Regardless of what happens with vaccines and Covid-19, debt and energy–inextricably bound as debt funds consumption– will destabilize the global economy in a self-reinforcing feedback. Back in the early days of the oil industry (1880s and 1890s), the product that the industry could sell at a profit was kerosene for lighting and heating. Since there was no automobile industry yet, gasoline was a waste product that was dumped into streams. Why couldn’t the refiners produce only kerosene? Why did they end up with “worthless” gasoline? The answer is a barrel of oil produces a variety of products. While there is some “wiggle room” to produce more diesel and less gasoline, etc., it isn’t possible to turn a barrel of oil into only one product. John D. Rockefeller became

Topics:

Charles Hugh Smith considers the following as important: 5.) Charles Hugh Smith, 5) Global Macro, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Regardless of what happens with vaccines and Covid-19, debt and energy–inextricably bound as debt funds consumption– will destabilize the global economy in a self-reinforcing feedback.

Back in the early days of the oil industry (1880s and 1890s), the product that the industry could sell at a profit was kerosene for lighting and heating. Since there was no automobile industry yet, gasoline was a waste product that was dumped into streams.

Why couldn’t the refiners produce only kerosene? Why did they end up with “worthless” gasoline?

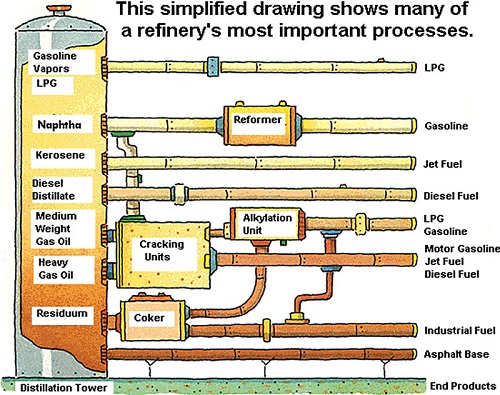

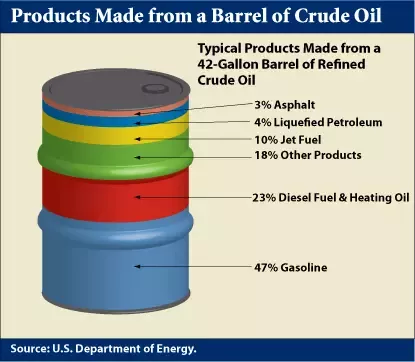

The answer is a barrel of oil produces a variety of products. While there is some “wiggle room” to produce more diesel and less gasoline, etc., it isn’t possible to turn a barrel of oil into only one product.

John D. Rockefeller became very wealthy by cornering much of the oil market in the 19th century. But he didn’t become fabulously wealthy until the 20th century, when the rise of automobiles created a market for all the “waste” gasoline.

Rockefeller became super-wealthy when all the products of each barrel of oil could be sold at a premium rather than just a portion of the products.

This reality has been forgotten: the price that can be fetched for a barrel of oil depends on the demand for all the products, not just a few of the products.

Those demanding an all-electric auto-truck fleet as a “green” alternative will re-create the dilemma of what to do with the “waste” gasoline. The world will still want fuel for all those container ships bringing all the goodies of a consumerist society, all those cruise ships visiting ports of call, jet fuel for all those exotic vacations enabled by 550 mile-per-hour aircraft, and oil-based lubricants, plastics and petro-chemicals, and so oil will still be pumped and refined, and almost half of it will be gasoline.

We can either use it or throw it away but we can’t magically turn a barrel of oil into only one product.

This is a topic worthy of your understanding, so grab a vat of your favorite beverage and turn off all distractions.

Longtime readers know I’ve focused on energy-oil markets for 15 years. Despite ups and downs in price, the oil market has been remarkably stable.

This stability is about to transition to chronic instability: wild swings in price, shortages, and social chaos in both producing and consumer nations.

Let’s start with the most basic dynamics in the cost of producing oil, refining it and selling the products at a profit.

1. As a general rule, a barrel of oil (42 gallons, 196 liters) yields a range of heavier and lighter products.

The price the producers can charge for each product–gasoline, diesel fuel, heating oil, jet fuel, propane, etc.– depends on demand for each product.

If the price for one product falls drastically, the oil producer can’t increase the price of some other product to compensate for the loss of income unless demand for the other products will support higher prices.

Consider the huge decline in demand for jet fuel as a result of global air travel dropping in the pandemic. Oil producers can’t just raise the price of gasoline to compensate for the drop in the price of jet fuel.

If gasoline demand continues declining (due to fewer commutes, etc.) then producers can’t charge more for diesel to make up the drop in the price of gasoline.

In other words, there has to be strong demand for all the products in a barrel of oil for producers to get enough money to extract, refine and transport the products globally.

Unlike the old days when producers could afford to throw away some petroleum products because their costs of extraction and refining were so low, now producers need more than $45/barrel just to break even.

This is what I’m calling Oil Paradox #1: if demand for any of the primary products is weak, producers can’t afford to continue extracting and refining oil, even if there is strong demand for some products.

2. Transportation is the primary use of oil: 68% of all petroleum products are consumed by transport, 26% by industrial and 6% residential/commercial. (These are U.S. statistics, but the global demand is roughly the same.)

If demand for gasoline, diesel and jet fuel remains weak, the value of each barrel of oil will remain below break-even, even if the industrial need for some products (lubricants, etc.) is strong because these industrial products are essential to the world’s industrial economy.

3. Much of the consumption of the past 20 years was funded by debt, which is now $277 trillion globally and accelerating. Humanity has borrowed and spent trillions on consumption, and what remains is the interest due on the debt.

This interest constrains future borrowing. The “solution” to interest is inflation, which devalues the interest due. But it also devalues the purchasing power of the currencies being inflated, and so everyone’s money buys fewer goods and services.

This is the Debt-Inflation Paradox: the more interest you owe, the greater your need to inflate away the burden of interest. But inflation destroys the purchasing power of money, impoverishing everyone who needs the money to live.

|

There is no way out of this paradox: either the global economy defaults on its debts, destroying trillions in phantom wealth, or its currencies lose value, impoverishing everyone. Since so much consumption is funded by debt, any reduction in borrowing, no matter how modest, will destroy demand for petroleum, triggering the Oil Paradox (producers can’t charge enough to justify pumping and refining oil). 4. The pandemic has accelerated consumption trends that reduce demand for fuels. Remote work is here to stay, regardless of what you may read. Corporations can no longer afford to staff centralized offices in costly cities. Making everyone commute to offices is no longer financially viable. Corporate travel is also no longer financially viable. As profit margins fall, the luxury of jetting to physical meetings is no longer justifiable except for senior management– a few dozen people, not hundreds or thousands. Tourism thrived in an economy of easy, low-cost credit and secure incomes. Lenders can no longer afford to lend to those with poor credit–notice how credit card limits have been drastically reduced–and incomes are no longer secure. If the pandemic were the only issue, it would be possible to see a return to 2019-level consumption. But unsustainable debt loads will only get more unsustainable, so much of the consumption that was funded by debt will go away and not come back: the interest on all the existing debt remains to be paid, one way or another. This decline in consumption has lowered the price of oil far below break-even for most producers. As the article below explains, there are two break-even prices for petroleum: one to get it out of the ground, refine it and deliver it to market, and the second for the social costs the oil pays for. This is the famous Oil Curse: nations with oil reserves end up depending on selling oil for virtually all their revenues because it doesn’t make sense to invest in less reliable, less profitable sectors. |

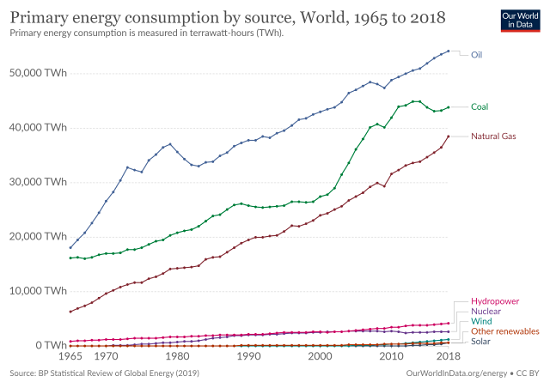

Primary energy consumption by source, 1965-2018 |

| As a result, Saudi Arabia can pump the oil for $45/barrel, but it needs a price of $85/barrel to pay all the social welfare costs it has promised its people.

If you glance at the charts in this article, you’ll see the full break-even price of oil for OPEC nations is extremely high. Breakeven crude oil prices are one metric of the economic constraints This generates Oil Paradox #2: low demand/low prices for oil may be financially viable in terms of extracting the oil, but the societies that depend on vast oil revenues will unravel if oil prices stay low, and that will disrupt production. Roughly half of U.S. petroleum production is from tight shale and other unconventional oil sources. Many of these wells are no longer profitable and will be shut down once the producers’ credit lines dry up. (This is already happening, triggering mass bankruptcies in the fracking industry). The oil producing nations are basically surviving on $40/barrel oil by borrowing against future revenues. This is a dangerous game because if oil prices remain low their credit lines will eventually be withdrawn. The oil producers need supply to fall drastically enough to raise prices back to the $80/barrel or higher level. But nobody can afford to cut their own production enough to reduce global supply enough to matter. This introduces Oil Paradox #3: should petroleum producers succeed to slashing supply so oil goes to $85/barrel, the higher cost will push the fragile consuming nations into recession or depression, which will slash demand even more, which will require even deeper production cuts to maintain prices. If we put all these paradoxes together, we see that oil markets are now intrinsically unstable and cannot return to stability because the mix of high break-even prices, declining demand and the end of debt-funded consumption cannot be resolved: high prices crush demand, low prices crush producers, and debt is crushing both consumers and producers. Much hope is being placed on so-called renewable energy, most of which is not renewable but replaceable, as I’ve learned from Nate Hagens. A forest is renewable, a solar panel or windmill must be replaced every 20 years at enormous expense. |

|

| Right now all alternative energy sources–wind, solar, etc.– generate no more than 4% of global energy consumption. (see chart below) Despite hundreds of billions of dollars invested, all the alternative energy sources are a tiny fraction of global consumption, and their supposed fantastic rates of growth is revealed on this chart as inconsequential: all this new energy doesn’t replace a single drop of oil, it simply fuels additional consumption.

It will take a monumental investment and many years to get this to 10%. The reality is the vast majority of the global economy still depends entirely on petroleum for transport and industrial essentials such as lubricants. How (Not) to Run a Modern Society on Solar and Wind Power Alone Petroleum is now an unstable system and for all the reasons outlined above it cannot be restored to stability: just as time is a one-way arrow, so is the loss of stability. What can we expect? Unstable systems are prone to wild swings to extremes and unpredictable collapses. So we may see collapses in the price of oil as we saw in March, and then rapid ascents in price above $100/barrel, which then crash once demand declines. This unpredictability complicates projections and generates uncertainty. This is the final paradox (#4): the unpredictability of oil markets is itself a destabilizing force. Decisions on future production and consumption cannot be long-term, and this constrains investment in future production. Regardless of what happens with vaccines and Covid-19, debt and energy–inextricably bound as debt funds consumption– will destabilize the global economy in a self-reinforcing feedback. |

Tags: Featured,newsletter