In a world dominated by mobile capital, mobile capital is the comparative advantage. Defenders and critics of “free trade” and globalization tend to present the issue as either/or: it’s inherently good or bad. In the real world, it’s not that simple. The confusion starts with defining free trade (and by extension, globalization). In the classical definition of free trade espoused by 18th century British economist David Ricardo, trade is generally thought of as goods being shipped from one nation to another to take advantage of what Ricardo termed comparative advantage: nations would benefit by exporting whatever they produced efficiently and importing what they did not produce efficiently. While Ricardo’s concept of

Topics:

Charles Hugh Smith considers the following as important: corporate profits, Corporate tax, Featured, newsletter, The United States

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

If trade numbers more accurately accounted for how products are made, it is possible that the United States would not have any trade deficit at all with China.The problem, in short, is that trade figures are currently calculated based on the assumption that each product has a single country of origin and that the declared value of that product goes to that country.

Thus, every time an iPhone or an iPad rolls off the factory floors of Foxconn (Apple’s main contractor in China) and travels to the port of Long Beach, California, it is counted as an import from China, since that is where it undergoes its final “substantial transformation,” which is the criterion the WTO uses to determine which goods to assign to which countries.Every iPhone that Apple sells in the United States adds roughly $200 to the U.S.-Chinese trade deficit, according to the calculations of three economists who looked at the issue in 2010. That means that by 2013, Apple’s U.S. iPhone sales alone were adding $6-$8 billion to the trade deficit with China every year, if not more.A more reasonable standard, of course, would recognize that iPhones and iPads do not have a single country of origin. More than a dozen companies from at least five countries supply parts for them. Infineon Technologies, in Germany, makes the wireless chip; Toshiba, in Japan, manufactures the touchscreen; and Broadcom, in the United States, makes the Bluetooth chips that let the devices connect to wireless headsets or keyboards.Analysts differ over how much of the final price of an iPhone or an iPad should be assigned to what country, but no one disputes that the largest slice should go not to China but to the United States. That intellectual property, along with the marketing, is the largest source of the iPhone’s value.Taking these facts into account would leave China, the supposed country of origin, with a paltry piece of the pie. Analysts estimate that as little as $10 of the value of every iPhone or iPad actually ends up in the Chinese economy, in the form of income paid directly to Foxconn or other contractors.

|

Where is the “free trade” in a world in which the comparative advantage is held by mobile capital? And what gives mobile capital its essentially unlimited leverage? Central banks issuing trillions of dollars in nearly-free money to banks and other financial institutions that funnel the free cash to corporations and financiers, who can then roam the world snapping up assets and arbitraging global imbalances with nearly-free money.

There’s nothing remotely “free” about trade based not on Ricardo’s simple concept of comparative advantage but on capital flows unleashed by central bank liquidity.

|

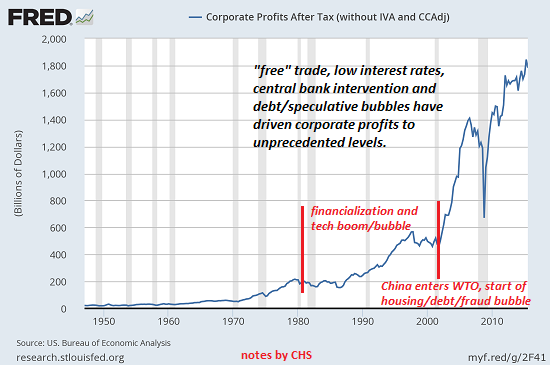

Corporate Profits after Tax, 1950 - 2017(see more posts on corporate profits, Corporate tax, ) |

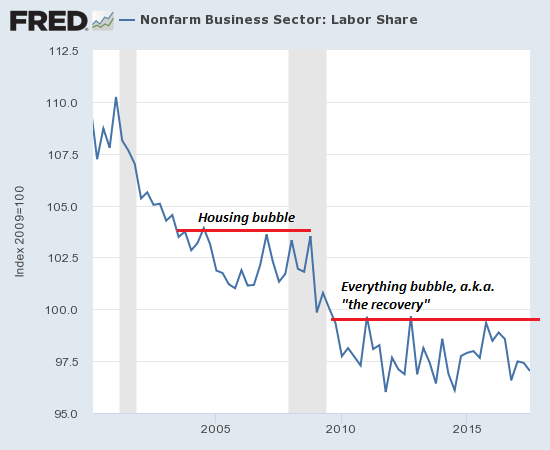

| The gains reaped by mobile capital flow to those who control mobile capital: global corporations, financiers and banks. No wonder labor’s share of the economy is stagnating across the globe while corporate profits reach unprecedented heights. |

Labor Share - Nonfarm Business Sector, 2005 - 2017 |

Tags: corporate profits,Corporate tax,Featured,newsletter