The US personal savings rate jumped to 33 percent in April from 12.7 percent in March and 8 percent in April last year. An increase in savings is regarded by popular economics as less expenditure on consumption. Since consumption expenditure is considered as the main driving force of the economy, obviously a rebound in savings, which implies less consumption, cannot be good for economic activity, so it is held. Saving and wealth—what is the relation? To maintain their life and well-being, individuals require access to consumer goods. An increase in various consumer goods permits an increase in individuals’ living standards. What allows an increase in the production of consumer goods is the maintenance and the enhancement of the infrastructure of an economy. With

Topics:

Frank Shostak considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

The US personal savings rate jumped to 33 percent in April from 12.7 percent in March and 8 percent in April last year. An increase in savings is regarded by popular economics as less expenditure on consumption. Since consumption expenditure is considered as the main driving force of the economy, obviously a rebound in savings, which implies less consumption, cannot be good for economic activity, so it is held. Saving and wealth—what is the relation?

To maintain their life and well-being, individuals require access to consumer goods. An increase in various consumer goods permits an increase in individuals’ living standards. What allows an increase in the production of consumer goods is the maintenance and the enhancement of the infrastructure of an economy.

With better infrastructure, a greater quantity and better quality of consumer goods could be generated and more real wealth can be produced.

The enhancement and the maintenance of the infrastructure becomes possible because of the availability of final consumer goods that sustain the various individuals who are busy expanding and maintaining the infrastructure. It is the producers of final consumer goods who pay the various individuals engaged in maintenaning and enhancing the infrastructure. The producers of final consumer goods pay these individuals (i.e., the intermediary producers) out of the saved or unconsumed production of final consumer goods.

Note that when a producer of final consumer goods decides to save more, i.e., to consume less, the fall in his consumption is offset by the increase in the consumption of individuals who are engaged in the intermediary stages of production. This means that overall consumption is not declining because of an increase in saving—as popular thinking has it.

What keeps the flow of economic activity going is the fact that the producers of final consumer goods—the wealth generators—invest part of their wealth in the expansion and maintenance of the production structure. It is this that permits the increase in the production of consumer goods, which in turn makes it possible to increase the consumption of these goods. Out of a greater production of wealth more can be now consumed. So, the motor of the economy is actually not consumption but rather savings.

Since savings enable the production of capital goods, savings are obviously at the heart of the economic growth that raises people’s living standards.

Note that people do not want various means as such, but rather want final consumer goods. In order to sustain themselves people require access to consumer goods. Only once there has been a sufficient increase in the pool of consumer goods can people aim at enhancing their well-being by seeking other things such as entertainment- and service-related products such as medical treatment.

Saved goods support all the stages of production, from the producers of final consumer goods down to the producers of raw materials, services, and all other intermediate stages.

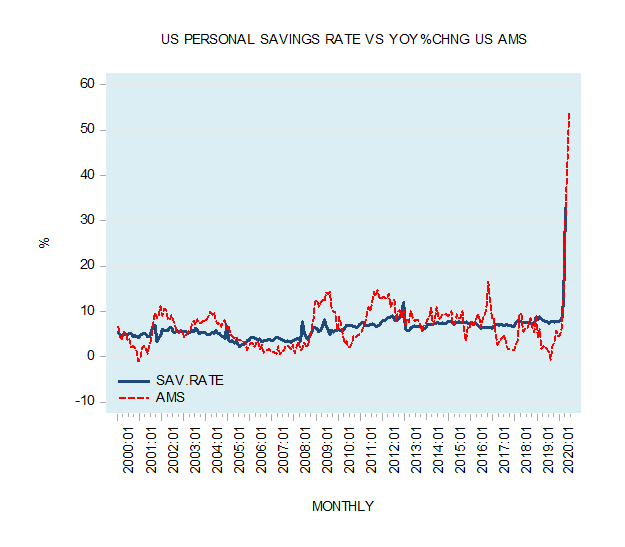

Government Data on SavingIn the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA), the saving rate is established as the ratio of personal saving to disposable income. Disposable income is defined as the summation of all personal money income less tax and nontax money payments to the government. Personal income includes wages and salaries, transfer payments, income from interest and dividends, and rental income. Once we deduct personal monetary outlays from disposable money income, we get the personal saving. The NIPA framework is based on the Keynesian view that spending by one individual becomes part of the earnings of another individual. Each payment transaction has two aspects—the spending of the purchaser is the income of the seller. From this it follows that spending = income. So if people maintain their spending, this keeps overall income going—hence why consumer spending is the motor of the economy. Observe that the total amount of money spent is driven by the increase in the supply of money. Consequently, the more money that is created out of “thin air,” the more of it will be spent and therefore the greater the NIPA’s national income is going to be. In the graph we see that the year-over-year change in the money supply tracks with the savings rate: It shouldn’t be surprising that the so-called personal savings rate closely resembles the momentum of money supply. In this way of thinking there is no need to worry about savings, as the central bank can always boost them. But contrary to the NIPA framework, increases in the money supply in fact lead to the destruction of savings. Here’s how it works. |

US Personal Savings Rate vs YoY % CHNG US AMS |

How an Increase in Money Supply Destroys Savings

In the real world, one has to become a producer before one can demand goods and services. It is necessary to produce some useful goods that can be exchanged for other goods.

For instance, when a baker produces bread, not everything he produces is for his own consumption. In fact, most of the bread he produces is exchanged for the goods and services of other producers, implying that through the production of bread, the baker generates an effective demand for other goods. In this sense, his demand is fully backed by the bread that he has produced.

When money is printed—that is, created “out of thin air” by the central bank or through fractional reserve banking—it sets in motion an exchange of nothing for money and then money for something. This results in an exchange of nothing for something.

An exchange of nothing for something amounts to consumption that is not supported by production. When money “out of thin air” gives rise to consumption that is not supported by preceding production, it lowers the amount of real savings that supports a wealth producer’s production of goods.

This, in turn, undermines his production of goods, thereby weakening his effective demand for the goods of other wealth producers. The other wealth producers are then forced to curtail their own production of goods, thereby weakening their effective demand for the goods of yet other wealth producers. In this way, money “out of thin air” that destroys savings sets up the dynamics of the consequent shrinkage of the production flow.

To conclude: what enables the expansion of the flow of production of goods and services is savings. It is through savings, which give rise to production, that demand for goods can be exercised. No effective demand can take place without prior production. If it were otherwise, then poverty in the world would have been eradicated a long time ago.

Is it Possible to Quantify Total Real Savings?

Now, even if there were any compelling reason to establish what the status of savings is, the relevant savings measure should be the real one—after all, it is real savings that grow the economy. To be able to calculate real savings one must first establish total real income and total real personal outlays. However, this cannot be done, since it is not possible to add potatoes and tomatoes into a meaningful total. All that one can establish is the amount of money spent, or total monetary expenditure.

It is tempting to suggest that we could ascertain real income and real expenditure if we could somehow establish an average price paid for various goods and services. Such an average, however, cannot be established—try and establish an average from dollars per liter of milk and dollars per ton of iron.

Various mathematical methods employed by government statisticians that supposedly provide the solution for separating the real total from total monetary expenditure are an exercise in wishful thinking.

On this Rothbard writes in Man, Economy, and State,

All sorts of index numbers have been spawned in a vain attempt to surmount these difficulties…arithmetical, geometrical, and harmonic averages have been taken at variable and fixed weights; “ideal” formulas have been explored—all with no realization of the futulity of these endeavors. No such index number, no attempt to separate and measure prices and quantities, can be valid.

According to Mises,

In the field of praxeology and economics no sense can be given to the notion of measurement. In the hypothetical state of rigid conditions there are no changes to be measured. In the actual world of change there are no fixed points, dimensions, or relations which could serve as a standard.

Even government statisticians admit that the whole thing is not real. According to J. Steven Landefeld and Robert P. Parker of the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA),

In particular, it is important to recognize that real GDP is an analytic concept. Despite the name, real GDP is not “real” in the sense that it can, even in principle, be observed or collected directly, in the same sense that current-dollar GDP can in principle be observed or collected as the sum of actual spending on final goods and services in the economy. Quantities of apples and oranges can in principle be collected, but they cannot be added to obtain the total quantity of “fruit” output in the economy.1

Now, since it is not possible to quantitatively establish the status of the total real goods and services, obviously various data like real income, real personal consumption expenditure, or real GDP that government statisticians generate shouldn’t be taken too seriously. The data that is generated by means of mathematical methods is just a fiction.

- 1. J. Steven Landefeld and Robert P. Parker, “Preview of the Comprehensive Revision of the National Income and Product Accounts: BEA’s New Featured Measures of Output and Prices” in Survey of Current Business, July 1995.

Tags: Featured,newsletter