Bundesrepublik Deutscheland Finanzagentur GmbH (German Finance Agency) was created on September 19, 2000, in order to manage the German government’s short run liquidity needs. GFA took over the task after three separate agencies (Federal Ministry of Finance, Federal Securities Administration, and Deutsche Bundesbank) had previously shared responsibility for it. On September 17, 2014, almost exactly fourteen years later, GFA managed to sell 2-year federal paper for the first time at a negative yield. Pricing at -0.07%, the streamlined success of the auction process was hardly the reason. The difference between September 2000, indeed all the Septembers before that year and the several after it, and September 2014 was that Septembers in 2008 and 2011 lay in between. Feeling no urge to digress, at this point, into why it is always the early autumn that seems destined to mark such occasions, at the time the newsworthy auction was described in the way it is always described. From the Wall Street Journal that day: Investors paid a hefty price for the privilege of buying German government debt Wednesday, in a fresh sign of how the European Central Bank’s monetary policies are upending the region’s bond markets. For mainstream outlets like WSJ, this was a good thing.

Topics:

Jeffrey P. Snider considers the following as important: Bank of Japan, bond market, bonds, Bund yields, Bunds, Central Bank, currencies, depression, economy, Euro, EuroDollar, eurodollar futures, Europe, Featured, Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy, France, Germany, Japan, Japan Government Bonds (JGB), JGB, JPY, lost decade, Markets, newsletter, Populism, QE, QQE, The United States, USD-CNY, Yield Curve

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Bundesrepublik Deutscheland Finanzagentur GmbH (German Finance Agency) was created on September 19, 2000, in order to manage the German government’s short run liquidity needs. GFA took over the task after three separate agencies (Federal Ministry of Finance, Federal Securities Administration, and Deutsche Bundesbank) had previously shared responsibility for it. On September 17, 2014, almost exactly fourteen years later, GFA managed to sell 2-year federal paper for the first time at a negative yield. Pricing at -0.07%, the streamlined success of the auction process was hardly the reason.

The difference between September 2000, indeed all the Septembers before that year and the several after it, and September 2014 was that Septembers in 2008 and 2011 lay in between. Feeling no urge to digress, at this point, into why it is always the early autumn that seems destined to mark such occasions, at the time the newsworthy auction was described in the way it is always described. From the Wall Street Journal that day:

Investors paid a hefty price for the privilege of buying German government debt Wednesday, in a fresh sign of how the European Central Bank’s monetary policies are upending the region’s bond markets.

For mainstream outlets like WSJ, this was a good thing. Lower interest rates, after all, make it cheaper for people and businesses to borrow, the very thing the ECB declared it was after. The nature of “stimulus” above the zero lower bound was unquestioned, but despite that there was a little unsettling feeling to dropping below it as far out as two years even if it was in Germany.

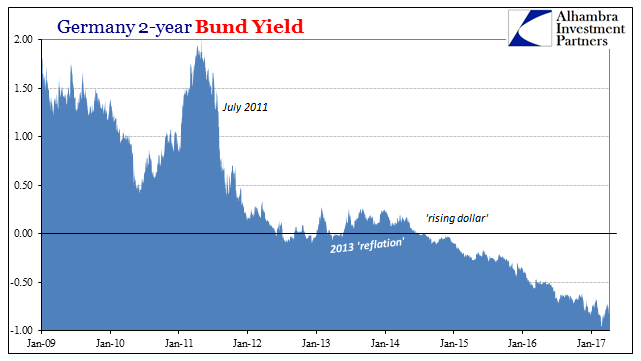

Just a few months ago, in late February 2017, the German 2s had reached truly ridiculous proportions, “yielding” just above -100 bps. At the time, the decay in yields was then put down as alarming, attributed to French election unease; from “stimulus” to populism fears in two and a half years. Suffice to write, there isn’t a whole lot about German bunds or bonds in general that makes sense to the mainstream accustomed to describing central banks that so easily get everything they want.

This fixation on the omniscience of monetary policy is the single biggest factor holding everything back. And in 2016 it took on different proportions; because central banks are getting out of the economy business and the economy remains as dark and unattractive as it is, the ultimate sagacity of the central banker must mean that the economy was itself unfixable. For if Mario Draghi or Ben Bernanke couldn’t do it, then no one can.

Removing ourselves from the absurdity of that idea, however, the bund and bond markets actually make perfect sense for a world just that upside down (subscription required).

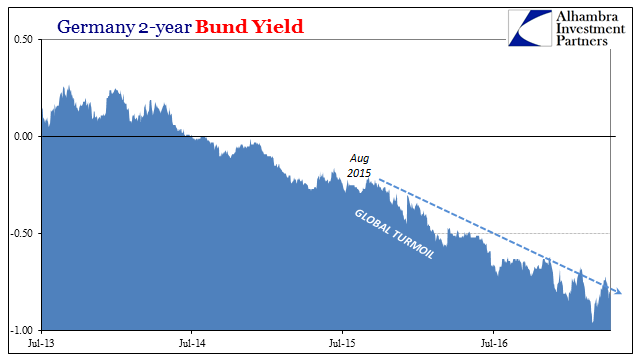

Nothing ever goes in a straight line, but the German 2s have come pretty close to achieving one dating back, unsurprisingly, to August 2015. |

Germany 2-year Bund Yield 2009-2017 |

Germany 2-year Bund Yield 2013-2017 |

|

| There wasn’t Brexit, Trump or le Pen back then, just the “unexpected” emergence of globally synchronized turmoil. To make matters worse, it was China that seemed to be at its center. Rather than realize the significance, instead the dollar world was turned into the Fed’s “rate hikes.”

After some tense moments (for the mainstream) in France, Germany’s 2s came back to their “senses” in March 2017. What had been -96 bps in “yield” toward the end of February moved to -72 bps just over a month later. Since then, however, yields in Germany and across the world have been falling again, bringing up that unsettled feeling. |

US Dollar / China Yuan 2014-2015(see more posts on USD-CNY, ) |

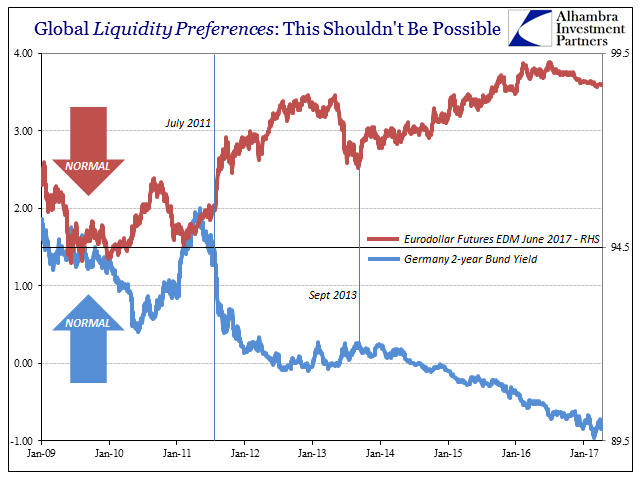

| And so the bond market in all these places suggests to us just how mainstream convention is backward – lower yields are supposed to be because of the “stimulus” of central bank buying when in fact lower yields are instead the market pricing the increasing probability of failure of the buying program “stimulus.” In that way, both are actually on the same side. The market as well as central banks are all reacting to the same thing, with the latter powerless to do anything about it and the former, over time, increasingly aware of that established fact. The “rising dollar” period did more than any other prior time to demonstrate conclusively this is the way it is.

If it was all just Germany or Europe then maybe you could make a sketchy case for ECB idiosyncrasies. As mentioned in my quote above, there is an alarming mirror between eurodollar futures and German 2s that suggested what I describe rather than the “stimulus” myth. |

Global Liquidity Preferences: Germany Bond Yield, Eurodollar Futures Compared |

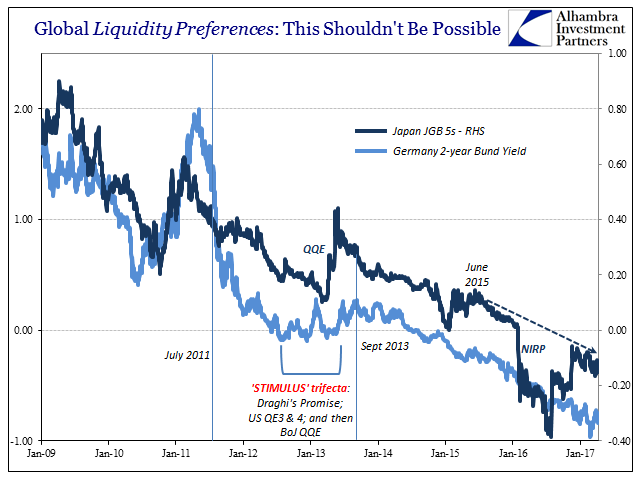

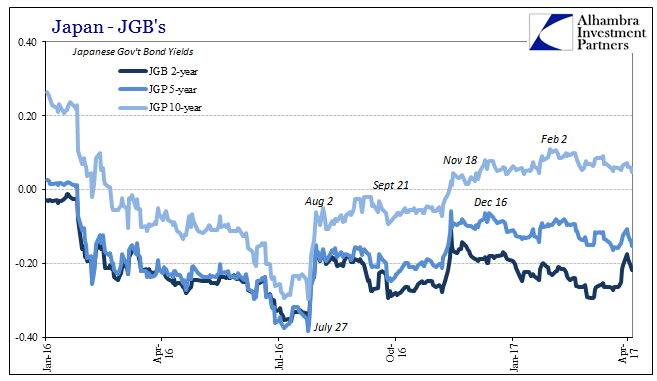

| I can add JGB 5s to the weight of corroboration, too. Accounting for the idiosyncrasies of Japanese banks having to deal with the circus of BoJ policy, the direction for JGB’s is of an entirely too similar direction and even degree.

In the past few months, JGB “yields” have been working backward, too. By mid-December, it began to look as if the 5s might actually turn positive for the first time since NIRP, but instead the JGB market has simply returned to the prior trend; one that dates back to early June 2015 and the first rumblings of the same “global turmoil” clearly impacting Germany’s federal bund market. |

Global Liquidity Preferences: German Bund Yield - Japan Government Bonds Compared(see more posts on Japan Government Bonds (JGB), ) |

Among the motivations for the JGB reversal is the return and persistence of JPY appreciation, which together draws these contradictory indications from BoJ policy that completely fits the description of a circus (subscription required).

The overall result of which has been for Japan a JGB market that begins to look suspiciously suspicious of “reflation.” And why wouldn’t it be? One of the key assumed differences for it was supposed to be central banks getting their act together and not making the same kinds of mistakes as before, if not lucking themselves into something that actually worked as designed and publicly declared. It was none other than Japan (and the “helicopter” rumors) that started this relative surge in optimism to begin with. The JGB market has instead become more of a mess than it was, meaning that the BoJ is still making the same kinds of mistakes if in different places than before. |

Japan Government Bonds 2016-2017(see more posts on Japan Government Bonds (JGB), ) |

Therefore, in Japan, as Germany, it reduces the assumed probability for a positive (economic) outcome, which was already considerably less than in 2013, signaling worldwide that maybe nothing has really changed even if some acronyms were swapped, some QE’s adjusted, and even one central bank, the Fed, becoming increasingly antsy to distance itself from the whole “stimulus” business. Even if you still believe, after all this, that central banks are the powerful instruments they are claimed to be, what would be your response to a world where they threw everything they had at the economic problem and achieved nothing tangible? You might pay a little higher premium than yesterday for liquidity, too.

Tags: $JPY,Bank of Japan,bond market,Bonds,bund yields,Bunds,Central Bank,currencies,depression,economy,Euro,EuroDollar,eurodollar futures,Europe,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,France,Germany,Japan,Japan Government Bonds (JGB),JGB,lost decade,Markets,newsletter,populism,QE,QQE,USD-CNY,Yield Curve