The minor concessions continued in the revised plan presented to the European Commission are unlikely to dissuade Brussels from launching sanctions. In a letter to the European Commission on 13 November, the Italian government confirmed that it would aim for a budget deficit at 2.4% of GDP in 2019 and reasserted its real growth forecast of 1.5% for next year. Rome made only minor concessions to Brussels’ demand that it revise its fiscal plan. It committed to raising its privatisation efforts to 1% of GDP in 2019. And to reassure the Commission on the 2.4% deficit, it hinted at introducing safety clauses to be triggered should the deficit look like going higher. The question now is how the European Commission reacts

Topics:

Nadia Gharbi considers the following as important: 2) Swiss and European Macro, Featured, Italian budget, Italian economy, Italian politics, Macroview, newsletter, Pictet Macro Analysis

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

The minor concessions continued in the revised plan presented to the European Commission are unlikely to dissuade Brussels from launching sanctions.

In a letter to the European Commission on 13 November, the Italian government confirmed that it would aim for a budget deficit at 2.4% of GDP in 2019 and reasserted its real growth forecast of 1.5% for next year. Rome made only minor concessions to Brussels’ demand that it revise its fiscal plan. It committed to raising its privatisation efforts to 1% of GDP in 2019. And to reassure the Commission on the 2.4% deficit, it hinted at introducing safety clauses to be triggered should the deficit look like going higher.

The question now is how the European Commission reacts to the minor concessions made by the Italians. While Italy’s response is a small step in the right direction, it will probably not be enough to satisfy the Commission’s demands. Fundamentally, the Italian government’s original 2019 draft budget plan that was rejected by the Commission in October remains unchanged.

The Commission now has to decide whether to launch an Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP). Based on the draft budget, rather than 2.4%, the Commission estimates that Italy’s 2019 deficit will be very close to the 3% of GDP maximum allowed under the European Stability Pact. This would justify launching an EDP. By 30 November at the latest, the Commission will release its final opinion on the 2019 Italian Draft Budget Plan. If the conclusion is that there is serious risk it does not comply with European rules, a so-called ‘Article 126 (3) TFEU report’ could be drawn up. In essence, this report would be the Commission’s assessment of whether or not an EDP is warranted. A previous report released in May 2018 concluded that an EDP against Italy was “not warranted at this stage” and that the country was “broadly compliant with the preventive arm of the Pact in 2017”. The timing of a new report is unclear at this stage, but could be released as early as November 21 when European Commissioners will meet to discuss EU countries’ draft budget plans for 2019 in general. If an EDP is launched, Italy will then need to adopt a set of EC’s recommendations within three to six months.

| Italy could be sanctioned if the deficit is not reduced according to the Commission’s recommendations. This has never happened to a euro area country but, in principle, sanctions could be imposed on a gradual basis, beginning with the obligation to lodge a non-interest bearing deposit of 0.2% of GDP. This deposit will be converted into a fine if the deficit recommendations are not met. The Commission can impose a fixed part of 0.2% of GDP (which would amount to EUR3.5bn in the case of Italy) plus a variable component, for a maximum total of 0.5% of GDP per year. Furthermore, the Commission can suggest suspending commitments or payments of European Structural and Investment Funds to Italy (Italy has been allocated EUR42.77bn over the period from 2014-2020). Immediate sanctions are possible (but not automatic) upon a request from the Commission once an EDP procedure is launched.

The combination of national and European politics makes the current situation highly complex and uncertain. Clearly, finding a compromise between Italy and the rest of the EU will be a hard task. But since the European Commission lacks the means to force the Italian government to back down on its 2019 budget, markets, opinion polls and economic factors rather than Brussels could make the difference, as we argued in previous Flash Notes. The amount of pressure markets exert will depend largely on how the Italian government responds. |

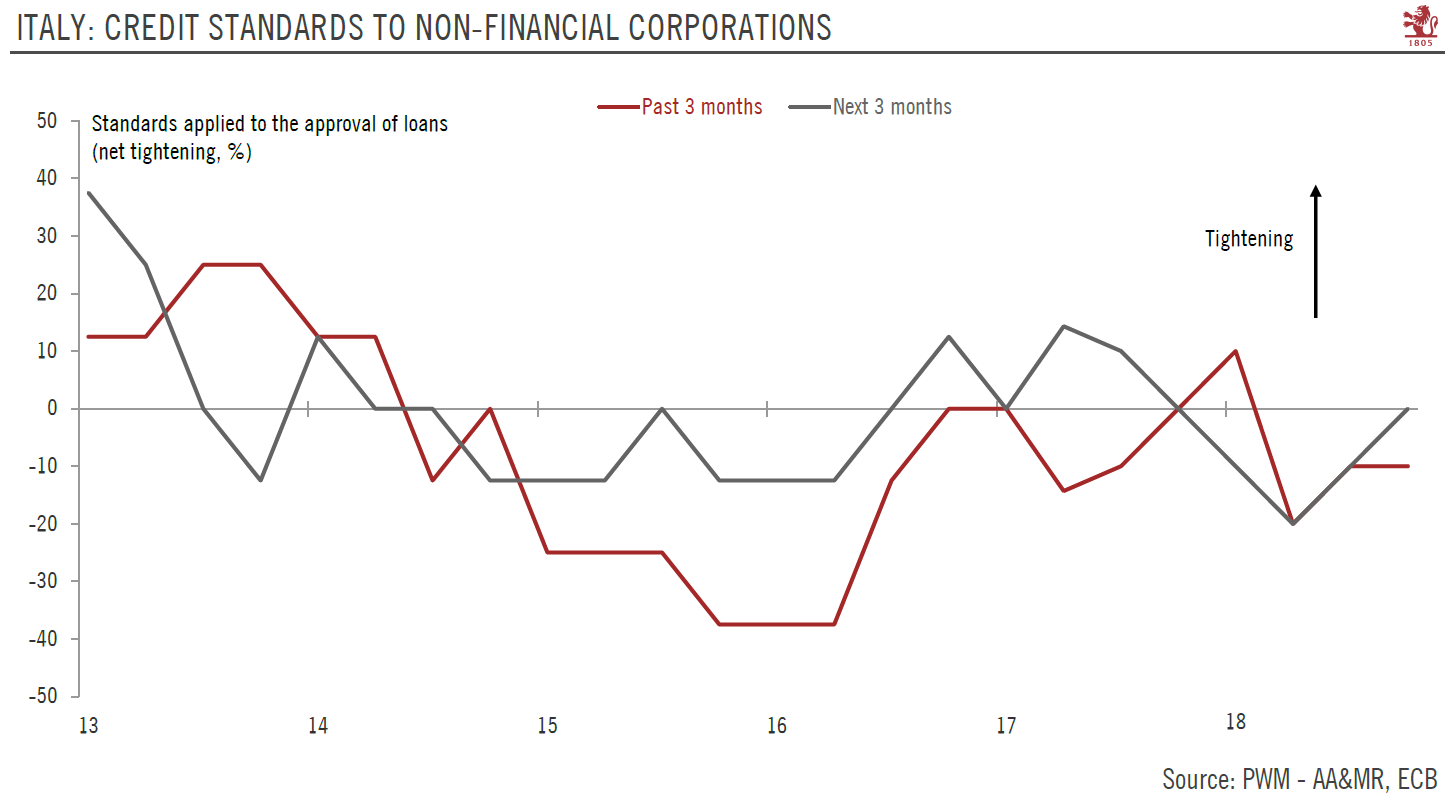

Italian: Credit Standards to Non-Financial Corporations 2013-2018 |

Our central scenario is for tensions between the European Commission and the Italian government to last even beyond the eventual approval of a budget by the Italian parliament at the end of this year. This means recurrent volatility spikes, with financial conditions deteriorating (or at best stabilising)—but with only limited contagion to other euro area peripheral bond markets.

The main idiosyncratic risk to Italy’s growth outlook remains the pass-through of higher government yield spreads to actual lending rates. The longer it takes for this government to change tack, the higher the risk of significant damage to an already weakening economy.

The ECB’s latest bank lending survey already shows a tightening of credit standards in Italy (see Chart below). Italian growth stalled in Q3, leaving the economy still 5% smaller before the 2008 financial crisis. Forward-looking indicators point to further weakness in Q4.

Tags: Featured,Italian budget,Italian economy,Italian politics,Macroview,newsletter