In the New York Times on September 8, 2020, Paul Krugman wrote that The CARES Act, enacted in March, gave the unemployed an extra 0 a week in benefits. This supplement played a crucial role in limiting extreme hardship; poverty may even have gone down. For Krugman and many economic commentators, it is the duty of the government to support the economy whenever it falls into an economic slump. Following in the footsteps of John Maynard Keynes, most economists hold that one cannot have complete trust in a market economy, which is seen as inherently unstable. If left free the market economy could lead to self-destruction. Hence, there is the need for governments and central banks to manage the economy. Successful management in the Keynesian framework is done by

Topics:

Frank Shostak considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

In the New York Times on September 8, 2020, Paul Krugman wrote that

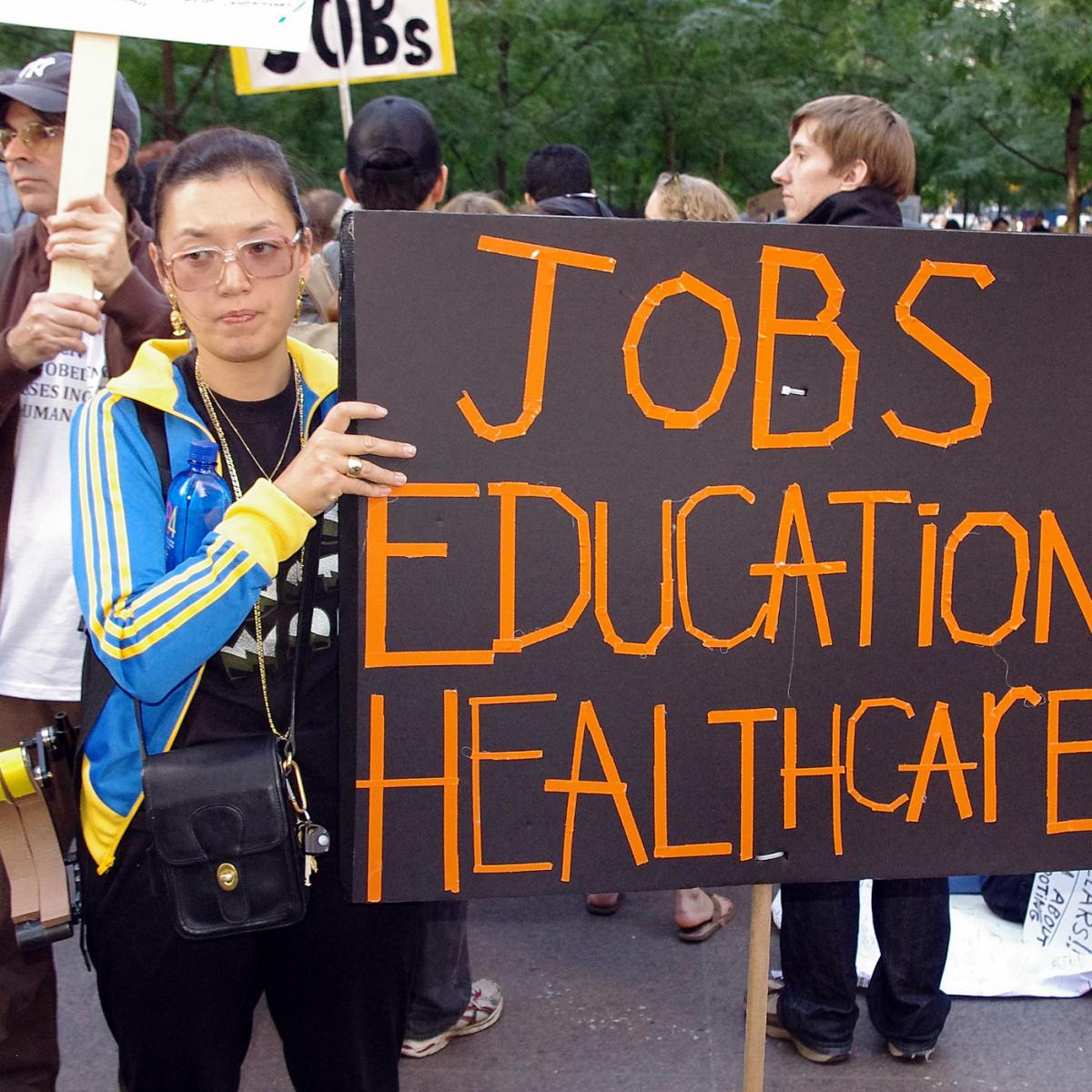

The CARES Act, enacted in March, gave the unemployed an extra $600 a week in benefits. This supplement played a crucial role in limiting extreme hardship; poverty may even have gone down.

For Krugman and many economic commentators, it is the duty of the government to support the economy whenever it falls into an economic slump. Following in the footsteps of John Maynard Keynes, most economists hold that one cannot have complete trust in a market economy, which is seen as inherently unstable. If left free the market economy could lead to self-destruction. Hence, there is the need for governments and central banks to manage the economy. Successful management in the Keynesian framework is done by influencing overall spending.

It is spending that generates income. Spending by one individual becomes income for another individual according to the Keynesian framework of thinking. Hence the more that is spent, the better things will be. What drives the economy then is spending. If during a recession, consumers fail to spend then it is the role of the government to step in and boost overall spending in order to grow the economy.

In the Keynesian framework of thinking, the output that an economy can generate with a given pool of resources (i.e., labor, tools and machinery, and technology) without causing inflation is labeled as potential output. Hence the greater the pool of resources, all other things being equal, the more output can be generated.

If for whatever reason the demand for the produced goods is not strong enough, there will be an economic slump, because inadequate demand for goods leads to only a partial use of existent labor and capital goods. In this framework, then, it makes a lot of sense to boost government spending in order to strengthen demand and eliminate the economic slump.

Funding and Economic Growth

What is missing in the Keynesian story is the matter of funding. For instance, a baker produces ten loaves of bread and exchanges them for a pair of shoes with a shoemaker. In this example, the baker funds the purchase of shoes by producing the ten loaves of bread.

Note that the bread maintains the shoemaker’s life and well-being. Likewise, the shoemaker has funded the purchase of bread by means of shoes that maintain the baker’s life and well-being.

Now, let us say the baker has decided to build another oven to be able to increase the production of bread. In order to implement his plan, the baker hires the services of the oven maker. He pays the oven maker with some of the bread he is producing. The building of the oven is supported by the production of bread. If for whatever reason the bread production were disrupted, the baker would not be able to pay the oven maker. As a result, the making of the oven would have to be abandoned.

From this simple example, we can infer that what matters for economic growth is not just tools and machinery and the pool of labor, but an adequate flow of consumer goods that maintain individuals’ life and well-being.

Now, even if we were to accept the Keynesian framework that the potential output is above actual output, it does not follow that the increase in government outlays and loose monetary policy will lead to an increase in the economy’s actual output. It is not possible to lift the overall production without the necessary support from the flow of real savings.

We have seen that by means of a consumer good—the bread—the baker was able to fund the expansion of his production structure. Similarly, other producers must have saved consumer goods—real savings—to fund the purchase of the goods and services they require.

Note that the introduction of money does not alter the essence of what funding is. Money is just the medium of exchange. It is only employed to facilitate the flow of goods; it cannot replace consumer goods required to support individuals’ life and well-being.

Government Is Not a Wealth Generator

The government as such does not produce any real wealth, so how can an increase in government outlays revive the economy? Various individuals who are employed by the government expect compensation for their work. The only way it can pay these individuals is by taxing others who are still generating real wealth. By doing this, the government weakens the wealth-generating process and undermines prospects for economic recovery. (We ignore here borrowings from foreigners).

An important factor that makes the fiscal and monetary stimulus appear to “work” is that the flow of real savings is large enough to support, i.e., fund, government-sponsored activities while still permitting a positive rate of growth in the activities of real wealth generators.

If, however, the flow of real savings is decreasing, then regardless of any increase in government outlays and monetary pumping by the central bank, overall real economic activity cannot be revived. In this case the more government spends and the more the central bank pumps, the more will be taken from wealth generators, weakening any prospects for a recovery.

When loose monetary and fiscal policies divert bread from the baker, he will have less bread at his disposal. Consequently, the baker will not be able to secure the services of the oven maker. As a result, it will not be possible to boost the production of bread, all other things being equal.

As the pace of loose policies intensifies, a situation could emerge whereby the baker will not have enough bread left to even sustain the workability of the existing oven. The baker will not have enough bread to pay for the services of a technician to maintain the existing oven in good shape. Consequently, the production of bread will actually decline.

Similarly, other wealth generators, because of the increase in government outlays and monetary pumping, will have less real savings at their disposal. This in turn will hamper the production of their goods and services and will retard and not promote overall real economic growth.

As one can see, not only does the increase in loose fiscal and monetary policies not raise overall output, but, on the contrary, it leads to a weakening in the process of wealth generation in general. According to Ludwig von Mises in Human Action,

there is need to emphasize the truism that a government can spend or invest only what it takes away from its citizens and that its additional spending and investment curtails the citizens’ spending and investment to the full extent of its quantity. (p. 744)

Why Economic Cleansing Promotes Economic Growth

The conventional thinking headed by Krugman presents economic adjustment—also labeled as “economic recession”—as something terrible, even the end of the world. In fact, economic adjustment is not menacing or terrible; from an economic point of view, it is nothing more than a time when scarce resources are reallocated in accordance with consumers’ priorities.

Allowing the market to make the allocations always leads to better results. Even the founder of the Soviet Union, Vladimir Lenin, understood this when he introduced the market mechanism for a brief period in March 1921 to restore the supply of goods and prevent economic catastrophe. Yet most experts these days cling to the view that the market cannot be trusted in difficult times. The collapse of the Soviet Union’s centralized system is the best testimony one can have that controls do not work.

A better way to fix economic problems is to allow entrepreneurs the freedom to allocate resources in accordance with people’s priorities. In this sense, the best stimulus plan is to allow the market mechanism to operate freely. Allowing the market to do the job will result in some activities disappearing all together while other activities will in fact be expanded.

Loose fiscal and monetary policies are not going to rescue the economy, but will rescue activities that are generating products that are on the low priority lists of consumers, i.e., consumers cannot afford them. Loose fiscal and monetary policies will sustain waste and promote inefficiency, draining resources from activities that are generating wealth.

Why Doing Nothing Is the Best Policy

Decades of reckless monetary and fiscal policies have severely depleted the pool of real savings. More loose policies cannot make the current situation better. On the contrary, such policies only further delay the economic recovery.

Contrary to the assertions of Krugman and other commentators, the best economic policy is for the Fed and the government to do nothing as soon as possible. By doing nothing the Fed and the government will enable wealth generators to accumulate real savings. (The policy of doing nothing will force various activities that add nothing to the pool of real savings to disappear. This will make the lives of wealth generators much easier). As time goes by the expanding pool of real savings will lay a foundation for the further expansion of various wealth-generating activities. The sooner the Fed and the government remove themselves from the economy, the sooner an economic recovery will emerge.

Conclusion

Contrary to Krugman and other pundits, neither the Fed nor the government’s loose monetary and fiscal policies can cause an expansion in the pool of real savings. On the contrary, loose policies only weaken the process of real savings formation, thereby weakening prospects for a sustained economic expansion.

If loose monetary and fiscal policies could set in motion economic growth, then by now all the poverty in the world would have been eradicated. The only reason why in the past loose monetary and fiscal policies appeared to have been effective is because the pool of real savings was expanding. Once this pool becomes stagnant, or starts declining, the illusion of the effectiveness of these policies will be shattered. The more aggressive the fiscal and monetary policies, the worse the economic conditions will become.

Now if the pool of real savings is still okay, then there is no need for the Keynesian policies to revive the economy—the pool will do it. If the pool is in trouble, the Keynesian policies will only make things much worse, and we could end up in a prolonged economic depression. Hence, the best, policy is to do nothing.

Tags: Featured,newsletter