The West is getting increasingly worried about China’s export prowess as its companies are rapidly gaining market shares in green and high-tech industries. Recently, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen accused China of industrial overcapacity and urged Europeans to respond jointly to the latter’s nonmarket practices. Allegedly, China is flooding international markets with cheap products of good quality primarily due to industrial subsidies. The U.S. and its allies are ramping up protectionist measures such as punitive tariffs, technology controls and a reinforcement of their own industrial policies. What if they are wrong and China is just providing better incentives to work, save and invest?Is overcapacity boosting China’s EV exports?Sales of Chinese electric

Topics:

Mihai Macovei considers the following as important: 6b) Mises.org, Featured, newsletter

This could be interesting, too:

RIA Team writes The Importance of Emergency Funds in Retirement Planning

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Gesetzesvorschlag in Arizona: Wird Bitcoin bald zur Staatsreserve?

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes So bewegen sich Bitcoin & Co. heute

Nachrichten Ticker - www.finanzen.ch writes Aktueller Marktbericht zu Bitcoin & Co.

The West is getting increasingly worried about China’s export prowess as its companies are rapidly gaining market shares in green and high-tech industries. Recently, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen accused China of industrial overcapacity and urged Europeans to respond jointly to the latter’s nonmarket practices. Allegedly, China is flooding international markets with cheap products of good quality primarily due to industrial subsidies. The U.S. and its allies are ramping up protectionist measures such as punitive tariffs, technology controls and a reinforcement of their own industrial policies. What if they are wrong and China is just providing better incentives to work, save and invest?

Is overcapacity boosting China’s EV exports?

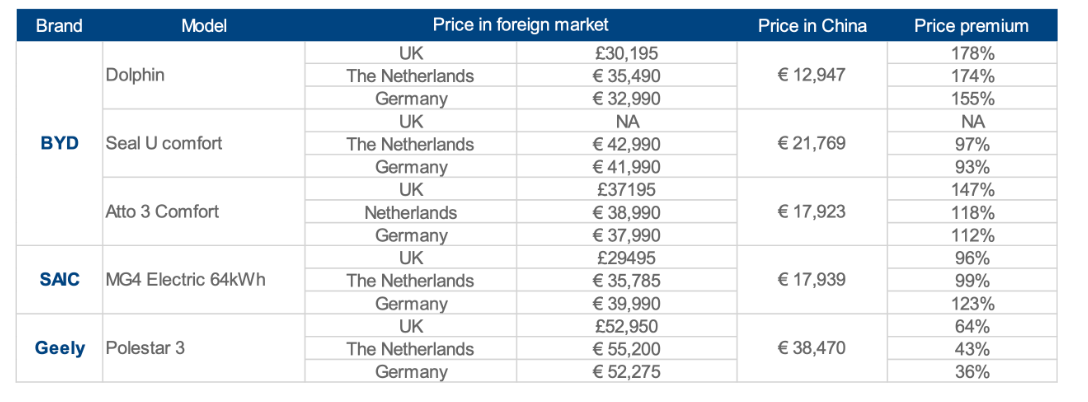

Sales of Chinese electric vehicles in Europe soared to around 20% of the market in 2023 and are set to reach about one-quarter in 2024. Both the U.S. and EU slapped China’s EV exports with high tariffs, blaming China of industrial overcapacity. If true, this would mean that Chinese producers use dumping prices to sell excess output abroad. But this is not the case, as the price of an electric car has been about half in China than in the U.S. and Europe in 2023. Actually, Chinese EVs sell at vast price premiums on Western markets (Table 1) and are likely to enjoy healthy profit margins even after the new tariffs are introduced.

Table 1: EV models prices in selected markets

Source: EVMarketsReports.com.

It is also claimed that overcapacity in China’s EV sector has been unfairly fueled by industrial policy and generous subsidies. Analysts criticize China’s purchase subsidies (approved buyer’s rebate and sales tax exemption), but the U.S. and the EU have been more generous than China. Average EV purchase subsidies in China gradually decreased from about 2,300 euros to 1,300 euros between 2010 and 2022 and were eliminated in 2023. Total average support per vehicle has decreased to about $4,600 in 2023, which is less than the U.S. federal tax credit of $7,500 and incentives in European countries.

As a first mover, China has spent about $230 billion to boost the EV sector so far, according to analysts for the Center for Strategic and International Studies. However, China is phasing out subsidies, which declined substantially from over 40% of total sales to only 11.5% in 2023. At the same time, in order to catch up, the U.S. is planning to further ramp up its aid to the EV sector by an estimated $174 billion under the Inflation Reduction Act. Eventually, total Inflation Reduction Act subsidies could end up three times higher, with tax credits for EVs of up to $390 billion and direct subsidies of $130 billion. However, while China’s EV subsidies are constantly brought into the limelight, the Western ones are swept under the carpet.

How significant are industrial subsidies?

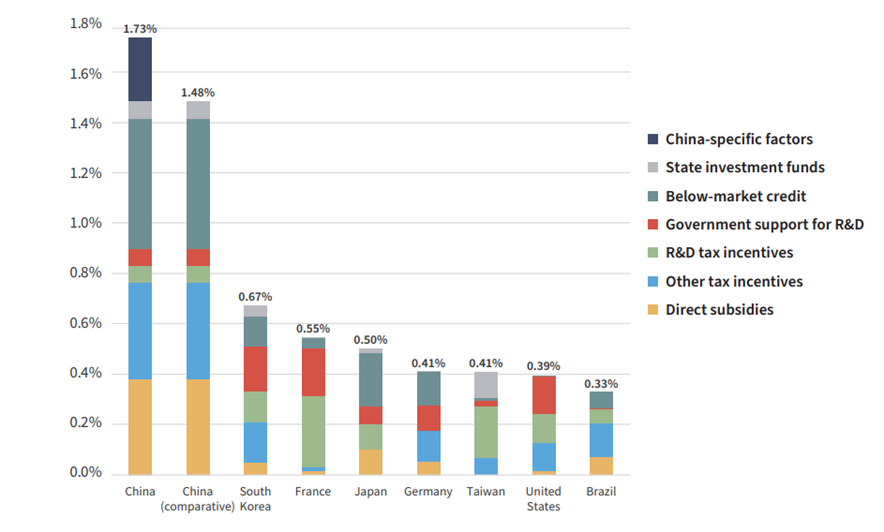

The same goes regarding public support for the entire industrial activity. A widely quoted CSIS study estimates China’s subsidies at about $248 billion or 1.7% of the gross domestic product in 2019, which is two to three times more than in key economies (Figure 1). Yet in nominal terms, subsidies of $84 billion (0.4% of GDP) are not trivial in the U.S. either. At $262 billion (1.7% of GDP) in the EU as a whole, industrial subsidies are almost at the same level as in China.

Figure 1: Industrial policy spending in key economies, 2019

Source: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

According to the CSIS study, the majority of aid instruments in China (direct subsidies and below-market credit) go to state-owned enterprises. Yet state-owned enterprises account for only about 10% of exports, which means that the direct contribution of industrial subsidies to China’s competitiveness is not the key determinant. Mainstream pundits seem to exaggerate both the size and role of Chinese subsidies in order to argue for more industrial policy in the West. Indeed, industrial policy is in fashion again worldwide, with a steep increase in industrial policy interventions in recent years. High-income countries, having more fiscal resources, are at the forefront of this trend. The Biden administration launched several onerous programs exceeding $2 trillion to revive green and high-tech manufacturing. In Europe, Mario Draghi wants to place more public investment and an EU “Industrial Deal” at the core of revitalizing productivity growth.

Is industrial policy the right move?

There are strong arguments against industrial policy such as the lack of market knowledge by bureaucratic decision-makers, the capture of decisions by special interest groups, and high seen and unseen costs, together with an underwhelming historical experience riddled with failures. However, these are now brushed aside, with claims that previous industrial policies were not well-targeted. China is being advertised as the “true example” of industrial policy, without a proper understanding of its specificities.

According to García-Herrero and Schindowski, China’s industrial policy differs from that of a market economy due to significant government interventions through the state-owned enterprises sector. Private companies have traditionally been disadvantaged relative to state-owned enterprises through arbitrary fees, fines and extortion as well as more expensive credit. Industrial policy is primarily a tool to alleviate this disadvantage and directs private capital to the government’s strategic objectives. Moreover, industrial policy has not benefited productivity growth as it fosters cronyism and pervasive ties between government officials and large enterprises to the detriment of more productive but not politically connected small and midsized enterprises. Other papers also emphasize that China’s experience with industrial policy is mixed at best, while massive state subsidies led to numerous failures.

At the same time, China manages to dominate not only the nascent global EV market, but the entire global clean tech manufacturing sector, including wind turbines, solar panels and car batteries. All these sectors have recently been under scrutiny for price dumping and subsidies, joining more traditional ones such as steel, aluminum and shipbuilding. According to recent research, China holds a dominant position for almost 600 products out of 5,000 in the global export markets, mainly in electronics, textiles/clothing, footwear and machinery. This is unparalleled by any other country. Once acquired, the dominant positions persisted over time, meaning that the industries remained highly competitive even after subsidies were discontinued. It is obvious that more fundamental factors are at play, rather than a huge scheme of industrial policy cross-subsidization as argued by mainstream pundits. With the share of labor compensation in GDP at about the same level as in the U.S., the case for social dumping appears feeble too.

Low taxes and fast capital accumulation are key

China has had an impressive economic performance since the acceleration of market-oriented reforms and World Trade Organization accession in 2001. Its economy accounts for a third of the global gross manufacturing production today, from less than 10% in 2003, and dominates numerous advanced technology sectors. This was possible due to rapid capital accumulation fueled by very high savings and investment ratios, the latter exceeding 40% of GDP for about two decades (compared to 25% of the GDP global average).

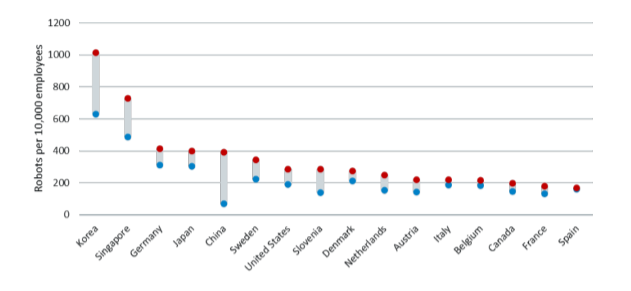

Some investments were potentially misallocated by the large state-owned enterprises sector, by industrial policy failures or in the real estate bubble. Yet the productive ones were sufficient to ensure a notable increase in the capital stock as reflected by the surge in automation and robot density, with China catching up with the U.S., Japan and Germany (Figure 2). Together with steady progress in innovation, where China has surpassed Japan and is gradually closing the gap with the EU, these investments reinforce high productivity growth and cheap exports of manufactured goods.

Figure 2: Robot density in 2016 and 2022

Source: International Federation of Robots.

This is primarily the result of a limited welfare state, with China allocating about 8% of GDP to social spending, a fraction of the level in the U.S. (20%) and Germany (25%). Although China has eradicated extreme poverty, it does not try to soak the rich and the middle class through high-income redistribution. Unlike in the West, the low tax burden and limited progressivity in its tax system encourage strong labor force participation, long working hours and high savings. The Chinese work around 2,170 hours on average per year (about 25% more than in the U.S. and 50% than in Germany).

Overall, China redistributes only about 28% of GDP in total government spending relative to a bloated 42% on average in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries and close to 50% of GDP in Western Europe. This explains China’s economic success and not the meager 0.5-1% of GDP it may spend more on industrial policy with doubtful results. Western economies have developed a predilection for the progressive taxation of incomes, penalizing the most entrepreneurial and hardworking members of society, reducing work incentives, and discouraging savings and investment. Even when industrial subsidies are lavishly provided, such as for the nascent car batteries sector, domestic producers still cannot compete with more nimble Asian competitors.

In conclusion, the industrial policy argument is just a smoke screen by socialist economists to cover up inefficiencies of the much-larger government redistribution in the West. The latter is used to subsidize not only companies, but also individuals, through a huge welfare system and broad range of public services. Even worse, a large chunk of public spending is financed by mounting debt and the printing press. Replicating China’s industrial policies will not help solve this huge problem but can even worsen it.

Tags: Featured,newsletter