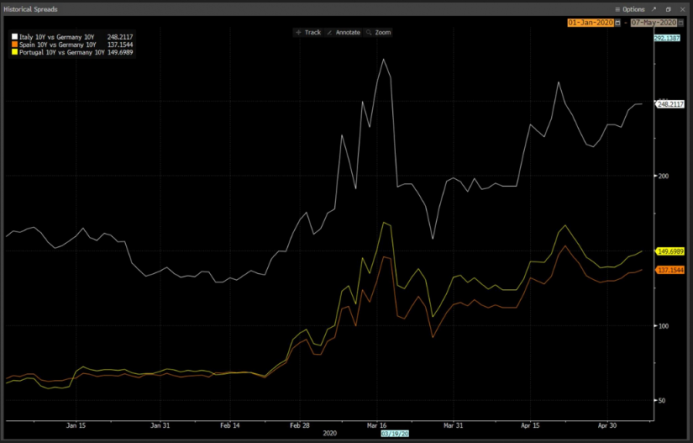

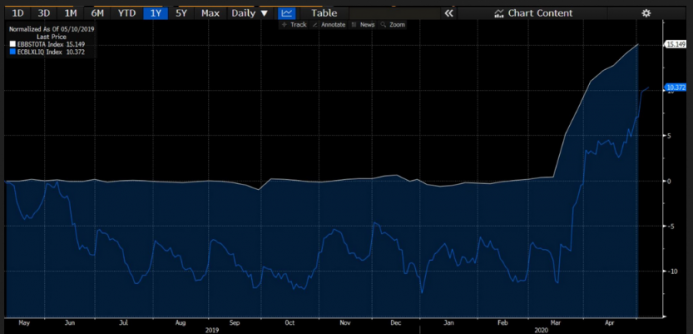

Despite the unprecedented increase in the European Central Bank’s asset purchase program, the spread of southern European sovereign bonds versus German ones is rising. The ECB balance sheet has soared to more than 42 percent of the eurozone’s GDP, compared to the Fed 27 percent of US GDP. However, at the same time, excess liquidity has ballooned to more than €2.1 trillion. The ECB has been implementing aggressive asset purchases as well as negative rates for years, and the reality is that the eurozone economy has remained weak and close to stagnation already in the fourth quarter of 2019. The eurozone’s main problem is that most governments have abandoned all structural reforms and bet all the recovery on monetary policy. The excessive government spending,

Topics:

Daniel Lacalle considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

The ECB has been implementing aggressive asset purchases as well as negative rates for years, and the reality is that the eurozone economy has remained weak and close to stagnation already in the fourth quarter of 2019.

The eurozone’s main problem is that most governments have abandoned all structural reforms and bet all the recovery on monetary policy. The excessive government spending, high tax wedge, and burdens to growth remain, while an increasing percentage of growth is coming from travel and leisure (around 22 percent of gross added value in 2019).

The transmission mechanism of monetary policy is not the problem. Banks are eager to lend and businesses and families have no problem accessing credit. The problem is that the eurozone leaders and central bank managers believe that the eurozone’s challenges are demand problems, when there is evidence that the output gap was very small if existent at all. If there was any evidence, it is that monetary policy in the eurozone did not work as an incentive for productive investment and growth, but rather as a perpetrator of massive imbalances from almost bankrupt governments.

With the crisis of COVID-19, the eurozone finds itself caught between a rock and a hard place. Its fiscal and monetary policy will perpetuate overcapacity in the wrong sectors and excessive government spending, while its tax policy will likely drive innovation, technology, and productive investments further away.

Now that the European Commission has allowed partial nationalizations of industries, the road to permanent stagnation has been paved. First, governments ignore the risks of the pandemic. Then, they close the economy by government decision. Then, they announce tighter controls on foreign investment and capital inflows…and present themselves as the solution.

The eurozone seems to want to use the COVID-19 crisis to advance its interventionist agenda and its so-called Green Deal strategy. The problem is that higher government intervention in the economy will likely lead to more malinvestment, higher unemployment, and lower growth.

The ECB can disguise the risk for a while, but the reality of the mounting debt and tax burden ahead is probably going to end in a debt crisis. This could put the entire European Union at risk as governments in the northern countries are passed the bill for the excess spending of some southern members.

Monetizing risk will not eliminate it. The euro will lose importance as a global reserve currency, and its utilization in cross-border transactions may fall further, leading to a currency crisis just as the debt burden soars.

Originally published at Dlacalle.com

Tags: Featured,newsletter