Since superfluous demand was the core driver of most consumer spending, and that demand is in free-fall, what’s the upside of re-opening? The mainstream view assumes everyone will be gripped by an absolutely rabid desire to return to their pre-pandemic frenzy of borrowing and spending and consuming, the more the better. While the urge to believe the Titanic scraping the iceberg will have no consequence and the collision was nothing but a spot of bother is compelling (so party on!), many people will reassess their pre-pandemic lives and ask: do I really want to go back to circling the pavement in a dead end? Being away from the crazy-busy churn invites reassessment, especially for small business owners who are facing the near-certainty of uncertain sales and

Topics:

Charles Hugh Smith considers the following as important: 5.) Charles Hugh Smith, 5) Global Macro, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Since superfluous demand was the core driver of most consumer spending, and that demand is in free-fall, what’s the upside of re-opening?

Since superfluous demand was the core driver of most consumer spending, and that demand is in free-fall, what’s the upside of re-opening?

The mainstream view assumes everyone will be gripped by an absolutely rabid desire to return to their pre-pandemic frenzy of borrowing and spending and consuming, the more the better. While the urge to believe the Titanic scraping the iceberg will have no consequence and the collision was nothing but a spot of bother is compelling (so party on!), many people will reassess their pre-pandemic lives and ask: do I really want to go back to circling the pavement in a dead end?

Being away from the crazy-busy churn invites reassessment, especially for small business owners who are facing the near-certainty of uncertain sales and still-high fixed costs.

When we’re embedded in the crazy-busy churn, we’re only trying to get through the day. Once we’re removed from the pressure-cooker of running the business, we start wondering: is this craziness what I want to spend the rest of my life pursuing? For what gain? Do I really love my business and my customers/clients, or am I just telling myself that I love my business and my customers/clients as duct tape to keep the whole contraption from flying apart?

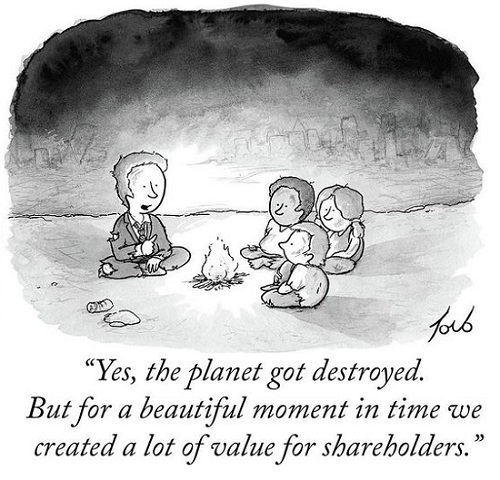

Then there’s the question of Superfluous Demand, a topic Max Keiser and Stacy Herbert and I discussed in their recent Double Down podcast. Superfluous demand is demand that’s a manifestation not of what we might call authentic or organic demand for essentials but demand driven by cheap credit and the consumerist mania to fill the insatiable black hole of insecurity inside every debt-serf to raise their publicly posted social status with an endless stream of aspirational goods and services that shout “Look at me! I have the same things and experiences the top 5% have!”

But sadly, no amount of aspirational goods and services will fill the insecurity or create an authentic positive social role, or express an authentic selfhood that exists outside of the consumerist definition of “self” as nothing more than a consuming machine.

Every business owner and manager has to anticipate a decline in superfluous demand as incomes decline and credit tightens, and households and enterprises recalibrate their exposure to risks of further downside and forego spending in favor of rebuilding a cash reserve. How severe the drop in demand will be correlates with how much of their pre-pandemic sales were manifestations of superfluous demand.

Entertainment, travel and a vast array of consumables were virtually all superfluous, so the decline in superfluous demand will be consequential to virtually every business.

But humans are not just consuming machines generating superfluous demand with credit. Humans have to create the goods and services, and that is an intrinsically risky process. Decisions have consequences, and those consequences weigh heavily on those who are accountable: managers, executives and especially owners, who must cover expenses with their own personal cash if the enterprise’s expenses exceed its net income.

Only owners and previous owners of small businesses know what this potential for personal loss and bankruptcy feel like. Very few of the punditry and corporate media commentators have personal experience in running a business, and especially one on the knife edge between covering expenses and losing money. To all these media commentators, “small business” is an abstraction.

Employees also have no idea what it’s like to be responsible for losses and accountable for decisions that may make or break the enterprise.

Which brings us to the asymmetrical impacts of owners, managers and essential workers in the economy, which is effectively a complex network of critical nodes that all the millions of network participants depend on. Examples include oil refineries, nuclear power plants and slaughterhouses.

The fewer the number of these essential nodes, the more consequential the impact when one or more go offline. Put simply: not all nodes are equal in their impact.

This dynamic is also present in human capital: if a small business has 10 employees, the business will survive the loss of an employee, but it won’t survive the loss of the owner. A region can survive 500 white collar workers not showing up for work, but if 500 slaughterhouse workers don’t show up for work, meat production in the region falls to near-zero.

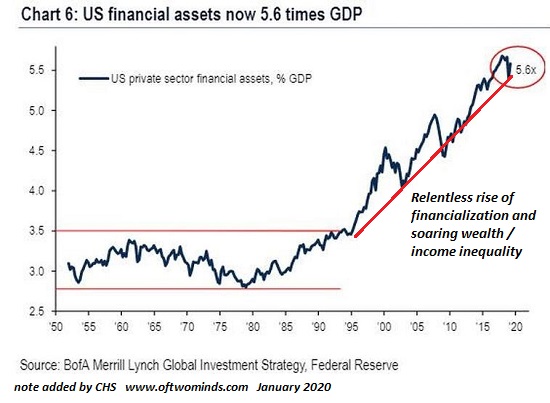

Blinded by their absence of real-world experience, the financial punditry devote their attention to the trillion-dollar Big Tech behemoths, as if they dominate the economy because they’re so incredibly overvalued by Wall Street.

But in the real world, Big Tech’s share of the work force is essentially signal noise. A tiny sliver of the 150 million people with earned income in the U.S. toil for a Big Tech company.

Who really matters in terms of employment and earned income are small business owners, not the Big Tech monopolies.

Which brings us back to the owner who’s wondering if they want to return to the heavy burdens and crazy-busy churn of a business that may well lose money or flounder for years. What’s the pay-off for working extra hours because you can’t afford to hire back all your previous staff? What’s the payoff as rents, healthcare, fees, taxes and the cost of goods all increase while customers balk at any increase in your own prices? Is struggling to survive really what I want to spend the rest of my life doing? And for what? To slowly go bankrupt?

Small business is not a financial abstraction. It is real people who were often burned out even before the pandemic and who are now wondering if it’s wiser to bail out now and close the doors rather than endure a slow side into bankruptcy and exhaustion.

Since superfluous demand was the core driver of most consumer spending, and that demand is in free-fall, what’s the upside of re-opening? Isn’t it more prudent to close up now and preserve whatever capital and health one still has, and pick a way of life that doesn’t require meeting payroll, paying outrageous rents and being liable for calamities that are outside of your control?

Can we be honest, and note that for many owners and managers, their pre-pandemic life was nothing more than a crazy-busy dead end? Why continue the struggle now with even heavier burdens and greater risks, and for what gain?

I’ll tell you what: if “small business” is so great and profitable, then how about you go plunk down thousands of dollars for rent, healthcare, payroll for employees, tax payments, insurance, fees, and on and on, and then take your chances that superfluous demand hasn’t dried up and blown away.

Tags: Featured,newsletter