If indeed this inflation hysteria has passed, its peak was surely late January. Even the stock market liquidations that showed up at that time were classified under that narrative. The economy was so good, it was bad; the Fed would be forced by rapid economic acceleration to speed themselves up before that acceleration got out of hand in uncontrolled consumer price gains. On February 1, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow tracking model was moved up to predict 5.4% GDP growth in Q1. It was the perfect top for the hysteria; a blowout estimate that was every bit as hollow as the narrative. First, the narrative: The economy is on track to put up blockbuster growth numbers in the first quarter, according to the latest forecast

Topics:

Jeffrey P. Snider considers the following as important: consumer spending, currencies, economic boom, economy, Featured, Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy, gdpnow, inflation, inflation hysteria, Markets, newsletter, Retail sales, s-curve, The United States, U.S. Retail Sales

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

If indeed this inflation hysteria has passed, its peak was surely late January. Even the stock market liquidations that showed up at that time were classified under that narrative. The economy was so good, it was bad; the Fed would be forced by rapid economic acceleration to speed themselves up before that acceleration got out of hand in uncontrolled consumer price gains.

On February 1, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow tracking model was moved up to predict 5.4% GDP growth in Q1. It was the perfect top for the hysteria; a blowout estimate that was every bit as hollow as the narrative. First, the narrative:

The economy is on track to put up blockbuster growth numbers in the first quarter, according to the latest forecast from the Atlanta Fed…

If the forecast holds, it would be the best quarter since the Great Recession ended in 2009. The previous highest was third quarter of 2014, which hit 5.2 percent.

The GDP tracking model was, in the beginning, a good idea. To be able to predict the big aggregate in close to real-time was a considerable draw. Unfortunately, it has proven just as difficult as ever. Demonstrating over time instead that there is quite a bit of noise on these shorter timescales, it’s the very problem that led to the creation of GDP (derived from GNP before it) in the first place.

To be fair to CNBC, the outlet publishing the article quoted above, these flaws were pointed out in the article. In particular, GDPNow over the past year and a half has fallen frequent victim to the ISM and sentiment. According to the ISM and other PMI’s, the economy is booming in a way it hasn’t since the turn of the millennium. According to GDP, not even close. The Atlanta Fed’s model has trouble reconciling these vast differences.

Part of the problem especially in the latter stages of 2017 was the introduction of artificial elements in the aftermath of Harvey and Irma. For a project like GDPNow, the shorter scale for measurement meant a susceptibility to distortions. This is particularly true when carrying estimates of output from one quarter to start off the next.

For inflation hysteria, however, none of this mattered. The economy was if not yet booming just about to start.

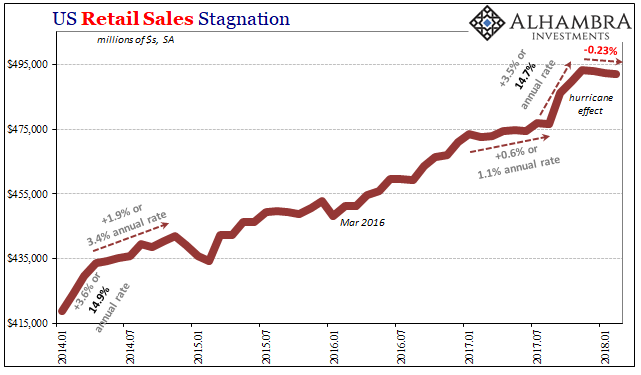

| Retail sales, for example, absolutely surged starting last September. What had been unusually weak (even for this economy) throughout the middle months of 2017 suddenly the US consumer was awake. For three months, retail sales (seasonally adjusted) jumped by 3.5%, an annual rate of 14.7%. It fed not just GDPNow’s baseline but fueled the hysteria.

Common sense is less charitable at times. The major problem, other than the obviousness of the timing, was the scale of that acceleration. A boom is as much a process as a crash. As it builds, you can see the reasonable basis for a change in trend (almost always staring with income). It doesn’t just start at the flip of a switch. Retail sales, as many other economic accounts, appeared to do just that, however. There was a very weak economy and then out of nowhere there wasn’t. |

US Retail Sales, Jan 2014 - Mar 2018(see more posts on U.S. Retail Sales, ) |

| Since November, retail sales have now declined for the third month in a row through February 2018. Estimates for December have been reduced at each update since their initial release in January. The following first two months of 2018 have only elongated the giveback aftermath of the hurricanes’ aftermath. |

US Retail Sales, Jan 2014 - Mar 2018(see more posts on U.S. Retail Sales, ) |

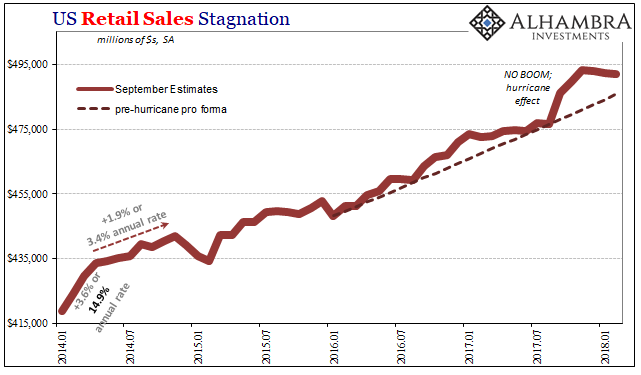

| The length of retrenchment suggests it’s too much for bad weather, or at least the typical mainstream excuse that somehow assigns winter as a cause for consumer pause. There was some heavy storms and snows, but there are always heavy storms and snows.

Not only was the hurricane distortion temporary, we are also likely seeing the emerging second part of Frederic Bastiat’s broken windows fallacy. While there was clearly a substantial gain in economic activity following the twin landfalls of Harvey and Irma, the bill for all that destruction is now coming due and is surely falling upon a wider segment than just those who fell within the hurricanes’ tracks. In addition, though it’s only two months so far, there obviously has been no boost due to tax cuts and bonuses, either. This is also unsurprising, representing more of the same hardened (meaning permanent, absent the mythical S-curve shift) consumer problems that have plagued the global economy since 2006. In short, without enormous debt supplement labor utilization and therefore incomes and wages are too low to support anything more than low level growth even at these “best” of times upturns (essentially a no-growth baseline when factoring the downturns). |

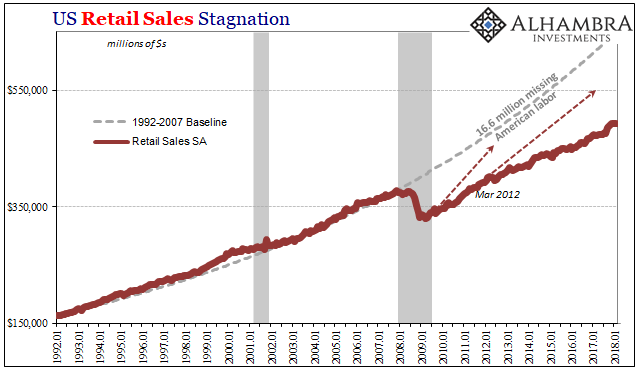

US Retail Sales, Jan 1992 - Mar 2018(see more posts on U.S. Retail Sales, ) |

| This hurricane cycle, for lack of a better term, is proving that fact once again. The economic problem is intractable, not something that will just disappear for whatever reasons one might wish to ascribe for tomorrow. This is the major problem with interpretation of these and other statistics; we have been conditioned to believe that economic growth just happens, and that if it is absent for any length of time it won’t be for much longer. |

US Retail Sales, Jun 2011 - Feb 2018(see more posts on U.S. Retail Sales, ) |

| Therefore, the longer it is absent the more assured many people (Economists, in particular) become that restoration just has to be close at hand. The idea that an economy can stagnate (depression) for a very long time is still a foreign one no matter how many times it has been re-affirmed since August 2007. This desperation forces the hype; to look to any small positive as if definitive on the matter even when it is otherwise easily explained as something like Harvey and Irma. |

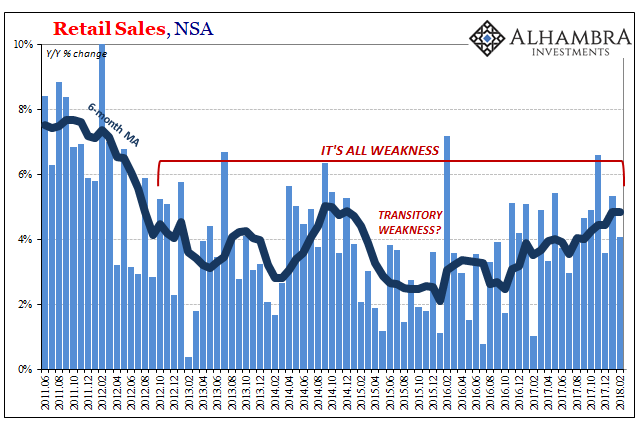

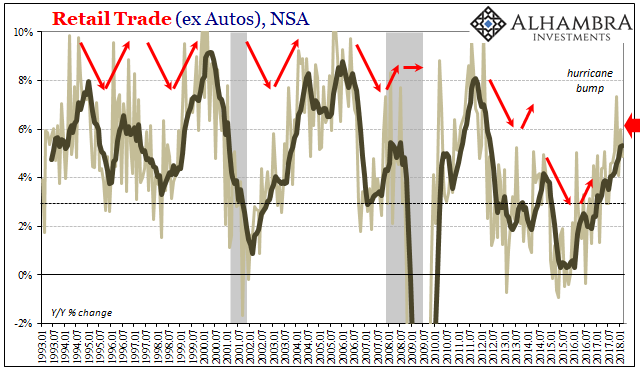

US Retail Trade, Jan 1993 - 2018 |

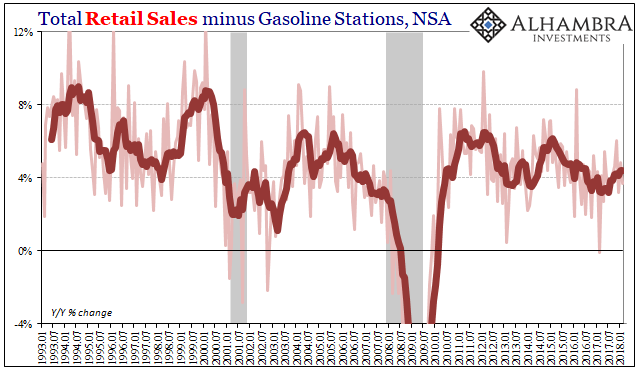

| For February 2018, retail sales unadjusted were up just 4.06%. That’s the same level of growth far too close to the recession 3% level prevalent since 2012. And those figures include the 3-month hurricane boost late last year. Worse, retail sales are up just 5.1% since February 2016, which was just about the bottom of that last downturn. Taking out sales of gasoline, retail sales were up just 3.7% year-over-year. |

US Retail Sales, Jan 1993 - 2018(see more posts on U.S. Retail Sales, ) |

As a result of this “unexpected” decline in retail sales, as well as the lack of acceleration in the CPI, GDPNow currently predicts Q1 GDP of just 1.9%. This latest reduction is primarily attributable to lowered expectations for Personal Consumption Expenditures; or, the same “residual seasonality” kind of first quarter that is both typical and all-too-easily explained.

What’s important about GDPNow is not its latest 1.9% prediction, rather it’s the broad variation between that low and the prior 5.4% high. Who knows what Q1 GDP might end up being? It is descriptive of the difficulties with not just economic measurements, but more so the economy itself.

As always, the question needs to be asked every time – what has changed? Time is definitive on this matter, just not in the way it is taken in the mainstream. If the answer is tropical weather, or tax cuts, then the return to weakness is nowhere near “unexpected.”

Tags: consumer spending,currencies,economic boom,economy,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,gdpnow,inflation,inflation hysteria,Markets,newsletter,Retail sales,s-curve,U.S. Retail Sales