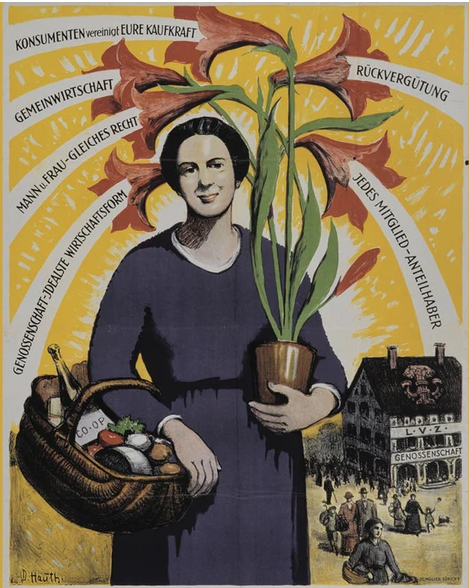

Blossoming cooperative ideas: a common economy, consumer protection and equality of the sexes. Dora Hauth-Trachsler/Schweizersiches Sozialarchiv The word “cooperative” is everywhere in Swiss daily life. What’s often forgotten is that cooperatives were once at the forefront of a worldwide movement that advocated for consumer rights, affordable rents – and world peace. In his opening speech at the tenth international congress of the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) in Basel in 1921, the president of the federation of Swiss consumer associations, Rudolf Kündig, struggled for words. “We were too powerless,” he said. “The belief that we as cooperative members could stop a war lies in ruins.” The previous time the alliance had met, Russia was still ruled by a

Topics:

Swissinfo considers the following as important: 3.) Swissinfo Business and Economy, 3) Swiss Markets and News, Culture, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Blossoming cooperative ideas: a common economy, consumer protection and equality of the sexes. Dora Hauth-Trachsler/Schweizersiches Sozialarchiv

The word “cooperative” is everywhere in Swiss daily life. What’s often forgotten is that cooperatives were once at the forefront of a worldwide movement that advocated for consumer rights, affordable rents – and world peace.

In his opening speech at the tenth international congress of the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) in Basel in 1921, the president of the federation of Swiss consumer associations, Rudolf Kündig, struggled for words.

“We were too powerless,” he said. “The belief that we as cooperative members could stop a war lies in ruins.”

The previous time the alliance had met, Russia was still ruled by a tsar and Germany by an emperor. The cooperative world now eagerly awaited the first congress since the end of the war.

For decades the ICA had taken a clear stance on the subject of conflict: it saw itself as nothing less than a movement for world peace. The alliance often emphasised that its mission was economic and not political. But its economic ideas were so all-encompassing that it believed cooperatives had a peace-building effect.

Listening attentively to Kündig speaking in Basel were representatives from places such as Argentina, Ukraine, Latvia and the United States. The British movement, the birthplace of modern cooperatives in the 19th century, sent a delegation of 100 people. Guests from the Soviet Union were less fortunate – various Western European states refused to give them visas.

‘Conciliatory bridge’

The Basel congress was attended not only by cooperative supporters: the Swiss president was present, as were four representatives from cantonal governments. Also taking part was the young League of Nations, whose Japanese under-secretary general Inazo Nitobe gave a speech expressing wide support for the gathering. The League of Nations viewed the congress with “great interest”, he said, explaining that it was more amenable to the cooperative movement than many other institutions.

“It has become obvious to me that the League of Nations and the cooperatives share the same goals,” Nitobe said. The cooperative movement was a “conciliatory bridge” between the “purely capitalist economic system and that of the adversaries, the communists and socialists”. Correspondingly, the League of Nations recognised “the work of cooperative members in reconciling between peoples”.

According to British historian Rita Rhodes, during the First World War the cooperatives had managed to keep their distance from warring parties.

“The International Cooperative Alliance viewed the First World War as a capitalist and imperialist conflict,” says the elderly Rhodes, the last official historian of the International Cooperative Alliance.

As an international movement, it had been able to continue communications without interruption, for example circulating its Monthly Bulletin internationally despite censorship and paper shortages. Written in London, during the war the texts travelled via the Netherlands to continental Europe, where cooperative members translated the English originals into German. Meanwhile, the Swiss cooperative movement would contribute the French translations. “That way the international movement always had a connecting element,” Rhodes says.

However, the national cooperatives couldn’t escape the war: their members were conscripted for military service, and cooperative possessions, horses for example, were employed for warfare. Some governments suspended the regulations allowing cooperatives to operate economically.

For Rhodes, the 1921 congress was like a “reconciliation process”. “The war created tensions and ruptures between the national movements. Basel enabled personal exchanges to occur again and a mutual understanding of how the war had damaged the individual movements.”

The most controversial debate in Basel revolved around how to deal with the Soviet Union. Were the sister organisations there really allowed to operate freely, as the Soviet representatives who had managed to travel from London claimed? Or were they under the totalitarian control of the state, as the French delegates argued? Ultimately a clear majority voted for the continued membership of the Soviet Union in the international movement.

Preventing a Second World War

What proved less contentious was the Basel declaration by the representatives opposing all wars. This commitment to a “cooperative Europe” was drafted and presented by the French economist and cooperative ideologist Charles Gide. It stated that a completely cooperative economy and a society based on the same “moral principles” would eliminate the “essential causes of wars”. It called on cooperative members in the individual countries to agitate for minimal military spending and the “complete disarmament of all states”.

The Basel declaration rounded off with a commitment that the “cooperative members of all countries” would stop any new war with a “joint action” and “without fear of patriotic prejudices”, and so compel an end to hostilities. If “the madness of humanity were to unleash a new war”, this action by the cooperative movement would force a resolution of the conflict via a “ruling by a court of arbitration”. Precisely who would initiate this court of arbitration, and how it would enforce its judgement, was left open. There were no international courts at the time.

Looking back, the cooperative members’ belief in their own power and in the clout of international organisations appears to have been immense. But, as we know, things took a different turn. Already in the 1920s, the Fascist dictatorship in Italy smashed the local cooperative movement. At the same time, the ICA was forced to struggle with a string of sharply worded motions from the Soviet cooperative functionaries, aimed at derailing the cooperative international’s pacifist course. The ICA assembled in Ghent, Stockholm, Vienna and, in June 1933, for an extraordinary conference in Basel for a second time.

On the eve of the conference, the International Cooperative Alliance received a telegram telling them that the representatives from Germany would be two Nazi functionaries. The National Socialists had taken control of the cooperative movement in May 1933 and absorbed them into their totalitarian system. The Nazis were allowed to participate, but they stayed for less than a day. One of the Nazi delegates took the microphone as the first speaker and compared Hitler’s seizure of power with the French Revolution, which caused an uproar. The Nazis left. It was the ICA that tried to maintain contact.

‘Positive peace’

While the international cooperative movement was based on democratic, pacifist and progressive ideals, some of the branches harboured reactionary tendencies. The Austrian Fascist dictator Engelbert Dollfuss – who after his seizure of power had leading members of the Austrian cooperative movement arrested – was himself an enthusiastic member of an agricultural cooperative.

Moreover, the cooperative worldview, according to which wealthy individuals were in business only for their own interests and thus prevented prosperity for all, struck a chord with strands of anti-Semitic thinking.

The ICA renewed their peace declaration in 1939 and today remains committed to “positive peace”, as last enshrined at their general assembly in Rwanda. “Conflicts are caused by unsatisfied human needs,” said the declaration of 2019, whereas the mission of the cooperatives was to fulfil them.

Globally and in Switzerland, cooperatives still play an important role in the economic sphere. According to the ICA’s World Cooperative Monitor, almost 12% of the world’s population are today members of a cooperative.

However, very few cooperatives are still active in the International Cooperative Alliance. The Association of Swiss Consumer Societies , the organisers of the 1921 congress, evolved to become what is currently the largest supermarket chain in the country, Coop. At the end of the 20th century Coop left the international cooperative movement. The reason, in response to an enquiry, was an “organisational reorientation”.

Translated from German by Thomas Skelton-Robinson/ts

Tags: Culture,Featured,newsletter