Switzerland: A Test Bed for Radical Ideas The ‘Sovereign money’ initiative, to be voted on in June, aims at a fundamental reform of the Swiss monetary system. In a nutshell, the initiative asks that the creation of money and the granting of loans be separated by barring commercial banks from creating deposits through lending. According to the initiative’s promoters the “Swiss National Bank (SNB) should be the sole organisation authorised to create money – not only cash and coins, but also the electronic money in our bank accounts”. Moreover, the SNB would be responsible for implementing a form of ‘helicopter money’, distributing funds directly to the federal and cantonal governments and even to individual citizens. A

Topics:

Nadia Gharbi considers the following as important: 2) Swiss and European Macro, Featured, Macroview, newslettersent

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Mark Thornton writes Is Amazon a Union-Busting Leviathan?

Switzerland: A Test Bed for Radical Ideas

The ‘Sovereign money’ initiative, to be voted on in June, aims at a fundamental reform of the Swiss monetary system. In a nutshell, the initiative asks that the creation of money and the granting of loans be separated by barring commercial banks from creating deposits through lending. According to the initiative’s promoters the “Swiss National Bank (SNB) should be the sole organisation authorised to create money – not only cash and coins, but also the electronic money in our bank accounts”. Moreover, the SNB would be responsible for implementing a form of ‘helicopter money’, distributing funds directly to the federal and cantonal governments and even to individual citizens.

A Drastic Change to the SNB’s Monetary Policy

Should the referendum be carried, its impact on the SNB would not be neutral. The way the SNB conducts its monetary policy would change, as it would need to target monetary aggregates, a monetary policy style the central bank abandoned in 1999. Moreover, the SNB would risk losing some of its independence, as it would be financing public expenditure directly.

Probability of Success is Low, but…

The Federal Council (central government), the parliament and the SNB have all come out in opposition to the sovereign money initiative. On balance, our baseline expectation is that the sovereign money initiative will be rejected. However, surprises are always possible. This is why we are taking a closer look at what would happen if the sovereign money initiative were to pass.

Investment Conclusions

If the sovereign money initiative were to be accepted by Swiss voters, Switzerland would become a large-scale laboratory for an untried monetary system. The economic consequences are difficult to predict, but the country would likely plunge into a period of uncertainty. How the Swiss franc would react in the short term is not clear cut. There are two possible scenarios: (1) If the SNB is not able to engage in FX interventions and if international investors continue to consider Swiss franc-denominated deposits as a safe haven asset, there would likely be some upward pressure on the franc. (2) By contrast, if the SNB needs to sell its FX reserves or investors lose some of their confidence in Switzerland, the value of the franc would likely diminish. At least initially, the depreciation of the Swiss franc could benefit some Swiss equities via increased reported sales and currency effects. Swiss banks would be hurt were the referendum to pass. The intermediary function played by banks in the monetary system would be impaired, with the risk of creating upward pressure on Swiss long-term rates. Importantly, the precise impact on Swiss assets would depend mainly on the new system’s reach and the length of transition to it.

Rising Public Interest on Monetary Policy Issues

The global financial crisis forced several central banks around the world to rethink the way they conduct monetary policy. The Federal Reserve engaged in large-scale asset purchases starting in late 2008 to fulfil its statutory mandate to achieve maximum employment and price stability. The European Central Bank introduced a number of non-standard monetary policy measures with the aim to safeguard its primary objective of price stability and to ensure monetary policy transmission. The Bank of Japan launched a “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing with Yield Curve Control” policy in an effort to boost the moribund Japanese economy.

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) also pushed the limit beyond what could normally have been expected to stabilise price developments and support economic activity. Against the backdrop of a sharp appreciation of the Swiss franc, the SNB resorted mainly to interventions in the foreign exchange (FX) market, supplemented by a minimum exchange rate of CHF1.20 against the euro that it introduced on 6 September 2011. The minimum exchange rate was discontinued on 15 January 2015, leading to the ‘Frankenshock’ that saw the Franc climb almost to parity with the euro. Since dropping a set minimum exchange rate, the SNB’s monetary policy has relied mainly on two key elements: a negative interest rate on sight deposits (-0.75%) and interventions in the FX market.

The global financial crisis had the effect of raising the level of public interest in monetary policy issues. Increasing liquidity injections by central banks and the interaction between central banks and commercial banks has been a key topic. In Switzerland, the ‘Sovereign money’ initiative (Vollgeldinitiative or Monnaie pleine), which attracted enough signatures (100,000 people) to ensure Swiss voters will vote in a referendum on the issue in June, aims at a fundamental reform of the Swiss monetary system. If the referendum is carried, it would have a direct impact on the way the SNB conducts its monetary policy.

In a nutshell, the initiative asks that the creation of money and the granting of loans be separated, barring commercial banks from creating deposits through lending. According to the initiative’s promoters, the “SNB should be the sole organisation authorised to create money – not only cash and coins, but also the electronic money in our bank accounts” and “the banks would provide all the services as they do now, including bank accounts, payment transactions and loans. They just will not be able to create money anymore”.

This implies that banks would no longer be able to use a fraction of sight deposits to finance their lending activities, as they currently do. All sight deposits in Swiss franc in Switzerland would have to be entirely kept as reserves at the SNB, meaning there would be a reserve requirement of 100%. Through this measure, the initiative’s backers aim to reinforce financial stability as they see money creation by commercial banks as the main cause of financial crises. The idea of a 100% reserve backing for deposits is not new. It was put forward in the 1930s by a group of US-based economists in the so-called ‘Chicago Plan’. However, the sovereign money initiative goes much beyond what would be the equivalent of a full reserve requirement as it would give full control of sight deposits by the central bank.

After the financial crisis of 2007-2008, the idea of a 100% reserve requirement resurfaced in several quarters. The International Monetary Fund published a paper called, Chicago Plan revised, in 2012. The arguments for and against a 100% reserve requirement have also been discussed by parliaments in several countries, although no country has actually adopted such a requirement. The Swiss Federal Council (central government), the parliament and the SNB have all come out in opposition of the sovereign money initiative, but Swiss citizens will have the final say on June 10.

How has Money Evolved in Switzerland?One needs to distinguish between the various types of money. In this particular case, it is important to focus on the distinction between central bank and commercial bank money (in other words, the deposits placed with commercial banks). Central bank moneyThe SNB is responsible for creating central bank money, also referred to as the monetary base (M0). The monetary base currently amounts to approximately CHF546bn, composed of banknotes in circulation The monetary base is subject to the risk of inflation, but apart from this it is practically risk free. When the SNB purchases foreign currency or Swiss franc-denominated securities from a commercial bank, it credits the amount paid to the sight deposit account of the bank concerned in Swiss francs. If the SNB wants to reduce the amount of central bank money, it can conduct the opposite operation. It sells foreign currency or Swiss franc-denominated securities to banks and charges the corresponding amount to their sight deposit accounts. The SNB can thus increase or decrease the volume of central bank money at will. In the wake of the financial crisis, the SNB substantially increased its monetary base to provide the money market with liquidity and to counter any unwarranted appreciation of the Swiss franc. To do this, the SNB has made massive purchases of foreign currency from banks. This has translated essentially into a rise in sight deposits held by domestic banks at the SNB (see Chart 1). |

Switzerland – Breakdown(Central Bank Money), 1990 - 2018 |

Commercial bank money

Deposits held by commercial banks are distinct from central bank money in several aspects. The creation of deposits by commercial banks is closely linked to the granting of loans. When a bank provides a loan, it credits the amount in the form of a deposit to the customer’s account. Importantly, commercial banks do not need to hold an equivalent value of central bank money when they grant a loan. This is what is known as the ‘fractional reserve system’, as only a fraction of customer deposits have to be covered by central bank money. The sovereign money initiative aims to abolish this fractional reserve system to prevent bank runs and financial bubbles.

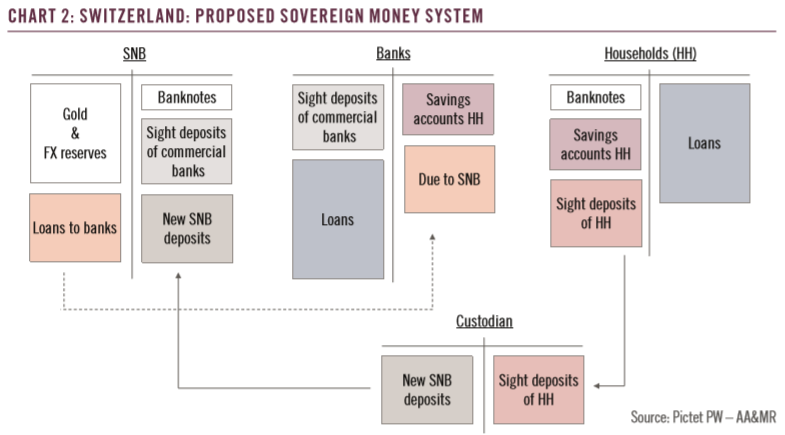

| Deposits are subject not only to the risk of inflation, but also to credit risk. As things stand, if a bank becomes insolvent, customers’ claims to central bank money cannot be redeemed or can be redeemed only up to a maximum amount covered by the deposit guarantee scheme. In Switzerland, the national deposit guarantee scheme covers a maximum of CHF100,000 per customer in the event of a bank failure. The initiative promises absolutely secure deposits. Bank deposits would be converted into central bank money (what the proponents of the initiative call ‘sovereign money’) and all sight deposits would be transferred outside commercial banks’ balance sheets to be kept as separate sovereign money accounts at the SNB. To grant new loans, banks would first have to find funding resources in the market, (e.g. by attracting term or saving deposits or by raising bonds, or if deemed appropriate, by borrowing from the SNB, see Chart 2). |

Switzerland- Proposed Sovereign Money System |

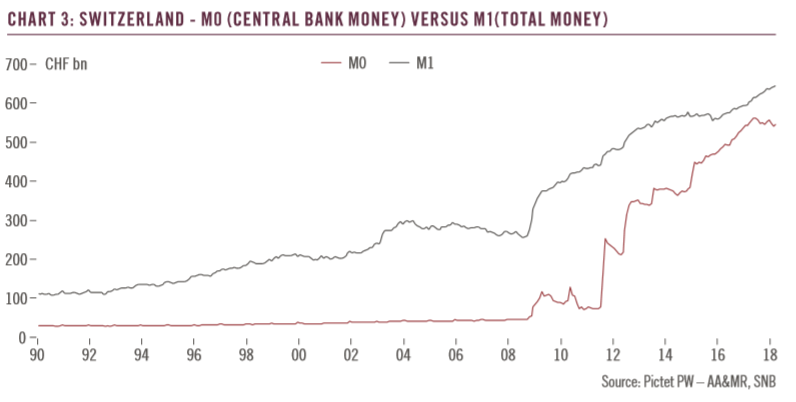

| Money created by commercial banks can be estimated by looking at the difference between the narrow monetary aggregate (M1) and the monetary base (M0). In recent years, this shows that money creation by commercial banks in Switzerland has decreased (see Chart 3). |

Switzerland - M0 (Central Bank Money) Versus M1(Total Money), 1990 - 2018 |

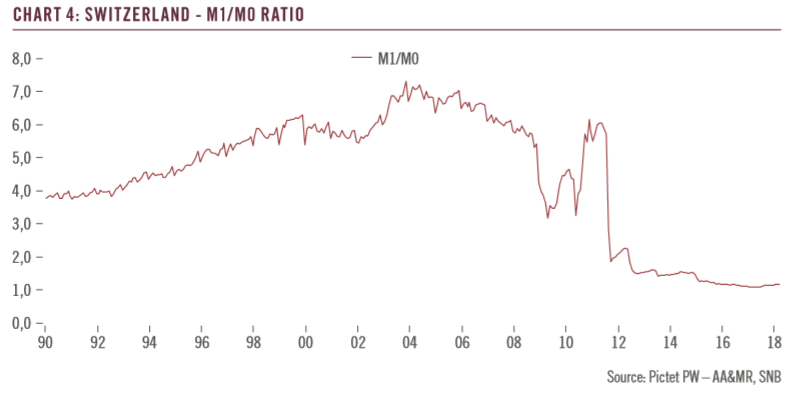

| While Swiss commercial banks have been creating less money, the SNB has been creating more. As a consequence, deposits are currently close to 100% covered by reserves, as shown by the ratio of M1/M0 which is close to one (see Chart 4). |

Switzerland - M1/M0 Ratio, 1990 - 2018 |

Significant Impact on SNB’s Monetary Policy

The acceptance of the sovereign money initiative would result in a change of monetary policy style. Indeed, the SNB would no longer fix a rate of interest but target monetary aggregates instead, an approach it abandoned at the end of 1999 (see Table) mainly for two reasons, according to the SNB’s former chief economist Georg Rich . First, Rich believed, “a policy of steady expansion of the money supply was not considered an optimal strategy for all circumstances as it prevented the SNB from reacting to major unexpected shocks to the economy”. Second, wrote Rich, “a steady expansion in the monetary policy base also turned out to be inadequate in stabilising cyclical fluctuations in economic activity and the inflation rate ” *.

Since 2000, the SNB monetary policy strategy has been based on three key factors: (1) a medium-term inflation forecast; (2) the central bank’s definition of price stability (according to the bank itself, “the SNB equates price stability with a rise in the national consumer price index CPI of less than 2% per annum”); and (3) a target range for the threemonth Swiss franc Libor. The basic objective of the SNB’s monetary policy, ensuring price stability, has remained unchanged.

As has been the case with other central banks, the global financial crisis has pushed the SNB to innovate the way it conducts its monetary policy and to adopt unconventional policy tools. But central banks’ actions have been increasingly called into question and new policy alternatives have been floated (for example, asset price targeting, nominal GDP targeting and flexible inflation). Adoption of the sovereign money initiative would constrain the SNB in its future monetary policy choices and would probably complicate its mandate. Moreover, several aspects of the initiative remain unclear. Calling for the proposal to be rejected, the SNB has mentioned that there is uncertainty on “how a restrictive monetary policy (i.e a reduction in money supply) would be carried out effectively. The SNB would hardly in a position to reclaim money from the Confederation, the cantons or the country’s citizens” (see SNB press release: “Swiss sovereign money initiative: frequently asked questions”). What would happen to existing SNB reserves is not specified in the initiative either. There would also be a question mark over the independence of the SNB, as the central bank would be distributing funds directly to the federal and cantonal governments, and even to citizens.

The SNB’s Firm Opposition

The Federal Council and the Swiss parliament have recommended that the sovereign money initiative be rejected and have not come up with a counterproposal. The SNB does not usually make pronouncements on essentially political issues, but given the potential impact on its role and on the Swiss monetary system as a whole, it has also come out in opposition to the initiative (see SNB press release: “Why the SNB opposes the Swiss sovereign money initiative”). Among the main arguments against the initiative, the following are worth mentioning:

- “There is no fundamental problem in the current set-up that needs to be fixed… The SNB can already steer demand for money and credit via interest rates”.

- “The proposed reform would politicise and complicate the implementation of monetary policy”.

- “It would result in a concentration of tasks at the central bank that would jeopardise monetary policy independence and the fulfilment of the SNB’s mandate”.

- “The ‘debt-free’ issuance of central bank money would erode the SNB’s balance sheet and weaken confidence in the Swiss franc”.

- “Interventions in the foreign exchange market would not actually be allowed under a sovereign money system, as the creation of money in the context of foreign exchange market interventions is not ‘debt free’.

- “A sovereign money system would not prevent credit cycles or asset bubbles. Improved instruments are now available to ensure financial stability: these include capital requirements and ‘too big to fail’ regulations”.

Guinea-Pig Switzerland

If the initiative were to be accepted, Switzerland would become a large-scale laboratory test untried anywhere else to see if a country can completely change its financial system. The way the SNB conducts its monetary policy would change significantly. As we mentioned, the SNB would have to re-adopt a monetary policy approach that was abandoned almost 20 years ago. The economic consequences of a change to a sovereign money system are difficult to predict, but Switzerland would likely be plunged into a period of uncertainty. If the prosperity of Switzerland were threatened, the safe haven status of the Swiss franc could be undone.

In the short run, the reaction of the Swiss franc is not clear cut, as the initiative does not clearly specify to what degree the SNB could engage in FX intervention, nor what would happen to the SNB’s existing stock of foreign currency investments. Two possible scenario emerge for the Swiss franc in the event of the referendum passing. If the SNB were unable to engage in FX interventions and if international investors were to continue to consider Swiss franc-denominated deposits as a safe haven asset, there would likely be some upward pressure on the franc.

By contrast, if the SNB needed to sell its FX reserves and investors lost some of their confidence in Switzerland, the value of the franc would likely diminish. The depreciation of the Swiss franc could benefit exporting companies (and thus some Swiss equities) in the short run. However, Swiss banks would be hurt. The average cost of funding for banks would likely rise, denting their profitability. Moreover, unsatisfied clients might be pushed to demand credit in other currencies, creating currency exposures for borrowers (and possibly for banks), something that would not favour financial stability. The intermediary function played by banks in the monetary system would be impaired, with the risk of creating upward pressure on Swiss long-term rates. Importantly, the precise impact on Swiss assets would depend mainly on whether or not the initiative was fully applied: some measures may be watered down, as has been the case with other initiatives voted by the Swiss electorate.

The Federal Council (central government), the parliament and the SNB have all come out in opposition to the sovereign money initiative, but Swiss citizens will have their final say on June 10.

Tags: Featured,Macroview,newslettersent