Too Big to Fail? Dear Mr. Butler, in your article of 2 October, entitled Thoughtful Disagreement, you say: “Someone will come up with the thoughtful disagreement that makes the body of my premise invalid or the price of silver will validate the premise by exploding.” Back in the late 90s this was actually a fairly well-timed case, as silver eventually rose from a low of around in 2000/2001 to a high of almost in 2011, but we neither bought into the “shortage” story (note: one of the reasons why gold and silver are monetary metals is precisely that their above-ground stock is so large that shortages are extremely unlikely to ever develop), nor the idea that nefarious forces kept prices from rising. This is

Topics:

Keith Weiner considers the following as important: David Scott, Featured, Gold and its price, JP Morgan, newsletter, Precious Metals, silver, silver basis

This could be interesting, too:

investrends.ch writes Hedgefonds-Branche erlebt Gründungsboom – Kapital erreicht Rekordhöhe

investrends.ch writes Millionenstrafe gegen JPMorgan Suisse

investrends.ch writes J.P. Morgan erweitert die ETF-Palette

investrends.ch writes Neue Chief Risk Officer bei JP Morgan Schweiz

Too Big to Fail?Dear Mr. Butler, in your article of 2 October, entitled Thoughtful Disagreement, you say:

Back in the late 90s this was actually a fairly well-timed case, as silver eventually rose from a low of around $4 in 2000/2001 to a high of almost $50 in 2011, but we neither bought into the “shortage” story (note: one of the reasons why gold and silver are monetary metals is precisely that their above-ground stock is so large that shortages are extremely unlikely to ever develop), nor the idea that nefarious forces kept prices from rising. This is not to say that nefarious forces as such don’t exist, only that they probably have better (and more profitable) things to do. Also, since silver was the best-performing commodity from 2000-2011, they would have to be considered pretty inept. |

||||||||||

I will take you up on your request. You state your case in this paragraph:

Silver was in a very strong bull market from 2001 to 2011; the correction since the peak, even though it was quite sizable could well turn out to be part of a longer term bull market. Nothing argues against this idea from a technical perspective. Note the interesting way in which monthly MACD has developed in this context. |

Silver Monthly, 1998 - 2018(see more posts on silver, ) |

|||||||||

In other words, the four issues are:

Let me first address #3. The others are all integral and I will respond to them at length below. When I was about 12, I spent every waking moment teaching myself to program computers. I had this brilliant idea, or so I thought, for how to beat the casino at roulette. Bet $1 on red. If you win, take the profit off the table and bet $1 again. If you lose, bet $2. If you win, you’re even and go back to a $1 bet. If you lose, double again to $4 and so on. The magic is due to the fact that a string of losses becomes more and more improbable the longer it gets. So I wrote a little program to test this scheme. After hundreds or thousands of iterations, you would lose your entire stake. I checked everything; there was no bug in the code. So what caused the losses? Roulette has a 0 and a 00. These numbers are neither red, nor black. The probability of winning a bet on red (or black) is less than 50%, but the payout is only 1 to 1. It doesn’t matter how big a stake you bring to the table (though larger takes longer). Betting on roulette will wipe you out eventually. You might be wondering, what does this have to do with JP Morgan being so big that it need never take losses in silver? The principle is the same. If the bank was net short from Nov 2008 (when you said they became “the new Mr. Big on the short side of silver” after their takeover of Bear Stearns) through April 2011, then it was on the wrong side of a market that moved from $8.30 to $49.80. There is no protection for the big, the medium, or the small. Betting wrong brings losses to anyone. If the argument is that JP Morgan is so big, that it could just short more silver then I have two responses First, please read the above roulette story. Second, the price of silver did go up more than $40. Whatever hypothetical power the bank is supposed to possess, it did not in fact stop the price from rising almost six-fold. If the argument is that JP Morgan did take a loss, but doesn’t have to report it, then let me just note that a bank that big has many people who know its silver position: traders, accountants, internal and external auditors, directors, regulators, etc. Over a period of years, this must add up to hundreds of people who would be risking their careers and liberty to commit fraud by signing off on financial statements showing a profit in such case of loss. |

JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon. His grin tells us his bank isn’t mired in giant losses on silver positions. - Click to enlarge The bank’s financial statements say the same. The biggest trading loss the company reported in recent years occurred when one of its traders, Bruno Iksil, who became known as the “London whale” took way too large positions in otc credit derivatives and ended up as the “speared whale of London” – mainly because his positions grew so big, he basically was the market. The loss amounted to around $2 billion, which was embarrassing for JPM, but far from threatening its existence. It never reported any significant losses in silver. Photo credit: Yuri Gripas |

|||||||||

Whatever is going on in silver, I would bet an ounce of fine gold against a soggy dollar bill that no bank is committing such a fraud, marking trading losses as gains.

Speculation vs. ArbitrageThe answer why JP Morgan has never taken a loss, and the other three issues also, is simply: the banks are not speculators, but arbitragers. Allow me to give a brief outline of my theory of the market, and by the end it will be clear why I say they are arbitragers. First, let me start with some simple facts that should not be controversial. People buy and sell metal in the spot market, and they buy and sell paper in the futures market. These are separate markets. And they have different prices. For example, as I write this in the late afternoon on 3 October, these are the prices: |

|

Anyone who wants to buy metal will pay $16.703 per ounce (not counting product premium or shipping). Sellers of metal will get $16.684. The spread is 1.9 cents. By contrast, if you call up your futures broker to buy, you pay $16.71 (not counting commissions or exchange fees). If you sell a contract, you get $16.705. The spread is half a penny, much tighter than the spread in spot.

Imagine if you could make 1.9 cents every time one guy sold metal and another bought. Or if you could make half a penny every time traders did it in futures. It’s a smaller profit per ounce, but one contract is 5,000 ounces and many traders throw around blocks of 5 or more contracts.

If you focused on such a business, you would not be trading the price of the metal but the spread. You wouldn’t care if silver went to $50 or down to $5. You make your money every time one trader buys and another sells. You are not a speculator, but a market maker. You are not riding the roller coaster of big up and down moves. You are making a steady, boring income.

So far, we have looked at market making in one market. It also applies across these two markets. For example, suppose someone wants to buy a silver future. You could buy spot silver for $16.684, sell him a future for $16.71, and make a profit of 1.6 cents.

This is called a carry trade. This market maker buys metal, and warehouses it until the contract calls for delivery. For this trade, he makes 1.6 cents per ounce on a trade that is just about two months. 1.6 cents is about 0.1%. Annualized it is about 0.6%.

At the moment, this is not so attractive, as 2-month LIBOR is 1.27%. However, the point is that there is usually a profit to carry metal. This profit is called the basis. My company Monetary Metals publishes daily gold basis charts and silver basis charts.

There are other arbitrages. For example, one could lease out the metal instead of paying to store it (this would, of course, skew the COMEX warehouse statistics, making it appear there’s no metal when the reality is that there is metal but it’s not in the warehouse at that moment). Why would a bank lease metal? To increase its profit, of course. Here is a road map to this trade:

1 Borrow dollars

2 Earn basis

2a Buy physical silver metal

2b Sell silver futures

3 Lease physical silver for the duration

These transactions are simultaneous, so ensure the bank is locking in a known profit. So the profit on this type of carry trade is:

Basis Rate + Lease Rate – Interest Rate

For this example, let’s use a farther out contract as December does not offer much opportunity today. We will use a March contract. A bank can borrow in the inter-bank market, which means we will use the LIBOR rate. 6 month LIBOR is 1.5%. That is the cost of the trade.

The March silver basis is around 1.2%. This is one source of profit. The other is the lease rate. We also publish charts of the silver lease rate. The current silver lease rate (offer, or ask price) is 0.5%. So, for our example, the profit the bank nets on this trade is:

1.2% + 0.5% – 1.5% = 0.2%

With borrowed money. 0.2% risk-free profit, using other people’s money. You may not want to take this on yourself, but the point is that this is a sound trade. The banks can do this all day long, without leading to any kind of collapse. On the other hand, if they are tempted to do longer leases, because the lease rate is higher (right now, it is not) then they can get into trouble. They run the risk that the cost to roll their futures position could go up. And another risk is that LIBOR could rise (it has been rising for years).

Proving a TheoryThis brings us to an interesting point. In physics, when there are two competing theories, scientists look for a case where each predicts the opposite result. Then they perform an experiment and observe the result. For example, Aristotle believed that two rocks of different weights must fall at different speeds. He said that the heavier one should fall faster, in proportion to its greater mass. Galileo believed that they will fall at the same speed. So he took two rocks, one heavier than the other, and carefully dropped them from the Leaning Tower of Pisa. They hit the ground at the same time. Galieo’s theory was proven right, and Aristotle wrong. Later, astronaut David Scott did an experiment in the vacuum on the moon’s surface, and showed that a feather and a hammer fall at the same speed. |

Galileo had the better ideas about physics, particularly with respect to bodies in motion and the forces affecting them. In modern-day gender studies it was found that although gravity mistreats all objects equally, it still has to be classified as a misogynist tool of oppression invented by the patriarchy (just look at these bearded fellows!) and should therefore be banned. Still, Galileo was right. |

| We have two competing theories of bank participation in the silver market. Your theory says that they are speculators, betting on the direction of the price. Not just betting on any direction, but generally that the direction will be down. My theory says that they are primarily arbitragers, indifferent to price, earning a small spread. And there is a case where each theory predicts the opposite behavior. The contract roll. Let me explain.

Futures contracts generally live for 18 months. They come into existence 18 months before they expire. As they approach expiration, there is a deadline called First Notice Day. On or before this day, traders with long positions, who do not have the cash to take delivery, must sell their contracts. If they want to keep their bet going, they can buy another farther-dated contract. Traders who are short, who do not have metal to deliver, must buy their contracts. If they want to keep their bet, they can sell another contract. If the big banks are making a bet on a falling price, then they do not have the metal to deliver and therefore must buy the expiring contract with urgency. Recall from earlier, the price of a silver futures contract is not the same price as the price of silver. Indeed, the price of the Dec silver contract is not the same as the March, the May, or the July 2018 contracts. If there is urgent buying, in size, it will drive up the price of the expiring contract. However, if the banks are arbitragers who have bought physical metal, then they have already locked in their profit. In this case, they are happy to deliver the metal if it comes to it. On the other side of the trade, who are the buyers of all these contracts? Have they got the cash to stand for delivery? Most traders who use futures do so because the market offers leverage. To buy 10,000 ounces of silver metal you need $166,000. To buy two silver contracts, you need only a fraction of that (depending on margin requirements, which change from time to time). The urgent selling of these long speculators would cause the price of the expiring contract to fall. If there is an equal balance, and both shorts and longs are naked, then we would expect mixed results. Sometimes, we should see an expiring contract fall, and other times we should expect to see it rise. Our experiment should look to see what happens to the price of each contract as it nears expiry. There is one last wrinkle. We cannot look at the raw price. The signal we seek may be small relative to the price of silver. We want to look at the difference between the expiring futures contract and the reference price of spot: Future – Spot. This happens to be the basis! We just need to look at the data, to determine which theory is true:

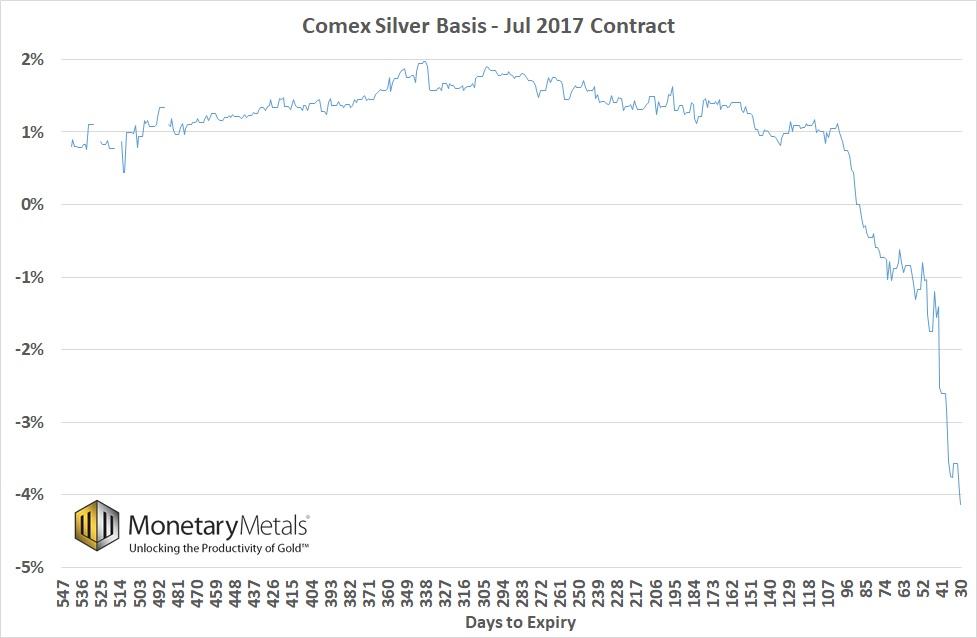

Here is a chart showing one silver contract by itself, to clearly illustrate what the basis looks like over the life of a futures contract. |

Silver Basis, Jul 2017(see more posts on silver basis, ) |

| In this case we can see the contract’s basis falling, indicating that it was long speculators who had to exit, rather than the shorts. However this is only one contract. For a valid experiment, we need more data.

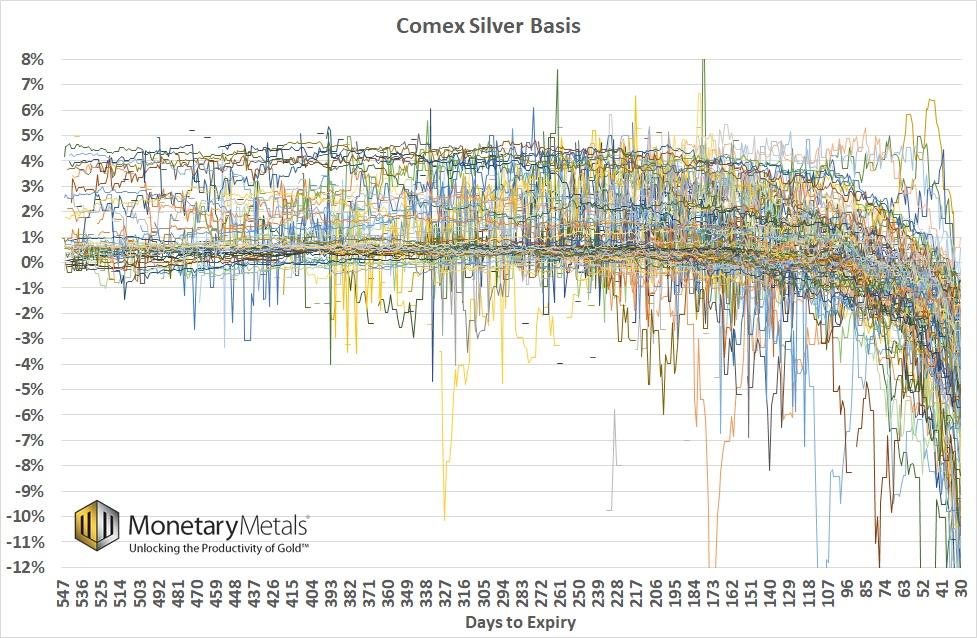

Monetary Metals has calculated a precise value for the basis of every contract going back to 1996. Using this data, we have put together a chart of all 109 silver contracts since March 1996. To make it easier to see, we have aligned all of them by contract age in terms of number of days until expiry on the X axis of the chart. The Y axis shows rise or fall in basis over the life of the contract up to around First Notice Day. This chart makes it possible to visualize the behavior of all contracts. And here is the chart with all contracts overlapping on it, to show the overwhelming evidence in support of the bank-arbitrager theory that puts the bank-speculator theory to bed. |

Silver Basis(see more posts on silver basis, ) |

The fact that all but a handful of contracts plummet is strong evidence that long speculators, those who bet on the rising price, predominate. Shorts are typically arbitragers, not bettors. This is what you would expect in a fiat currency regime, where the risk of a price drop is smaller than the risk of a price explosion. Few traders want to short gold or silver. Those who do, get in and out for a quick tactical trade based on chart patterns or other opportunities that may arise.

Note that there are no contracts which skyrocketed by any definition of that word, although there are 3 contracts which held a positive basis or which rose slightly into First Notice Day. Monetary Metals plans to drill down into these three in a future article.

For those who want to see gold, Monetary Metals has published a similar overlapping graph of all the gold contract bases since 1996 here (free registration required).

Conclusion: The Key

In this September 2013 interview with Sprott Money, you said:

“I can’t figure out why the CFTC is tolerating it [JP Morgan’s dominant position],” […] “I guess I could be wrong. I guess I could be reading the Commitment of Traders wrong”.

I suggest that the key data is not the COT, but the basis. The basis shows us what the CFTC likely can see from auditing the bank’s trading book: JP Morgan is a market-making arbitrager, not a market-moving speculator.

I will end with an offer. Monetary Metals has nearly 3 terabytes of data, containing every COMEX futures and spot metal price in both gold and silver going back 21 years. If you have another specific explanation of how JP Morgan manipulates the market (and which is not invalidated by the graphs above), let’s work to design an experiment. We are happy to query the appropriate data, and publish a graph or graphs that can confirm or disprove your hypothesis.

Tags: David Scott,Featured,JP Morgan,newsletter,Precious Metals,silver,silver basis