Understanding what is at stake and what it means for markets as the world's largest elections commence.Today, India’s 2019 general elections to determine the next Lok Sabha (the lower house) kick off. India is divided into 543 constituencies, each represented by one member of the Lok Sabha. The party or the coalition that wins a simple majority (272 seats) will form the government. Nearly 900 million voters across the nation will head to election booths to cast their votes over the next five weeks until 19 May. The final results will be counted on 23 May.Current poll results, which tend not to be a highly reliable indicator for a variety of reasons, point to Prime Minister Modi’s BJP as the front runner, but short of obtaining a majority. As things stand, the most likely scenario seems to

Topics:

Team Asset Allocation and Macro Research considers the following as important: elections, India, Macroview

This could be interesting, too:

Marc Chandler writes Continued Backing Up of US Rates Extend the Greenback’s Gains

Marc Chandler writes Consolidation Featured

Marc Chandler writes Double Whammy: US CPI and Federal Reserve

Marc Chandler writes Election Results Lift India But Weigh on Mexico

Understanding what is at stake and what it means for markets as the world's largest elections commence.

Today, India’s 2019 general elections to determine the next Lok Sabha (the lower house) kick off. India is divided into 543 constituencies, each represented by one member of the Lok Sabha. The party or the coalition that wins a simple majority (272 seats) will form the government. Nearly 900 million voters across the nation will head to election booths to cast their votes over the next five weeks until 19 May. The final results will be counted on 23 May.

Current poll results, which tend not to be a highly reliable indicator for a variety of reasons, point to Prime Minister Modi’s BJP as the front runner, but short of obtaining a majority. As things stand, the most likely scenario seems to be that the National Democratic Alliance (BJP and its key allies) will obtain a simple majority of seats, or at least get very close to it so that a BJP-led coalition can form the next government. Under this scenario, one should expect policies to remain largely unchanged, although the BJP (and Modi) may face more checks and balances from its coalition partners. Alternative scenarios are also possible, but of lower probability.

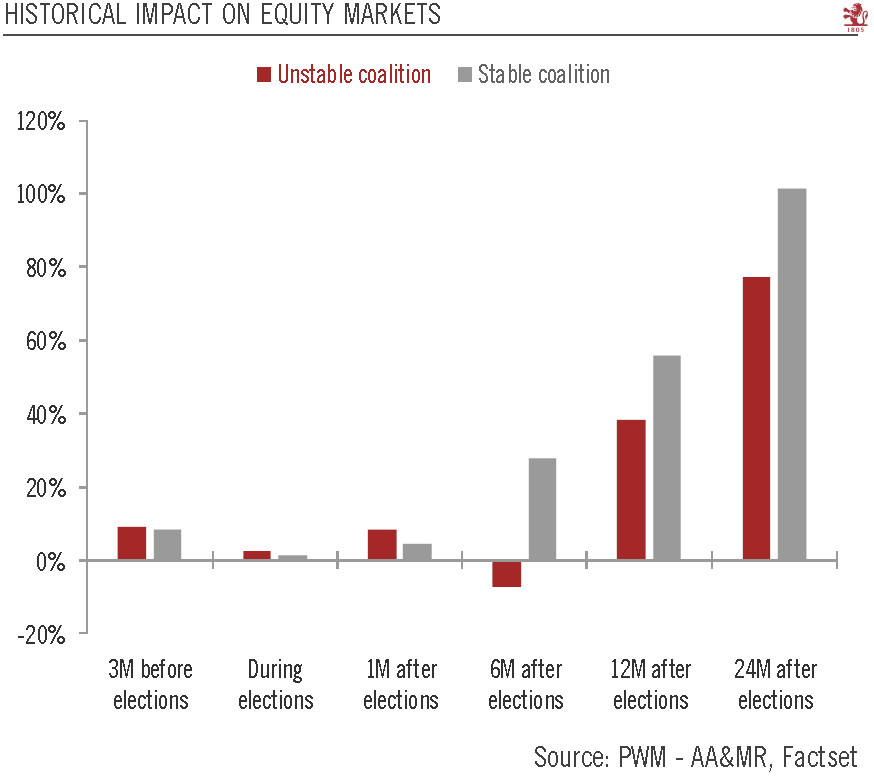

Since 1980, unstable coalitions tend to generate a lower return in Indian equities in the months following election results (both in local currency and dollar terms). Such instability can either materialise quickly, when the winning party tries to form a government, but also over time as dissensions gradually appear within the governing coalition due to the political agenda. General elections in 1989, 1996 and 1998, notably, yielded such unstable coalitions that eventually led to early general elections.

Beyond differences in their political stance and strategy for the upcoming elections, both the BJP and the Congress are likely to pursue the direction of reforms imposed in recent years in order to further modernise the economy. Therefore, although markets are currently hoping for Modi to stay in power – as evidenced by the rally which coincided with the BJP’s improving polls since March – a stable government is likely what would matter most to local equities than which party ends up governing.