Extracting Meaning from PPP “An alternative exchange rate – the purchasing power parity (PPP) conversion factor – is preferred because it reflects differences in price levels for both tradable and non-tradable goods and services and therefore provides a more meaningful comparison of real output.” – the World Bank Headquarters of the World Bank in Washington. - Click to enlarge We have it on good authority that the business of ending poverty is quite lucrative for its practitioners (not least because employees of multilateral organizations such as the IMF and the World bank have to pay no taxes whatsoever on their income – and the perks certainly don’t end there). A number of long-serving employees of the

Topics:

Jayant Bhandari considers the following as important: CHF/JPY, Debt and the Fallacies of Paper Money, Featured, newsletter, On Economy, Periphery Watch

This could be interesting, too:

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Die Performance der Kryptowährungen in KW 9: Das hat sich bei Bitcoin, Ether & Co. getan

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Wer verbirgt sich hinter der Ethereum-Technologie?

Martin Hartmann writes Eine Analyse nach den Lehren von Milton Friedman

Marc Chandler writes March 2025 Monthly

Extracting Meaning from PPP

|

We have it on good authority that the business of ending poverty is quite lucrative for its practitioners (not least because employees of multilateral organizations such as the IMF and the World bank have to pay no taxes whatsoever on their income – and the perks certainly don’t end there). A number of long-serving employees of the institution we have met over time have struck us as quite cynical and not particularly convinced that their efforts in developing countries were achieving much (and it was not for lack of trying). That is of course not the official line and merely represents anecdotal evidence based on a limited sample size. Experience tells us though that we should not dismiss such evidence out of hand – especially not if it rings true. The agency’s views on PPP are a sign that its economists probably don’t get out much. [PT] Photo credit: Simone D. McCourte |

| As time has gone by, people have increasingly chosen to compare the economies of different nations based on purchasing power parity (PPP) rather than nominal exchange rates. PPP provides some interesting information about economies, but when it comes to the larger issues at play, I will put forth a case in the following that it is nominal exchange rates that are of real significance.

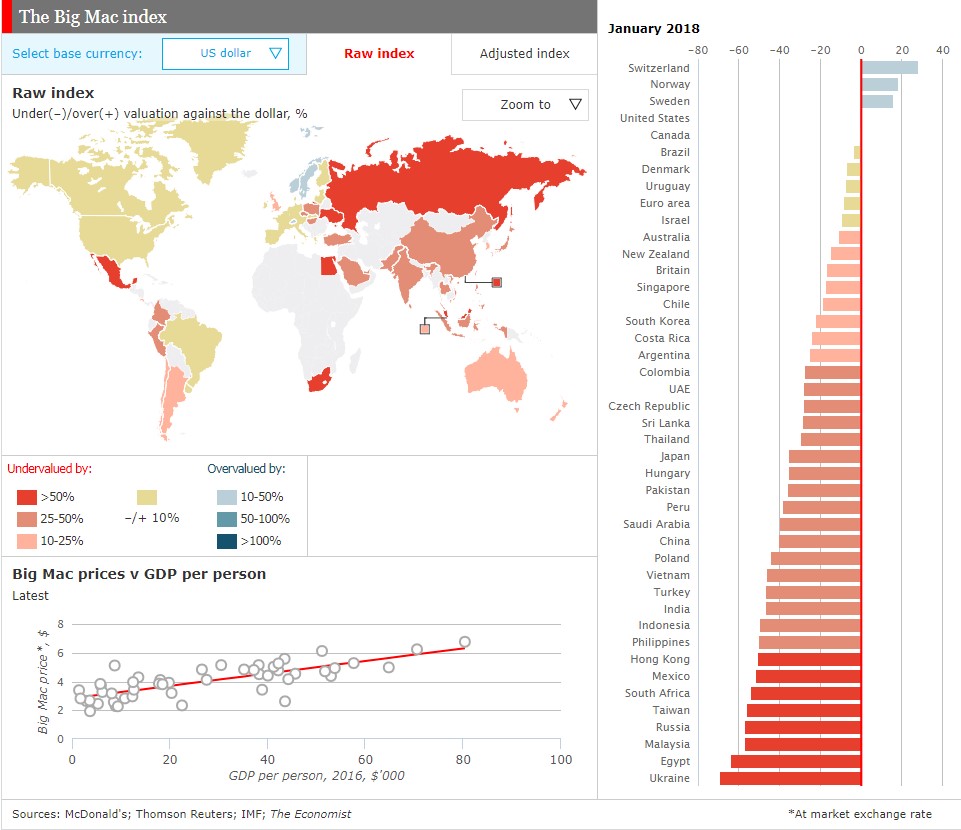

It is also erroneous to expect that nominal exchange rates will move toward convergence in the long-term, i.e., toward equalizing the prices of superficially identical baskets of goods and services as reflected in the PPP measure. Let us define these two terms first. The nominal exchange rate is what the market offers you, but the PPP rate adjusts for differences in the price of a selected basket of goods and services. The Economist has its own measure, the Big Mac Index, as an informal PPP measurement. If a burger in the US is priced at US$5.28 at current exchange rates and in India at US$2.82, the US dollar (USD) is held to be 87% overpriced compared to the Indian Rupee (INR). Based on a basket of goods — intended to reflect real PPP — the USD is 287% more expensive than the INR (or so it is claimed). While the huge difference between the Big Mac Index and real PPP might lead one to dismiss the Big Mac Index as useless, important information is hiding there: As countries like India go up the value chain, the seeming undervaluation of their currencies starts to disappear. In other words, their price structure is such that the more complex products are, the more expensive they are on a relative basis. |

Big Mac Index |

Value Added by McDonald’sOne may well contend that even low value-added products from countries like India — such as vegetables and poultry — are only seemingly cheap, as their quality has been hugely compromised. As you read the following consider whether you would be prepared to pay 287% more if you could be reasonably assured about the quality of chicken and vegetables. McDonald’s offers a huge value-add from an Indian perspective. A McDonald’s restaurant costs between $1 million to $2.3 million. An informal Indian restaurant can be up and running on a roadside for a few hundred dollars, often not even that. Such an Indian restaurant will also pay a fraction of what McDonald’s India pays in wages. |

A McDonald’s restaurant in Mumbai… the company enjoys a great deal of success in India. Its menu is tailored to Indian tastes: some 40% of it are vegetarian, and it lacks beef and pork recipes (which by itself makes Big Mac comparisons slightly dubious). [PT] Photo credit: Frank Bienewald - Click to enlarge |

| When McDonald’s, Pepsi, and Coke came to India, I quickly shifted my preference to them, despite my dislike of fast food. Just the savings in medical bills made McDonald’s much cheaper than seemingly cheap Indian roadside restaurants. Even expensive high-class restaurants in India — with prices as high as those in the West — prove expensive when their low standards of hygiene are taken into account. |

|

| Let us go down even lower in the value-chain, to see if India does become cheaper. The cost of vegetables in India can easily make the USD look expensive. Superficially a PPP over-valuation of 287% of the USD does look like a legitimate proposition.

But there is a catch. Indian vegetables are often washed and grown using sewage water, and chickens are overdosed with antibiotics. If one adds health cost and transaction costs (the latter include the time and effort wasted on searching for good produce), the INR starts to look a lot more expensive relative to the USD. |

|

|

A fish market in Hyderabad that is evidently not exactly the most salubrious seafood trading post in the world. It is probably best avoided, so as to skirt whatever maladies are likely propagating from there. [PT] |

|

|

Some vegetable farmers are a tad too inventive in their efforts to ensure that their produce retain its sales-worthy looks until well after its due date. It is worth noting that inflation is fingered as one of the culprits inspiring these practices. [PT] |

|

Hellish Bus Rides and Schedule-Challenged TrainsWhat about public transportation? A bus ride might cost $0.50 in India compared to $2.50 for a similar distance in the US. But so what? I never use the bus in India, which is often driven by an untrained madman, is crowded, stops for everyone waving at it, takes forever to go from one place to another, is obnoxiously filthy, and is unsafe with metal parts sticking out. When in India, I must take the taxi, which costs more than riding a bus in the US. Despite this, the value of a taxi in India is a lot less than that of a bus in the US. Due to India’s traffic, it takes a lot longer to take me to my destination, and the noise and chaotic conditions keep me from making use of my time to read or to listen to something while I am riding a taxi. Similarly, it is impossible to compare Indian trains with European trains. While I would take a train in Europe, but I almost never do so in India. In order to get a seat at all, one must make reservations months in advance in India. Trains are always late, often by many hours, making it impossible to plan around them. One must compare taking a long distance taxi or a flight in India to taking a train in Europe. India ends up becoming much more expensive. It is easy to stay in basic hotels while traveling in Canada or Europe. Irrespective of where one stays, one can by and large expect clean bathrooms and fresh sheets. That isn’t the case in India, where one has to stay in much higher-class hotels, and even then cannot be entirely sure about the quality of the basics. It is no wonder that most middle class Indians consider it cheaper to go abroad for reasonably convenient vacations. |

An escapee from a mental asylum masquerading as a bus driver in Kolkata – caveat everybody crossing his path… [PT] |

Gently Teasing and Costly Solna MimicryIt is in higher value-added products that the reality become more apparent in objective terms though. As a child, I used to work with my dad at his printing company. Thirty five years ago, we replaced our troublesome USSR-made printing press with a Swedish machine, the Solna. In those days I did not even know yet what a TV was. Our experience with technology was close to negligible. I fell in love with the Solna. It seemed to have a heart and a mind of its own, capable of absorbing and compensating for human errors. Setting it up for a new printing job was a breeze compared to what we used to experience with our USSR-made machine. Once it was set up for printing, it did its job without a hiccup. |

|

| The location and design of every cog and connection seemed to have been well thought-through. One could dismantle a portion, and unlike what used to happen with our previous machine, that portion would slide back into place with precision and a satisfying click.

A year after we had bought the Solna, we were invited to see a Solna look-alike that was manufactured in Delhi. It was a counterfeit. The real Solna and the Indian-made machine looked so much alike that apart from the superficial polish, it was hard to find a difference at first. Every cog was interchangeable. We were able to buy the Indian machine for a fifth of what we had paid for the original Solna. My personal Solna Index seemed to indicate that the Swedish Krona (SEK) was approximately 400% more expensive than the INR. I couldn’t have been more wrong. The Indian machine started giving us small problems from day one. Initially, these were very innocent, isolated issues. A nut would come off, or a thread of a gear would break. Alas, when one deals with thousands of moving parts, such problems soon compound. Despite our best efforts and hoping that after changing a few parts it would actually work just like a Solna, it never did. The Indian-made machine ran for no more than a quarter of the time, while we still had to pay salaries and fixed costs. The machine was rapidly proving to be much more expensive than the original Solna. We sold the Indian machine for scrap a year later. Ironically, today – some 35 years later – the Solna machine we bought is still running. In a few years time, when all life has been extracted from it, it will be sold — not for scrap, but for its parts. When all of this is added up, my own revised Solna Index shows that the SEK is not 400% more expensive than the INR, but actually much cheaper. It is a no-brainer that if the Indian manufacturer had tried to make his machine meet the quality standards of the real Solna, his product would have been much more expensive than the real thing. |

The Solna in action (we bought a single-color version of this machine in the early 1980s). |

Using PPP ProperlyA superficial look at a comparison between PPP and nominal exchange rates convinces manufacturers and service providers in the West to move their production centers to developing countries. They often get badly burnt, but political correctness stops them from naming the key reasons for others to understand. The cost structure of many poor countries — when one adds their very low labor costs with extremely low quality and meager productivity — is actually higher. The PPP measure can help one to imagine and conceptualize several aspects of different societies, but by no means does it indicate that PPP and nominal exchange rates will merge over time. If vegetables are no longer grown using sewage water, the cost of vegetables in India will rise exponentially, and will probably go much higher than in the US. Having visited almost 80 countries and having lived in 7-8, I have mostly found that as a package, contrary to what the PPP measure conveys, poor countries tend to be more expensive than rich ones. Exceptions do of course exist. For example, countries like Thailand, the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, and China are letting my USD go further, although I still have to apply a discount for negative externalities such as crime in the Philippines, and pollution in all these countries. |

The Philippines may be rife with crime, but no-one can accuse the government of mollycoddling criminals, judging from their accommodations. Meanwhile, over in Beijing, breathing can occasionally prove to be quite a challenge. [PT] - Click to enlarge

|

| I find the PPP measure most helpful when comparing rich countries. Switzerland is 97% more expensive than Japan based on the Big Mac Index, and 45% based on real PPP. Hong Kong and Taiwan are also very cheap compared to other developed countries.

Instead of using the PPP measure to imagine a convergence of rich countries with poor ones and hence expect an eventual profit, it might be more useful to bet on the possible convergence between rich countries, which is the reason I like HK$ and Japanese Yen. The situation is similar with the Singaporean dollar and the South Korean won. To what extent can the expensive CHF converge with the USD? I am reminded of a recent coffee-shop experience in Zurich, where the barista ran after me when she spotted a stray droplet on the side of my cup. She wanted to give me a new cup. In most other developed countries, in a similar situation, the barista would have done nothing. The value of such attention to details might not be reflected to a noteworthy degree in the perceived value of a cup of coffee, but it is reflected in the quality of higher value-added products. Often people are indeed prepared to pay a multiple for Swiss products. While Switzerland might look expensive, attention to detail and high quality gives it an unbridgeable, superlative advantage, which might justify much of the currency’s seeming over-valuation in PPP terms. |

CHF/JPY, Jan 1999 - Jan 2018(see more posts on CHF/JPY, ) |

Of course, a Japanese barista would very likely have done the same thing the Swiss one did. So, why is the CHF so much more expensive than Japanese Yen? PPP and nominal exchange rate differences should be used to ask questions rather than perform simplistic linear comparisons.

Tags: CHF/JPY,Featured,newsletter,On Economy,Periphery Watch