In this post, we provide a rough assessment of the reflationary impact of the newly-announced ECB’s measures through a simple framework. Ahead of the December 2015 meeting, we used a simple method based on the ECB’s leaked models in the German press in order to guestimate the impact of QE on inflation, and thus the potential for additional easing based on the ECB’s own forecasts. We use the same framework to assess the potential macro impact of the new measures announced by the ECB last week. Our main argument is that on top of the fresh stimulus coming from a EUR20bn increase in monthly asset purchases (bringing QE total size close to EUR2,000bn by mid-2017), we expect other credit easing measures, including the TLTROs II and the corporate bonds purchase programme (CSPP), to materially improve the transmission of monetary policy. As a result, we use the ‘strong transmission’ QE elasticities in our estimates, adding this macro boost to the anticipated effects of existing measures. We also assume that the QE programme will not be stopped immediately in Q2 2017, but rather slowly tapered within 3 to 6 months. Our findings suggest an extra 0.3% boost to inflation, pushing the staff projection for 2018 HICP inflation to 1.9%, in line with the ECB’s target.

Topics:

Frederik Ducrozet considers the following as important: ECB, Macroview, Monetary Policy, QE, Quantitative Easing

This could be interesting, too:

Marc Chandler writes US Dollar is Offered and China’s Politburo Promises more Monetary and Fiscal Support

Marc Chandler writes US-China Exchange Export Restrictions, Yuan is Sold to New Lows for the Year, while the Greenback Extends Waller’s Inspired Losses

Marc Chandler writes Markets do Cartwheels in Response to Traditional Pick for US Treasury Secretary

Marc Chandler writes FX Becalmed Ahead of the Weekend and Next Week’s Big Events

In this post, we provide a rough assessment of the reflationary impact of the newly-announced ECB’s measures through a simple framework.

Ahead of the December 2015 meeting, we used a simple method based on the ECB’s leaked models in the German press in order to guestimate the impact of QE on inflation, and thus the potential for additional easing based on the ECB’s own forecasts. We use the same framework to assess the potential macro impact of the new measures announced by the ECB last week.

Our main argument is that on top of the fresh stimulus coming from a EUR20bn increase in monthly asset purchases (bringing QE total size close to EUR2,000bn by mid-2017), we expect other credit easing measures, including the TLTROs II and the corporate bonds purchase programme (CSPP), to materially improve the transmission of monetary policy. As a result, we use the ‘strong transmission’ QE elasticities in our estimates, adding this macro boost to the anticipated effects of existing measures. We also assume that the QE programme will not be stopped immediately in Q2 2017, but rather slowly tapered within 3 to 6 months.

Our findings suggest an extra 0.3% boost to inflation, pushing the staff projection for 2018 HICP inflation to 1.9%, in line with the ECB’s target. To be clear, this is not our forecast, but an estimate that would be consistent with the ECB’s own assessment of economic conditions and transmission mechanisms. This estimate, in turn, suggests no immediate need for the ECB to ease policy further, barring another external shock of course.

We will discuss more specifically at a later stage the effects of credit easing measures, especially the new TLTROs II, on bank credit and GDP growth.

As we argued before, no one can realistically expect to fully encapsulate the impact of the ECB’s unconventional measures with just one econometric model, let alone disentangle the lagged effects of those measures operating through different transmission channels. We think it is better to keep it simple, providing rough estimates of the macro impact of the ECB’s QE.

Building on previous analysis[1], we reassess the reflationary impact of the ECB’s measures adding a simple argument: credit easing measures – private QE and TLTROs – will help improve the transmission of the ECB’s monetary stance to a great extent. Actually, there is some evidence that significant progress has been achieved already, including in the ECB’s Bank Lending Survey. This, in turn, argues in favour of higher elasticities of macro variables (GDP growth and HICP inflation) to changes in the ECB’s asset purchases.

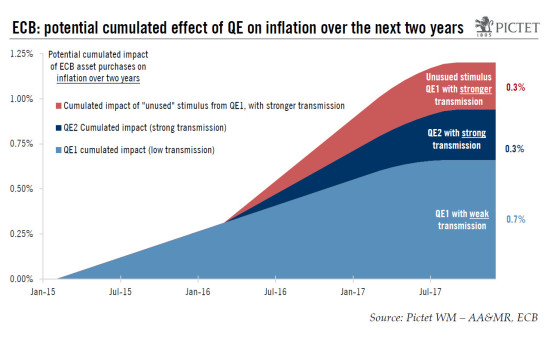

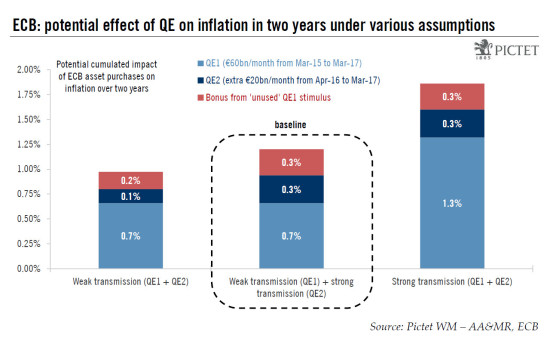

With all those caveats in mind, our reasoning goes as follows: we apply the ‘weak transmission’ elasticity to QE1 (a 0.04 percentage point boost to inflation, over the next two years, for each EUR100bn of asset purchases), i.e. to the EUR60bn monthly purchases between March 2015 and March 2017; we then apply the ‘strong transmission’ elasticity to QE2 (a 0.08 percentage point boost for each EUR100bn), i.e. to the EUR20bn extra purchases between April 2016 and March 2017 amounting to EUR240bn in additional purchases. We assume that asset purchases will not be stopped in April 2017, but rather tapered over six months until end-September 2017, reaching a total of EUR2,000bn by then. Last but not least, we assume that an improved policy transmission from enhanced credit easing measures will help unleash part of the ‘unused’ – or ‘underutilised’ – stimulus from QE1, increasing the elasticity from ‘weak’ to ‘strong’ for those asset purchases conducted between April 2016 and March 2017 (another arbitrary assumption).

Our results can be described as follows:

- The EUR20bn expansion in asset purchases (QE2) can be expected to boost inflation by up to 0.30% by 2018;

- An improved transmission of the ECB’s monetary stance has the potential to strengthen the impact of previous asset purchases (QE1) by another 0.30% by 2018.

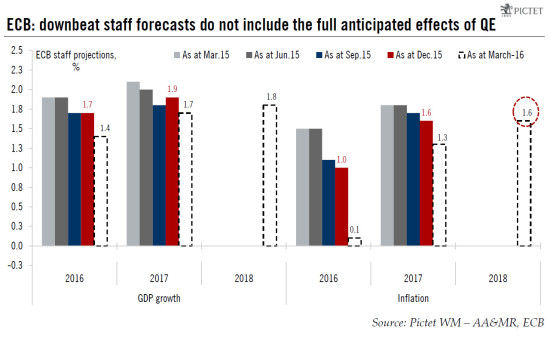

The last assumption we need to make is about the counterfactual situation: what is the benchmark to which we should add the anticipated effects of new ECB measures? Our understanding is that the ECB staff projections from the March meeting did not include the full anticipated effects of the newly-announced policy measures, via portfolio rebalancing, FX or other expectations channels. We have argued that there could be two main reasons for this change in methodology: 1) some of the new measures (TLTRO II and CSPP) are complex and not expected to be implemented before June, meaning that the ECB’s staff may plan to reassess their impact once all details are known and a thorough analysis is conducted; 2) importantly, the ECB may have been willing to set a lower bar in terms of economic forecasts, creating the conditions for macro data to surprise to the upside in coming months, thereby reducing the need for additional action.

Therefore, we think it is appropriate to use the March staff forecasts as the counterfactual situation (without QE2, TLTRO II and CSPP). Our estimates suggest that QE expansion should result in the ECB staff projection for 2018 HICP inflation being revised upwards from 1.6% to around 1.9%, in line with the target. This figure happens to be in line with (unconfirmed) press reports suggesting that the long-term inflation staff projection could be increased by 0.20-0.30%. Another approach leading to a similar conclusion would be to add the cumulated boost of both QE1 and QE2 to the underlying inflation rates, currently at just below 1% – the projected rate of inflation would end up close to 2% as well in that case.

The improved transmission of monetary policy may point to upside risks to those forecasts, to the tune of 0.30% by 2018. That said, in spite of our positive assessment of the ECB’s easing package, there is a strong case for a cautious approach to the above calculations. In particular, the ECB’s models were said to largely rely on the FX channel, with the bulk of QE’s reflationary impact expected to come through further depreciation in the trade-weighted EUR. While this may still happen via the portfolio rebalancing effect, the initial reaction of the rates and FX markets should act as a reminder of diminishing marginal return of central banks’ announcements.

Any adverse shock to activity may also reduce the effects of QE on inflation. We will discuss more specifically at a later stage the effects of credit easing measures, especially the new TLTROs II, on bank credit and GDP growth.

[1] See our special focus “ECB QE2: when, how, how much?” in October 2015 Perspectives for details.