Published: Tuesday December 29 2015 The Director of Geneva’s Campus Biotech is creating a new biotechnology and medical technology centre, bringing together different disciplines to find treatments that will save lives and improve the quality of life for patients. Since the beginning of modern pharmacology, the treatment of patients has relied on advances in medicine and biology to devise therapies that can cure or alleviate their conditions. Today, new approaches focus on specific biological targets, identify predispositions to diseases and find personalised treatments that use digital technologies to put patients in control. Campus Biotech, an ultra-modern research centre in Geneva, is aiming to put itself at the forefront of this new approach, bringing together a wide range of skills in biotechnology and medical technology to find cures for diseases that have defeated large drug companies. Its new approach to research and development will create opportunities for collaboration between researchers, technologists, computer specialists and the drugs industry to bring innovative products to market. ‘We are at a turning point in the history of medicine,’ says Benoît Dubuis, Executive Director of Campus Biotech. ‘The confluence of innovations in computing, engineering and biotechnology will revolutionise the treatment of health problems.

Topics:

Perspectives Pictet considers the following as important: carousel, In Conversation With, innovation

This could be interesting, too:

Perspectives Pictet writes House View, October 2020

Perspectives Pictet writes Weekly View – Reality check

Stéphane Bob writes What can investors do in uncertain times?

Stéphane Bob writes Multi-generational wealth

The Director of Geneva’s Campus Biotech is creating a new biotechnology and medical technology centre, bringing together different disciplines to find treatments that will save lives and improve the quality of life for patients. Since the beginning of modern pharmacology, the treatment of patients has relied on advances in medicine and biology to devise therapies that can cure or alleviate their conditions. Today, new approaches focus on specific biological targets, identify predispositions to diseases and find personalised treatments that use digital technologies to put patients in control.

Campus Biotech, an ultra-modern research centre in Geneva, is aiming to put itself at the forefront of this new approach, bringing together a wide range of skills in biotechnology and medical technology to find cures for diseases that have defeated large drug companies. Its new approach to research and development will create opportunities for collaboration between researchers, technologists, computer specialists and the drugs industry to bring innovative products to market.

‘We are at a turning point in the history of medicine,’ says Benoît Dubuis, Executive Director of Campus Biotech. ‘The confluence of innovations in computing, engineering and biotechnology will revolutionise the treatment of health problems. Our goals are to ensure that medicine meets the needs of an ageing population, that it can be financed and that it can respond to new needs such as chronic diseases which now consume so much of health budgets.’

The opportunity to create Campus Biotech came in 2012 when the pharmaceutical giant Merck Serono closed its base in a former industrial area of Geneva, leading to the loss of more than a thousand jobs. To retain their expertise, a consortium backed by the canton of Geneva and the federal government bought most of the building a year later, with plans to open a new type of research hub.

Two universities are at the centre of the project: the University of Geneva and École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne’s technical university – both of which are moving research groups to the campus. Two wealthy philanthropists also contributed: the Bertarelli family, the descendents of Serono’s founder, which has previously endowed neuroscience programmes at EPFL and Harvard; and Hansjörg Wyss, founder of a medical devices business, who is also endowing the Wyss Centre for Bioand Neuro-Engineering at the Campus.

With these resources, the new centre is focusing on neuroscience – a discipline for which both universities are noted. This leadership position was boosted when the European Union decided in 2013 to support EPFL’s Human Brain Project, which aims to stimulate the brain using computers and has also been relocated to the Campus.

Another reason for this focus is that the Campus can unite two approaches to treating neurological conditions: biotech developments of pharmaceuticals; and medtech devices such as the brain implants that now treat Parkinson’s disease. ‘We think that the next generation of treatments will come from the interface between these two approaches,’ says Dr Dubuis. Dr Dubuis believes that the Campus will be able to find market solutions to intractable neurological diseases, especially mental illnesses and those connected with ageing such as Alzheimer’s. ‘Most large pharmaceutical companies have abandoned many of these fields because they see them as too risky. Our collaboration between different disciplines can tackle them.’

In addition to neuroscience, the Campus has a second focus on digital medicine. Masses of health datais generated daily through mobile applications, wearable technologies, computerised records and analytical disciplines such as genomics. Gathering and processing this data using digital forms of R&D such as modelling, simulation and visualisation should provide information that can make treatments smarter.

Opened in May 2015, Campus Biotech already has a workforce of 600, which is expected to climb to more than a thousand. The aim is to foster platforms that are open to anyone to work in – researchers, digital experts,engineers, entrepreneurs and companies. ‘Use labs’ are available for non-employees where they can collaborate on specific projects and return to their normal places of work when they are completed.

Dr Dubuis is well-placed to work on such convergence issues. A chemical engineer by training, his doctorate was in biotechnology. He was Dean of the School of Life Sciences at EPFL and has worked with companies such as Ciba- Geigy and Lonza. He also co-founded Eclosion, the first Swiss Life Sciences seed-fund and incubator which helps researchers transform their laboratory findings into commercial products.

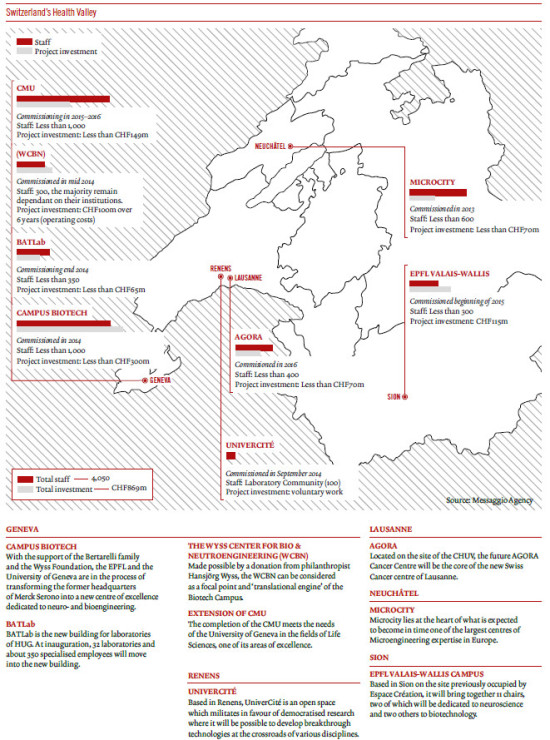

In addition, he is President of BioAlps, a non-profit association that promotes the life sciences cluster of Western Switzerland, notably in biotech and medtech. It has created what is called the Health Valley region, one of the fastest growing life sciences clusters in the world, with more than 750 biotech and medtech companies and 500 research laboratories. It also includes some 20 world-famous research institutions, universities and university hospitals, as well as many bodies supporting innovation such as start-up incubators and venture capital funds.

‘The Campus scientists, researchers and companies will be able to tap into a huge range of specialisms in the region,’ says Dr Dubuis. ‘Neuchatel’s Microcity, for example, is a centre of excellence for the micro-engineering that is essential for many new medtech devices. The region, famous for its watchmaking expertise, can make tiny gadgets that are very reliable over many years.’

Switzerland is an attractive country for such research, he adds: once a poor country lacking natural resources such as minerals, it has developed strengths in creative industries such as engineering and biotech to compensate. It has also welcomed foreigners who can contribute to its economy and even run some of its largest companies.

He says that there is good collaboration between academia and industry in Switzerland, not always the case in many other European countries. ‘It needs a strict framework to define the roles of each partner, but there is much that can be gained from industry – and not just financially. Companies have many competences lacking in higher education, and also terrific knowledge which should be tapped into.’

‘There are two basic principles driving us,’ says Dr Dubuis. ‘The first is innovation: we want to not only innovate, but to innovate in how we innovate – bringing communities together to support innovation. The second is collaboration: we don’t want to compete with any of our partners – we are simply different.

‘We will spend more time understanding diseases. And we will organise ourselves to translate the results of our research into solutions.’