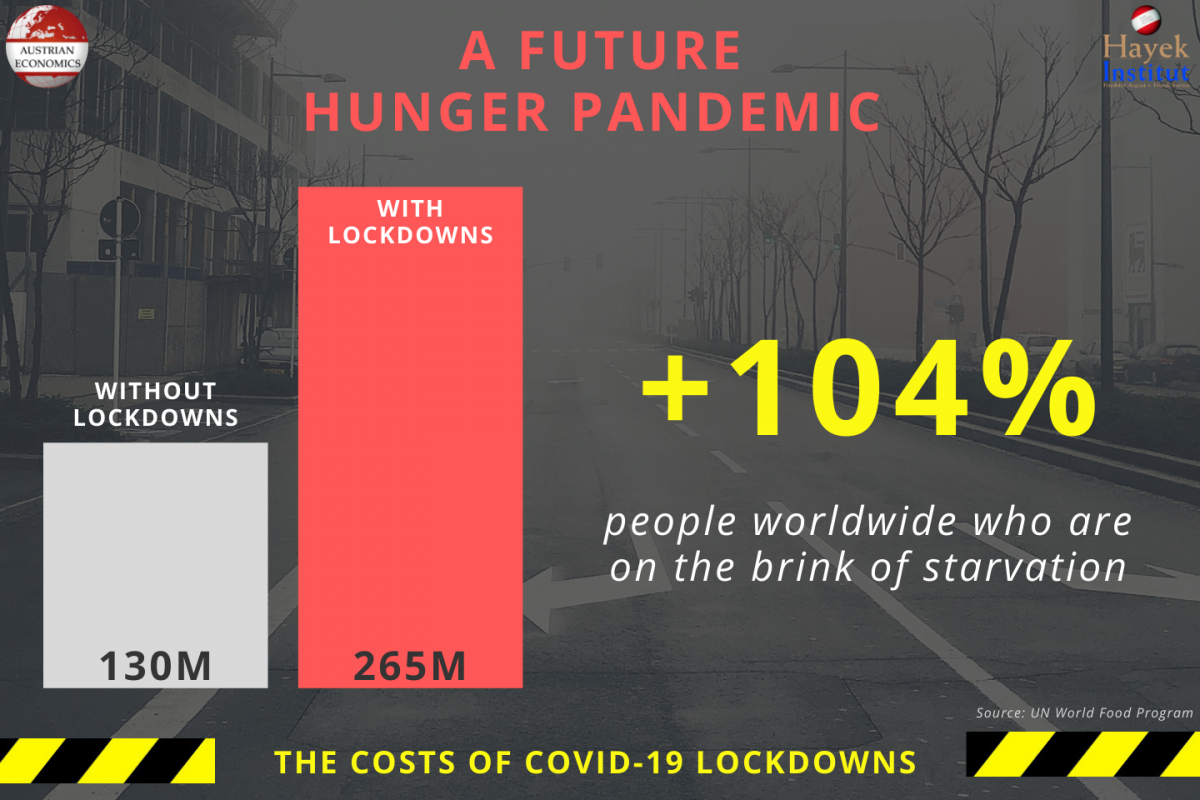

The initial response to this unprecedented global pandemic is mostly behind us. Some countries are beginning to embark on considerable stimulus efforts to jump-start their economies following the rollout of vaccines. Try as they might, governments cannot spend their way back to economic prosperity. By directing fiscal capacity at the economic hardship caused by shutdown orders that do not successfully suppress the virus, lawmakers often ignore the more complicated work of increasing testing capacity, streamlining drug approvals and ramping up vaccine distribution.

Large new spending packages are primarily a distraction and will likely result in little more than additional public debts. How governments respond to those will be crucial. The history of economic booms and busts shows that tax increases deepen and prolong the economic slowdown. Scaling back expenditures and keeping taxes low will set countries on the paths to sustainable economic recovery.

The fiscal response to the current crisis will likely be highly divergent. Many countries, like Luxembourg, Estonia, and Bulgaria, which already have smaller, more efficient governments and those like Sweden and Denmark, which have some of the highest taxes, but well-run fiscal unions, are projected to keep debt and deficits low in the coming years. These countries likely will not need dramatic changes in fiscal policy. Those on the other end of the spectrum, such as Spain, France, Italy and the U.S., have two paths they can take. Delaying fiscal reform or increasing taxes will make economic recovery more challenging. Decisive action to curb expenditures in 2021 can set up countries around the world for success in the years to come.

Tags: Blog,Featured,newsletter