As deleveraging pressures ease and credit conditions improve, conditions should be finally in place for business investment to accelerate in 2016. Today’s GDP release by Eurostat showed euro area investment stagnating in Q3 (0.0% q-o-q), below consensus expectations (+0.2%), following an upwardly revised albeit still modest 0.1% q-o-q increase in Q2. Private investment has failed to boost activity in any meaningful way since the latest leg of the recovery started two years ago. Subdued growth has left Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) close to its early 2013 levels both in absolute terms and as a percentage of GDP. The longer this situation lasts, the higher the risks that under-investment translates into even lower potential growth. Capex underperformance is by no means unusual in the early stages of a recovery, especially in an economy that went through an existential crisis, a massive deleveraging process and a triple-dip in a matter of a few years. At last, we believe that the conditions are finally in place for corporate investment spending to accelerate in 2016, supporting a stronger and broader recovery in domestic demand. Funding conditions have improved further while, more recently, enterprises have signalled their intentions to increase business investment plans.

Topics:

Frederik Ducrozet and Nadia Gharbi considers the following as important: Macroview

This could be interesting, too:

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Big Splits

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Central Bank Halloween

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Widening bottlenecks

Cesar Perez Ruiz writes Weekly View – Debt ceiling deadline postponed

As deleveraging pressures ease and credit conditions improve, conditions should be finally in place for business investment to accelerate in 2016.

Today’s GDP release by Eurostat showed euro area investment stagnating in Q3 (0.0% q-o-q), below consensus expectations (+0.2%), following an upwardly revised albeit still modest 0.1% q-o-q increase in Q2. Private investment has failed to boost activity in any meaningful way since the latest leg of the recovery started two years ago. Subdued growth has left Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) close to its early 2013 levels both in absolute terms and as a percentage of GDP. The longer this situation lasts, the higher the risks that under-investment translates into even lower potential growth.

Capex underperformance is by no means unusual in the early stages of a recovery, especially in an economy that went through an existential crisis, a massive deleveraging process and a triple-dip in a matter of a few years. At last, we believe that the conditions are finally in place for corporate investment spending to accelerate in 2016, supporting a stronger and broader recovery in domestic demand. Funding conditions have improved further while, more recently, enterprises have signalled their intentions to increase business investment plans.

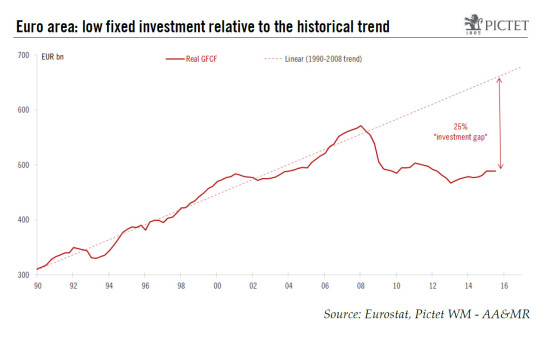

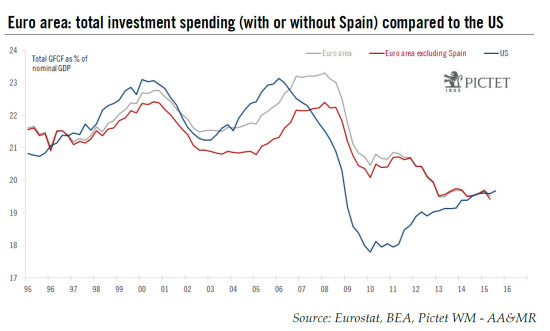

Arguably, the room for investment to catch up looks massive, starting from such a historically low base (see chart below). As deleveraging pressures ease in most euro area member states, we forecast investment spending to expand more rapidly, contributing to at least one-third to overall GDP growth in 2016 and 2017, more than the share of GFCF in GDP (20%) or its average contribution to annual growth prior to the crisis (25%).

Investment: a drag on growth since 2008

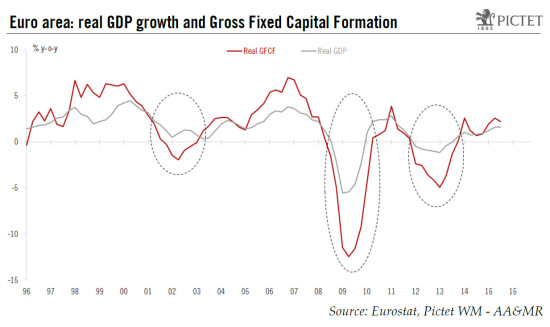

After a recession, investment is often the slowest component of aggregate demand to recover and also the one to contract the most. As illustrated in the chart below, when euro area GDP growth slowed around the turn of the century, investment actually contracted and it did not rebound significantly until 2006. At the heights of the financial crisis, in the spring of 2009, GFCF collapsed by over 12% y-o-y while real GDP contraction was less extreme, at 5.5% y-o-y. The same pattern was visible during the euro area sovereign crisis, when GFCF contracted by 5% y-o-y in Q1 2013 but real GDP fell by ‘only’ 1% y-o-y.

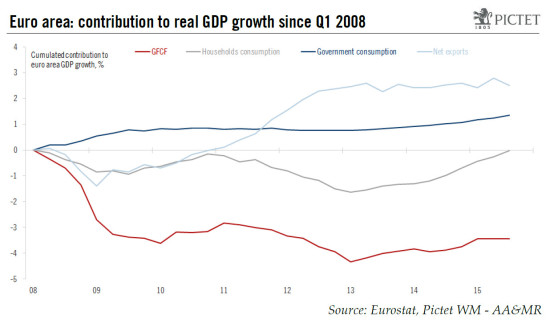

A large part of the euro area’s poor performance since 2008 can be traced back to the weakness in private investment spending. As shown in the chart below, since real GDP reached its pre-crisis peak in Q1 2008, GFCF alone has weighed on GDP growth by around 3.5%. In contrast, net exports have added more than 2% to GDP growth whereas the cumulated contribution from household spending has been broadly flat, albeit increasingly positive in recent quarters.

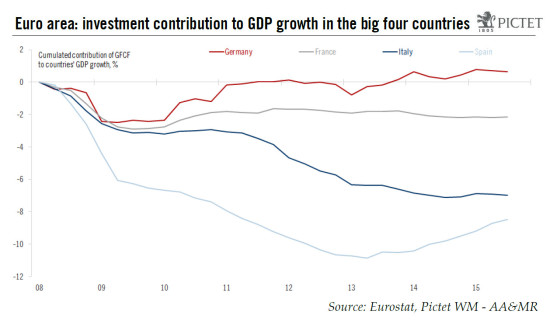

Over the same period and among the four biggest economies, GFCF has contributed positively to GDP growth only in Germany. In Spain, total investment spending seems to have reached an inflection point (as on-going deleveraging in the construction sector is being offset by stronger investment in equipment) whereas in France and in Italy, GFCF continues to weigh on GDP growth, with only tentative signs of improvement.

In general, the most important factors behind the poor performance of investment through this recovery include credit disruptions, the high level of excess capacity, elevated uncertainty and weak aggregate demand. The former factors might also explain why, by international comparisons, the recovery in euro area GFCF has been weaker than in other (over-)leveraged DM economies like the US, for instance, on comparable measures.

Investment in housing less of a drag moving forward

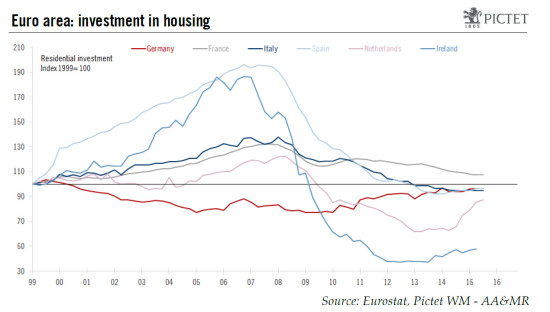

Broad weakness in euro area investment spending masks important differences across countries and sectors. The collapse in a number of national housing markets, in particular, has contributed chiefly to the weakness of total GFCF. Residential investment which accounts for almost a quarter of total fixed capital formation (or, almost 5% of total GDP), began to fall before other sectors of the economy. On aggregate in the euro area, property investment declined by more than 26% from the peak in Q4 2006 to the lowest point in Q2 2014, and has recovered modestly since then, being up by only 2%.

In Spain and Ireland, the countries having experienced the most severe adjustments in housing, investment in dwellings declined by more than 55% and 80%, respectively, since their pre-crisis peak at the beginning of 2007 to their low. Both countries seem to have reached a turning point as investment in housing has increased by 4% and 28% from their low, respectively. In the Netherlands, investment in housing first declined by 50% between Q2 2008 and Q2 2013 but it has risen by 40% since then.

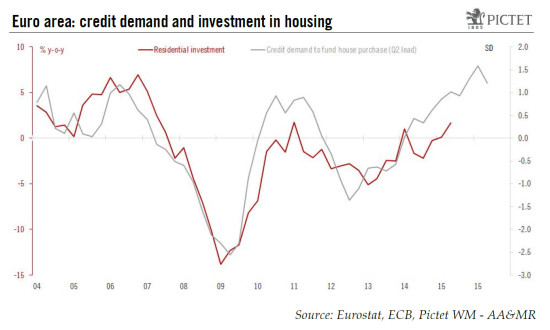

Looking forward, prospects for housing investment look fairly bright. House prices have begun to recover, supported by the gradual improvement in labour market conditions, access to credit as well as more favourable financing conditions. According to the ECB’s Bank Lending Survey, demand for credit for house purchases is projected to increase more significantly in the next couple of quarters (see chart below). Nevertheless, the recovery is likely to remain fragmented across euro area countries. In Spain, investment in the construction sector is likely to remain weak as households complete their deleveraging and inventories remain high.

Conditions have finally been met for euro area investment to become the next engine of growth

Looking at recent trends and forward-leading indicators, there is some ground for reasonable optimism.

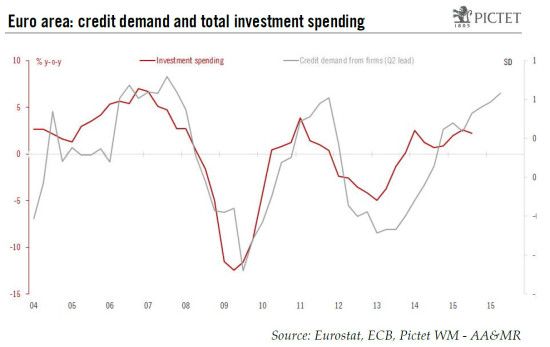

- The credit cycle has turned in 2015, and is expected to support a broader domestic recovery into 2016.

- Internal devaluation and the fall in input (commodity) prices have helped to partly restore corporate margins. Profitability remains weak in aggregate, but it has started to improve on several metrics.

- By the same token, ultra-loose monetary conditions are increasingly translating into lower borrowing costs for private agents as the transmission of the ECB’s monetary stance improves. Crucially, SMEs are finally getting better access to cheaper credit.

- Non-Financial Corporations are signalling their intentions to increase their capex expenditures after years of postponement which have resulted in an ageing of fixed equipment and machinery. According to the ECB’s Bank Lending Survey, one of the factors contributing the most to higher corporate credit demand in Q3 was fixed investment.

- If and when GFCF starts to accelerate, business surveys and excess capacity indicators suggest that investment spending has considerable room to catch up, given the intensity and length of the 2008-2012 slump, if only because of replacement motives.

- The broader euro area fiscal stance will turn slightly accommodative from 2016. Targeted initiatives to support public investment spending may also help at the margin, including at the EU level via the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI).

Looking ahead, our forecasts call for investment to contribute around one third to overall GDP growth of 1.8% for 2016. We believe the risks are tilted towards a stronger expansion in the next couple of years.