A study from The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco claims that most of the price inflation that plagued the US economy over the past few years was due to global supply chain disruptions, due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Is this a valid study, or an attempt by the Fed to evade responsibility for our recent economic troubles?There are several problems with this study. First, this study aims at establishing a correlation between supply chain disruptions and “above trend” price-inflation rates. The two-percent trend used in this study is actually just the minimum rate of inflation that the Fed has targeted deliberately since 1996. It is disingenuous for the Fed to treat the two-percent minimum inflation rate that it chose as a “trend,” for which it lacks

Topics:

D.W. MacKenzie considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

A study from The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco claims that most of the price inflation that plagued the US economy over the past few years was due to global supply chain disruptions, due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Is this a valid study, or an attempt by the Fed to evade responsibility for our recent economic troubles?

There are several problems with this study. First, this study aims at establishing a correlation between supply chain disruptions and “above trend” price-inflation rates. The two-percent trend used in this study is actually just the minimum rate of inflation that the Fed has targeted deliberately since 1996. It is disingenuous for the Fed to treat the two-percent minimum inflation rate that it chose as a “trend,” for which it lacks responsibility.

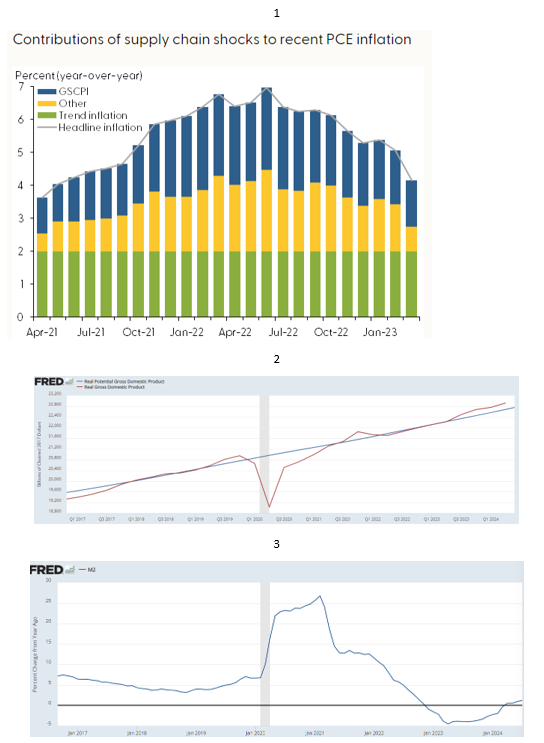

Fed officials could have chosen a one-percent minimum, or better still, zero-percent price stability. They chose to maintain at least two-percent price inflation, indefinitely. Price inflation that this study identifies as neither trend nor due to supply chain restrictions, is listed as “other” (see chart 1). Attribute “trend” and “other” price inflation to Fed policy, and the Fed is responsible for most of recent price inflation in the USA, even if this study is otherwise correct.

This study identifies three alleged channels through which supply chain disruptions may have raised the rate of price inflation. First, they claim that effects of the Covid shock, as measured in Global Supply Chain Pressure Index, correlate with expected price inflation, as measured in the Philadelphia Fed’s Survey of Professional Forecasters. Is it really surprising that the price inflation forecasts of professional forecasters correspond to actual price-inflation rates? How could these people keep their jobs as forecasters without making accurate forecasts? Correlation doesn’t imply causation. Furthermore, the idea that price-inflation expectations cause price inflation begs the question as to how people can actually carry out total transactions at higher prices without increases in the total money supply.

Second, Covid supply chain disruption may have raised import prices. The authors of this study admit that import prices are a trivial part of the US cost of living.

Third, this study claims that global supply chain disruptions during the COVID crisis raised prices of “intermediate inputs” (materials, unfinished goods, labor, and capital). Higher input prices then get passed on to consumers. Price-inflation derives from too much money chasing after too few goods. This study is focusing exclusively on there being too few goods during the C-19 crisis. Supply chain disruptions are only one possible cause of there being too few goods, and the effects of any supply restriction must be compared to the availability of money in circulation—as determined by Fed policy.

The authors of the study insist that supply-chain restrictions caused increases in price-inflation rates that began in early 2021. The overall economic situation in the first quarter of 2021 was similar to the economic situation in the third quarter of 2017—actual GDP was approaching potential GDP in both cases (see chart two). However, the specific problem in 2017 was tight labor supply, not supply chain disruptions. Labor supply tightened from 2017 to 2021 for several reasons. First, baby boomer retirement. Second, elevated overdose suicide and rates. Third, Covid fatalities. Fourth, President Trump’s immigration policies. The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco published another study, which identified Trump’s immigration policies as a quantitatively significant and unexpected source of tight labor supply, a true supply shock.

We have two recent examples of tight supply conditions, one involving labor in 2017, the other involving global supply chains 2021. Price inflation was problematic in the latter, not the former. Why? The Fed slowed the rate of M2 money supply growth in 2017 and 2018 (see chart three). The Fed greatly accelerated the rate of M2 money supply growth in 2020 and 2021.

Did supply chains disruptions really matter in 2021? Tight labor supply created many job vacancies at that time. That being the case, an earlier untangling of supply chains likely would have had little effect, the economy was approaching full capacity in 2021. The main point though is that recent price inflation came in the wake of a huge M2 money supply increase—and this is no coincidence.

The Federal Reserve greatly expanded the money supply a few years ago, and recovery from the Covid shutdown speeded up the circulation of this money in the economy. An increase in money velocity would have happened during the reopening in any case. The Fed did not need to increase the money supply in response to the Covid-19 crisis. Fed policy caused the recent wave of price inflation in the US, and did so unnecessarily.

Tags: Featured,newsletter