Days before the ICIJ released this weekend's trove of "Panama Papers" international tax haven data involving Panamaian law firm Mossack Fonseca, Bloomberg conducted an interview on March 29 with the two founding lawyers. In it, it found that even before the full leak was about to be made semi-public (any of the at least 441 US clients are still to be disclosed), the Panama law firm knew that the game was already largely over. As Bloomberg reports, "during a four-hour interview last week, Mossack and Fonseca sounded like two men in retreat: the go-go days of cranking out shell companies en masse for clients was over; the firm’s been considering scaling back its international franchising; and Mossack was expressing frustration about how Fonseca’s political ambitions were earning them unwelcome scrutiny from regulators and the media. Just days earlier, Fonseca had stepped down as a special adviser to President Juan Carlos Varela, saying he wanted to focus his attention instead on the business." “We are going to make ourselves the right size -- smaller,” Fonseca said. For the co-head of a firm that over the past few decades has helped revolutionize the way companies and wealthy individuals structure their investments across the globe -- and popularized the British Virgin Islands as a hub -- the statement marks a big drop in ambition.

Topics:

Tyler Durden considers the following as important: None, Swiss Banks, Switzerland, Transparency, Volkswagen, Zurich

This could be interesting, too:

Fintechnews Switzerland writes Top 12 Fintech Courses and Certifications in Switzerland in 2025

Claudio Grass writes “Does The West Have Any Hope? What Can We All Do?”

Dirk Niepelt writes “Pricing Liquidity Support: A PLB for Switzerland” (with Cyril Monnet and Remo Taudien), UniBe DP, 2025

Dirk Niepelt writes “Report by the Parliamentary Investigation Committee on the Conduct of the Authorities in the Context of the Emergency Takeover of Credit Suisse”

Days before the ICIJ released this weekend's trove of "Panama Papers" international tax haven data involving Panamaian law firm Mossack Fonseca, Bloomberg conducted an interview on March 29 with the two founding lawyers. In it, it found that even before the full leak was about to be made semi-public (any of the at least 441 US clients are still to be disclosed), the Panama law firm knew that the game was already largely over.

As Bloomberg reports, "during a four-hour interview last week, Mossack and Fonseca sounded like two men in retreat: the go-go days of cranking out shell companies en masse for clients was over; the firm’s been considering scaling back its international franchising; and Mossack was expressing frustration about how Fonseca’s political ambitions were earning them unwelcome scrutiny from regulators and the media. Just days earlier, Fonseca had stepped down as a special adviser to President Juan Carlos Varela, saying he wanted to focus his attention instead on the business."

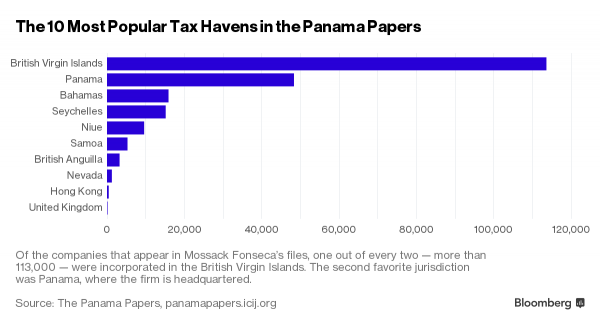

“We are going to make ourselves the right size -- smaller,” Fonseca said. For the co-head of a firm that over the past few decades has helped revolutionize the way companies and wealthy individuals structure their investments across the globe -- and popularized the British Virgin Islands as a hub -- the statement marks a big drop in ambition.

We previously profiled one of the two founders of the infamous law firm. This is what Bloomberg had to add:

Of the two men, it is Mossack, a 68-year-old with German roots, who displays a keen mastery of the nuts and bolts of the business. He did most of the talking during the interview in their Panama City headquarters. The building is sleek, with a distinctive glass-facade, but looks diminutive amid the skyscrapers that dominate the financial district. Across the street is the iconic F&F Tower, a helix-shaped building that helped give the booming city its nickname “Dubai of the Americas.” As the two men spoke that morning, they were flanked by their legal director and two consultants. In all, the firm employs some 500 people in Panama and across the globe.

If Mossack is the nitty-gritty guy, Fonseca, 63, is the self-proclaimed dreamer. He boasts that his friends have labeled him “a da Vinci man” for his interests in politics, law, business, letters and philanthropy. He’s penned a half-dozen novels over the years, and for a while as a young man had considered becoming a priest.

It was during his time as a bureaucrat at the United Nations in Geneva, where he was surrounded by international lawyers, that Fonseca said he was lured by the mysterious world of offshore businesses. “One day it occurred to me that I could do it too,” he said. “I created my little office and left the UN and started with one secretary to create and sell companies.” He’d join up with Mossack soon thereafter.

"It's like selling cars"

Setting up offshore vehicles has become routine for corporations, investment funds, family offices and billionaires. Low- or no-tax jurisdictions offer places to base a company or to send and park cash, company shares, art and other assets. Establishing a structure for them typically costs just a few thousand dollars. Once those fees are handed over to shops like Mossack Fonseca, the organizational and operational framework for the entity is drafted and registered in the local jurisdiction. Annual fees are then charged to maintain the company.

While offshore holdings are usually legal, they can also be used to hide wealth. Since the 2008 financial crisis, Western governments have sought to shed greater light on offshore banking centers, arguing they can be used to avoid taxes or hide illicit funds.

In addressing the legality question, Mossack is fond of drawing an analogy to the auto industry. When you create hundreds of thousands of offshore companies, he says, some are bound to end up in the hands of rotten characters: It’s just the nature of the business and isn’t the fault of the manufacturer. He makes a reference to Volkswagen AG recalling some of its cars before one of the firm’s consultants suggests that isn’t the most appropriate parallel. The scrutiny that the partners are under, Mossack says, stems in part from all the success they’ve had over the years.

However, unlike selling cars, the world is now increasingly focusing on tax evasion as the primary motive behind setting up offshore havens. This is something the Panamanians were clearly aware of with all the heat they had been drawing from independent media inquiries.

The Central American country was already becoming the flag of choice for ship-owners looking to avoid stricter labor and fiscal rules back home when Panamanian officials based their requirements for company incorporation on the laws of Delaware, a U.S. state that protects information on ownership. Panama doesn’t charge foreigners taxes on income earned abroad.

While the Financial Action Task Force recently commended efforts to clamp down on money laundering, the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development calls Panama the "last major holdout that continues to allow funds to be hidden offshore from tax and law enforcement authorities." Panama’s presidential office said in a statement that it has zero tolerance for any legal or financial operations that aren’t managed with the highest levels of transparency.

Whether the new regulations are up to the OECD’s standards or not, the industry is feeling the squeeze, according to Mossack and Fonseca. A law implemented in 2011 required Panama-registered agents to provide client information when requested on all new incorporations, and the British Virgin Islands has adopted restrictions on due diligence.

At this point, the duo admit Panama's prominent reputation as an offshoring center is fast coming to an end. As Mossack admits, "the cat is out of the bag"

It’s a far cry from the boom years, a period when Mossack said he and Fonseca used to keep a vast inventory of “shelf companies” on hand because banks would request as many as a hundred at a time. This weekend’s document leak will only add to the firm’s woes, he said.

"The cat’s out of the bag,” Mossack said. “So now we have to deal with the aftermath.”

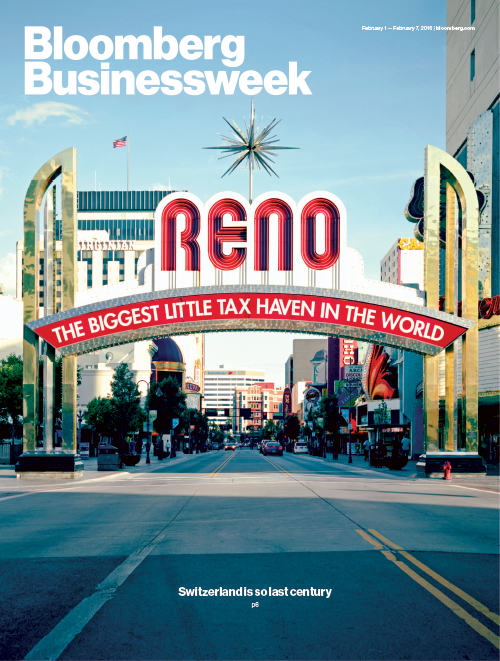

Perhaps it is for Panama. But one place is delighted to take its place: the US, and specifically states like Nevada and Wyoming, which as we showed before, are the new global tax havens.

Recall that according to a recent investigation by Bloomberg, "The World’s Favorite New Tax Haven Is the United States" ...

... and specifically several US states such as Nevada, Wyoming and South Dakota.

After years of lambasting other countries for helping rich Americans hide their money offshore, the U.S. is emerging as a leading tax and secrecy haven for rich foreigners. By resisting new global disclosure standards, the U.S. is creating a hot new market, becoming the go-to place to stash foreign wealth. Everyone from London lawyers to Swiss trust companies is getting in on the act, helping the world’s rich move accounts from places like the Bahamas and the British Virgin Islands to Nevada, Wyoming, and South Dakota.

“How ironic—no, how perverse—that the USA, which has been so sanctimonious in its condemnation of Swiss banks, has become the banking secrecy jurisdiction du jour,” wrote Peter A. Cotorceanu, a lawyer at Anaford AG, a Zurich law firm, in a recent legal journal. “That ‘giant sucking sound’ you hear? It is the sound of money rushing to the USA.”

That money is rushing for one simple reason: dirty foreign - and local - money is welcome in the U.S., no questions asked, to be shielded by the most impenetrable tax secrecy available anywhere on the planet.

One may even say that nowadays, US-based tax havens are the new Switzerland, or Bahamas or, for that matter, Panama. Indeed, for most Americans, offshore tax haven are now meaningless with the passage of the FATCA law, which makes the parking of dirty US money abroad practically impossible. So where does that money go instead - it stays in the US:

Others are also jumping in: Geneva-based Cisa Trust Co. SA, which advises wealthy Latin Americans, is applying to open in Pierre, S.D., to “serve the needs of our foreign clients,” said John J. Ryan Jr., Cisa’s president.

Trident Trust Co., one of the world’s biggest providers of offshore trusts, moved dozens of accounts out of Switzerland, Grand Cayman, and other locales and into Sioux Falls, S.D., in December, ahead of a Jan. 1 disclosure deadline.

“Cayman was slammed in December, closing things that people were withdrawing,” said Alice Rokahr, the president of Trident in South Dakota, one of several states promoting low taxes and confidentiality in their trust laws. “I was surprised at how many were coming across that were formerly Swiss bank accounts, but they want out of Switzerland.”

And, to top it off, there is one specific firm which is spearheading the conversion of the U.S. into Panama: Rothschild.

Rothschild, the centuries-old European financial institution, has opened a trust company in Reno, Nev., a few blocks from the Harrah’s and Eldorado casinos. It is now moving the fortunes of wealthy foreign clients out of offshore havens such as Bermuda, subject to the new international disclosure requirements, and into Rothschild-run trusts in Nevada, which are exempt.

* * *

For financial advisers, the current state of play is simply a good business opportunity. In a draft of his San Francisco presentation, Rothschild’s Penney wrote that the U.S. “is effectively the biggest tax haven in the world.” The U.S., he added in language later excised from his prepared remarks, lacks “the resources to enforce foreign tax laws and has little appetite to do so.”

Yes, Mossack Fonseca may now be history, and its countless uberwealthy clients exposed, but none other than Rothschild is now delighted to be able to fill its rather large shoes.

In fact, someone with a conspiratorial bent may decide that the dramatic takedown of the Panama "tax offshoring" industry was nothing more than a hit designed to crush the competition of US-based "tax haven" providers... such as Rothschild.