The G-20 and Policy Coordination Readers may recall that the last G20 pow-wow (see “The Gasbag Gabfest” for details) featured an uncharacteristic lack of grandiose announcements, a fact we welcomed with great relief. The previously announced “900 plans” which were supposedly going to create “economic growth” by government decree seemed to have disappeared into the memory hole. These busybodies deciding to do nothing, is obviously the best thing that can possibly happen. Yuan, weekly – since the sharp move in USDCNY in August, market participants have begun to worry about the yuan and China’s shrinking foreign exchange reserves – click to enlarge. There have been rumors though that they did at least strike some sort of sub rosa agreement with respect to the future course of yuan manipulation. In other words, some kind of policy coordination between China and other major currency issuers has quite possibly been agreed upon, even if only tacitly. Officially, China merely used the occasion to “reassure trading partners on foreign exchange”: “Chinese policymakers on Thursday ruled out an imminent devaluation of the yuan as they seek to reassure trading partners ahead of the G20 summit that they can manage market stability while driving structural reforms.

Topics:

Pater Tenebrarum considers the following as important: Central Banks, Monetary Metals, On Economy

This could be interesting, too:

Eamonn Sheridan writes CHF traders note – Two Swiss National Bank speakers due Thursday, November 21

Marc Chandler writes Consolidation Featured

Marc Chandler writes Fragile Turn Around Tuesday

Adam Button writes SNB’s Jordan: I’m not sure whether if the terminal rate has been reached

The G-20 and Policy Coordination

Readers may recall that the last G20 pow-wow (see “The Gasbag Gabfest” for details) featured an uncharacteristic lack of grandiose announcements, a fact we welcomed with great relief. The previously announced “900 plans” which were supposedly going to create “economic growth” by government decree seemed to have disappeared into the memory hole. These busybodies deciding to do nothing, is obviously the best thing that can possibly happen.

Yuan, weekly – since the sharp move in USDCNY in August, market participants have begun to worry about the yuan and China’s shrinking foreign exchange reserves – click to enlarge.

Yuan, weekly – since the sharp move in USDCNY in August, market participants have begun to worry about the yuan and China’s shrinking foreign exchange reserves – click to enlarge.

There have been rumors though that they did at least strike some sort of sub rosa agreement with respect to the future course of yuan manipulation. In other words, some kind of policy coordination between China and other major currency issuers has quite possibly been agreed upon, even if only tacitly. Officially, China merely used the occasion to “reassure trading partners on foreign exchange”:

“Chinese policymakers on Thursday ruled out an imminent devaluation of the yuan as they seek to reassure trading partners ahead of the G20 summit that they can manage market stability while driving structural reforms.”

When global stock markets swooned in late August 2015 and again in January 2016, the decline in the yuan’s exchange rate was widely blamed as the cause. Considering various central bank policy decisions announced since the G20 meeting, it does appear as though a coordinated move aimed at halting the yuan’s slide and support wobbly risk asset prices has been underway.

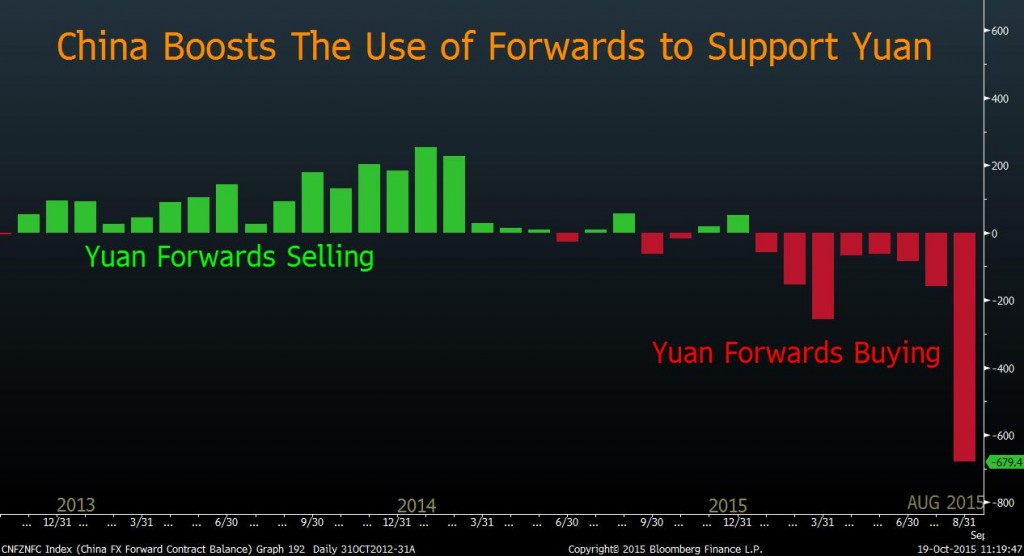

Even the Fed has become a lot more ambiguous about its previously announced rate hike plans. China’s authorities meanwhile have employed all sorts of tricks to hold the yuan up. According to Bloomberg, it has found “more discreet ways to support the yuan” – mainly by employing derivatives. Using forward transactions has two advantages from the perspective of China’s planners: they delay the official recognition of foreign exchange outflows and they don’t need to be reported to the IMF. The result is that they are “hiding the PBoC’s footprints in the financial markets”, as Bloomberg puts it (see also Roger’s article on China’s new ways to lie with numbers).

A surge in yuan forwards buying designed to surreptitiously support the exchange rate; however, the chickens are bound to eventually come home to roost – this is only a delaying tactic – click to enlarge.

A surge in yuan forwards buying designed to surreptitiously support the exchange rate; however, the chickens are bound to eventually come home to roost – this is only a delaying tactic – click to enlarge.

Ahead of the G20 meeting it was vehemently denied that there would be an agreement over exchange rates. China’s finance minister let it be known that such an agreement was “wishful thinking” and “a media fantasy”. However, right after the meeting we could read that “G20 Nations, Including China, Swear Off Currency Devaluations”. So there was no agreement, instead they just held a currency-related oath-taking ceremony.

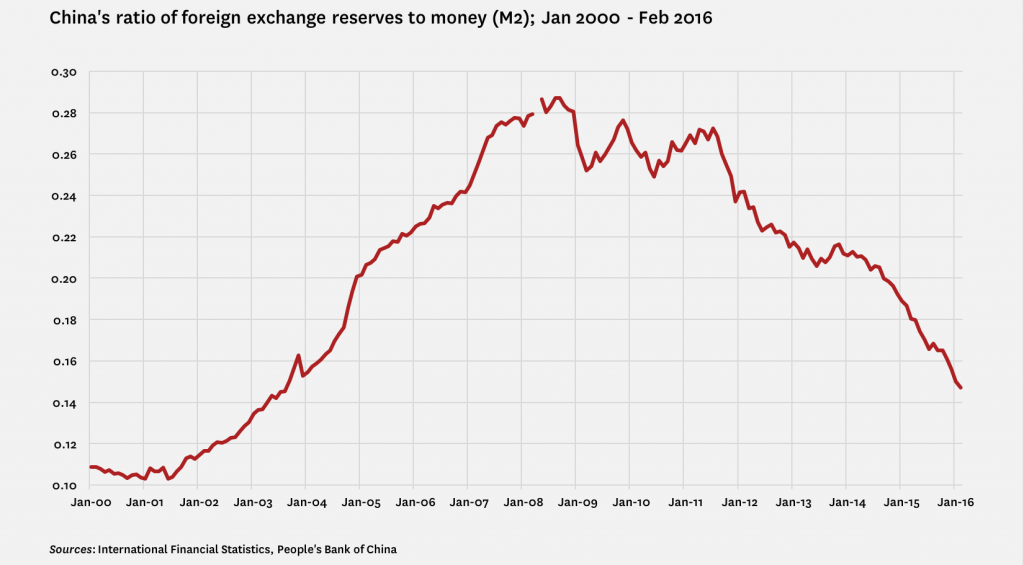

As Carmen Reinhart has recently pointed out, China’s attempt to both expand money and credit at home and keep the yuan at an artificially high exchange rate cannot possibly work. A chart of the ratio of China’s foreign exchange reserves to the broad money supply aggregate M2 illustrates a growing discrepancy – the ratio has in the meantime fallen back to levels last seen in 2003:

The ratio of China’s forex reserves to M2 – click to enlarge.

The ratio of China’s forex reserves to M2 – click to enlarge.

The attempt to artificially support the yuan in order to alleviate short term financial pain seems destined to eventually end up triggering a plethora of “unintended consequences”.

A History of Devastating Failures

History suggests that global monetary policy cooperation in order to artificially prop up or weaken specific currencies invariably leads to major disasters. The most famous example is perhaps the agreement struck between the Federal Reserve’s Benjamin Strong (notorious provider of “coups de whiskey” to the stock market) and BoE chief Montagu Morgan in the 1920s.

The plan was to support the British pound by means of the Fed adopting a looser monetary policy. Britain had gone back to gold parity at a completely unrealistic exchange rate and had implemented policies that were putting additional pressure on the currency. As a result gold started to flow out from Britain at an accelerating pace, so it had to either alter its policies or get outside help. The Fed decided to provide it.

This in turn helped to drive the credit and asset bubble of the roaring 1920s to excessive heights and eventually produced what was arguably the greatest economic and socio-political catastrophe of modern times. As Murray Rothbard writes on the agreement in “America’s Great Depression”:

“Instead of repealing unemployment insurance, contracting credit, and/or going back to gold at a more realistic parity, Great Britain inflated her money supply to offset the loss of gold and turned to the United States for help. For if the United States government were to inflate American money, Great Britain would no longer lose gold to the United States. In short, the American public was nominated to suffer the burdens of inflation and subsequent collapse in order to maintain the British government and the British trade union movement in the style to which they insisted on becoming accustomed.”

Along similar lines, in more recent times there have e.g. been the Plaza and Louvre accords – one of which was designed to weaken the dollar’s exchange rate, while the other was designed to strengthen it after the results of the first accord appeared to have gone too far. The result was not only a period of extreme currency volatility, but an asset bubble that eventually culminated in the 1987 stock market crash and the blow-off in Japan’s stock and real estate markets that peaked in 1989. Whatever short-term objectives were supposedly served by these accords were completely dwarfed by the long term effects.

USD Index (DXY), SPX and Nikkei from 1980 to 1990 – wild swings in the US dollar, accompanied by major asset bubbles – click to enlarge.

USD Index (DXY), SPX and Nikkei from 1980 to 1990 – wild swings in the US dollar, accompanied by major asset bubbles – click to enlarge.

The 1987 crash in turn inspired the so-called “Greenspan put”, and the bubble of the 1990s followed in its wake. Along the way there was the peso crisis of the mid 1990s and the Asian/Russian currency crisis of 97/98, after the currency pegs of the “Asian tigers” gave way. These crises were of course met with even more interventions, which egged on credit and asset bubbles of truly stunning proportions (in this case, interest rate cuts by the Fed in late 1998 were the precursor to the giant blow-off in technology stocks).

These modern-day currency manipulation efforts can essentially be seen as a reaction to the fact that the unfettered fiat money system that has been in place since the early 1970s is producing ever greater imbalances and distortions. It is held that these negative results require additional intervention so as to be “corrected”. One must keep in mind to this that currency manipulation always involves the adoption of specific monetary policies. These will as a rule push interest rates even further away from the natural rate and amplify boom-bust cycles accordingly.

The “Long Run” Has Caught Up With Us

It has turned out that contrary to the famous bon-mot by Keynes, we are actually not “all dead in the long run“. The long-run has apparently caught up with us. Since the bursting of the technology bubble in 2000 we have experienced the biggest expansion in money and credit in history, accompanied by boom-bust phenomena of increasing severity.

These include real estate bubbles of previously unimaginable size all over the world, the 2008 financial crisis, an unprecedented expansion in global debt levels (including government debt that in a number of cases has not only set new peacetime records, but even exceeded previous wartime peaks) and lately the mother of all echo bubbles in risk assets.

And yet, here we are, with economic growth at best anemic for the past seven years (and becoming more so), global trade growth going into reverse, and central banks engaging in utterly insane monetary experiments. Not surprisingly, social and economic upheaval is on the upswing around the world. Eventually there will be one intervention too many and the whole charade will blow up in an unstoppable cascade.

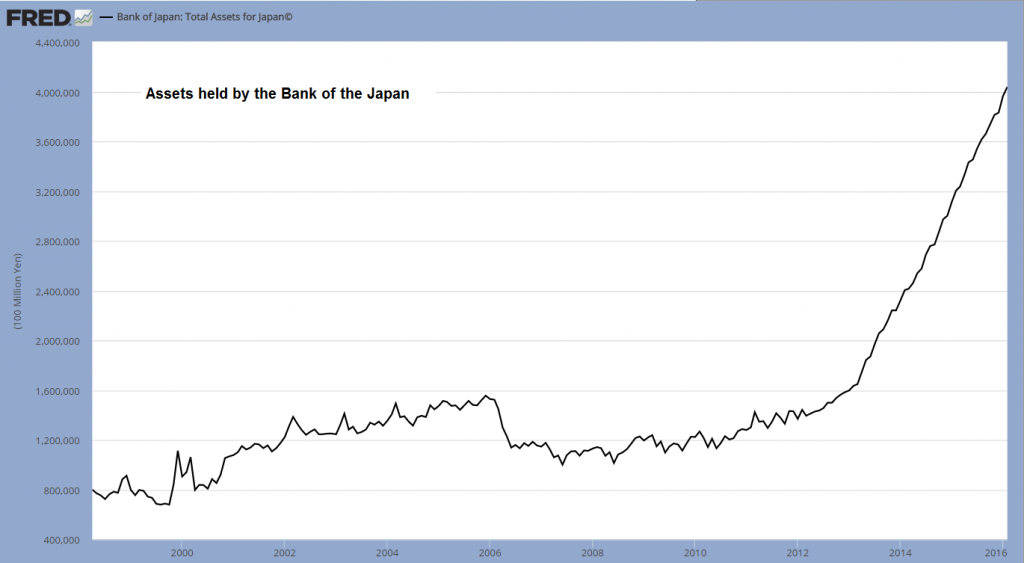

The only question is where and when the unraveling will begin. Japan strikes us as a candidate with good potential for providing the trigger, mainly because its monetary and fiscal policies have become such an overt and breathtakingly enormous Ponzi scheme. By now the BoJ owns about one third of Japan’s giant public debtberg. The old saying that “we owe it to ourselves” finally seems to have come true there (of course, as the saying goes it is simply “too good to be true”).

Assets held by the BoJ – “we owe it to ourselves” – the Japanese government has become the biggest holder of its own debt by means of monetization – click to enlarge.

Assets held by the BoJ – “we owe it to ourselves” – the Japanese government has become the biggest holder of its own debt by means of monetization – click to enlarge.

As Mish recently noted, the BoJ’s massive debt monetization efforts are already beginning to run into unexpected snags. Given that Japan is not only is home to the developed world’s largest domestic debt pile, but is at the same time still the world’s largest creditor, it is easy to see how a crisis of confidence could ripple out from there and engulf the rest of the world. Incidentally, the US played a similar role as an important creditor nation in the 1920s; the repatriation of US investments from Europe in the early 1930s was a major factor in exacerbating a global avalanche of debt defaults.

Conclusion

Looking at the way in which today’s ever more extreme monetary policy measures and interventions are reported and discussed, one could almost get the impression that the philosopher’s stone has finally been found and that wealth can indeed be conjured up ex nihilo at the push of a button. However, this is not the case – on the contrary, the more often these buttons are pushed, the weaker the structure that actually generates real wealth becomes.

We believe a lot of unpleasantness could be avoided if these crazy policies were finally stopped. For a while here would certainly be a period of intense economic pain, but human ingenuity combined with the world’s accumulated real capital should soon restore sound economic growth. In principle, we are actually quite optimistic on that score. After all, even today’s severely hampered market economy still manages to create enough wealth for the world to muddle on.

However, this would also require a profoundly change in thinking. Economic progress cannot be “ordered” from the top by a coterie of planners, regardless of how well-intentioned they may be. Their constant tampering with the market economy must end. It would be best to release these people into the marketplace, where they could put their abilities to good use by serving consumers instead of coercing them.

Charts by: investing.com, Project Syndicate, Bloomberg, StockCharts, St. Louis Federal Reserve Research