People born between 1981 and 1996 are radically changing the patterns of consumption established by their predecessors, in ways that are adversely affecting some industries and favouring companies which take advantage of the increasing spending power of younger consumers.Millennials are a group of people who were born between 1981 and 1996, which makes them between 22 and 37 years old in 2018. They are important for two reasons: there are more than 80 million millennials in the US today, making them a larger population group than the baby boomers born between 1946 and 1964 who number 76 million; and they are entering the prime spending years of their mid-thirties, when they become the largest discretionary spenders with average annual spending growth of 3–4 per cent.The impact on the US

Topics:

Perspectives Pictet considers the following as important: Consumption trends, Future of consumption, In Conversation With, Pictet Report, Pictet Report Autumn 2018

This could be interesting, too:

Perspectives Pictet writes House View, October 2020

Perspectives Pictet writes Weekly View – Reality check

Perspectives Pictet writes Exceptional Swiss hospitality and haute cuisine

Jessica Martin writes On the ground in over 80 countries – neutral, impartial and independent

People born between 1981 and 1996 are radically changing the patterns of consumption established by their predecessors, in ways that are adversely affecting some industries and favouring companies which take advantage of the increasing spending power of younger consumers.

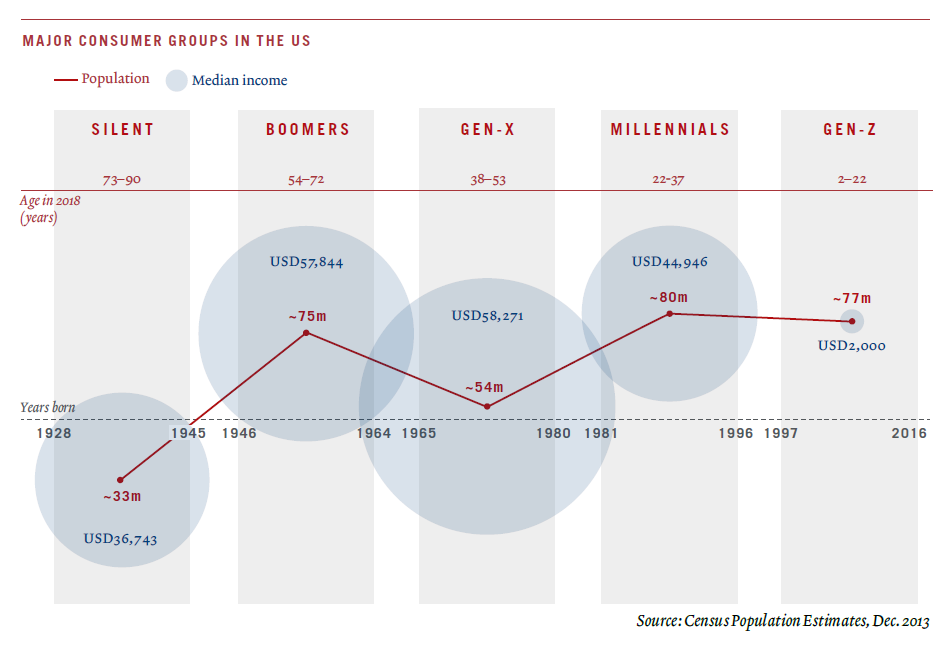

Millennials are a group of people who were born between 1981 and 1996, which makes them between 22 and 37 years old in 2018. They are important for two reasons: there are more than 80 million millennials in the US today, making them a larger population group than the baby boomers born between 1946 and 1964 who number 76 million; and they are entering the prime spending years of their mid-thirties, when they become the largest discretionary spenders with average annual spending growth of 3–4 per cent.

The impact on the US economy will be that millennial spending will grow from USD1.2 trillion to USD2.1 trillion over 15 years. In contrast, the spending of baby boomers is halving as they enter retirement – falling from USD1.5 trillion to USD780 billion. This handover in generational spending is happening right now, and investors need to position themselves to capture this consumer spending growth.

During the millennials’ birth era, the world flattened and globalization exploded. As a result, millennials have had more exposure to the rest of the world and were the most ethnically diverse cohort ever. Their wealthy Generation X parents made them feel valued, secure and hopeful – they are often described as an ‘entitled’ generation – with high expectations of products and services. These self-confident, self-absorbed, always-on technology adopters are shaping the culture of the early 21st century in different ways to previous generations.

Behind this reshaping are the characteristics of millennials. They are liquid, defying categorisation as they change their identity, free from context or social setting – being fully enabled by mobile data.

They are less wealthy than people were in the past, which makes them very price-sensitive for brands and products that are not differentiated from competitors. But while they have less money, they are very value-focused and are willing – thanks to their parents’ finances – to pay for quality or status.

They are also highly educated: 45 per cent have a university degree, which should reap handsome economic rewards for them in the future. And they are very tech savvy, having grown up on the internet and with smartphones. They are well-informed and quick to adopt new technologies. Finally, they are into health and wellness, taking a more active role in physical fitness than keeping to an ideal weight or getting enough sleep.

Certain industries are starting to feel the impact of these distinctive economic and behavioural characteristics. In retail for example, millennials use smartphones to help them when they shop in a store. Four out of five people aged between 18 and 34 in the US own smartphones, four out of five smartphone owners are smartphone shoppers and 84 per cent of them use their phones to help them shop while in a store.

Before, people would go to a shopping mall or department store and be price-takers. Now with the internet, smartphones and social media, millennials can find the best prices anywhere at all times. They also prefer smaller speciality stores like Lululemon and Ulta rather than department stores, because they feel that they offer greater value for money and better service.

They are also a generation of convenience, who like to find something quickly and have it delivered to them fast – which makes Amazon attractive to them. This has been a wake-up call for traditional retailers like department stores which have had to make it possible to order items online and deliver them to the customer’s home within a reasonable time. On the other hand, the value focus is still very powerful for millennials – enough to warrant them going to discount stores such as TJ Maxx in the US which are much cheaper than Amazon.

A second industry which is feeling the millennial impact is food and beverages. Millennials look at ingredient labels a lot and try to buy fresh, organic and natural foods. Volumes of heavily processed foods, canned foods and canned drinks sold in the US are declining, and they are really taboo for millennials. Most of them live in cities, so they are close to supermarkets and able to make more frequent trips to find the foods they want – so the shelf-life of natural products is not an issue.

In this context, one of the trends that has surprised me is that a sector doing really well at a time when millennials are really concerned about the food they eat is chocolate companies. I think that reflects the fact that they are still human: after a full day of eating raw vegetables and grains, they want to spoil themselves!

The tendency of millennials to live in cities has also had consequences for the automobile industry. In previous generations, owning a car was an affirmation of freedom and personal identity, desired at a time when the explosion of suburbia required more commuting and affordable when fuel prices were low. But millennials today don’t care about cars: cities are growing, smartphone mobility provides freedom, and delayed family formation makes it easier to use public transport.

From 2007 to 2011, the number of cars bought in the US by people aged 18–34 fell by 30 per cent. Millennials have developed a preference for walkable lifestyles, while rising fuel prices have made driving more expensive. Internet and mobile technologies such as Uber, Zipcar and Blablacar have made driving less necessary, and possibly less attractive than alternatives. And the cost per kilometre of sharing a car is almost half that of owning a car, which is used around only 5 per cent of the time and spends the rest of the day parked somewhere that may involve paying for a parking slot.

A final concern for millennials is their commitment to environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices when investing. They really want to be responsible investors, and at Pictet Wealth Management we have for some time been integrating ESG and sustainability into our investment process. In the early days, this mainly amounted to exclusion of investments exposed to industries such as tobacco, alcohol or armaments, but it is now turning to broader ESG and sustainability policies. For example, we are increasingly asked about board diversity: millennials want to know how many women are on boards or in senior management.

Millennials are not the end of the generational transformation of consumption patterns. Some 77 million members of Generation Z, also known as centennials, have been born since 1997 – making them as large a cohort as the millennials. They are the most diverse generation, with almost half of them belonging to a minority group. Although Gen-Z does not have a lot of money (yet), they are already becoming a force in consumer spending.

For example, they use their smartphones an average of 15.4 hours per week, more than any other generation. And as attention spans become shorter (down to eight seconds!) companies need to grab it quickly through online ‘snackable’ data – a mixture of text, images and video. Visualisation is important, because centennials share content through social media, and it must embrace their diversity.

The potential for higher returns from companies that position themselves to benefit from the changing consumption patterns of millennials and centennials should make them especially attractive for investors.